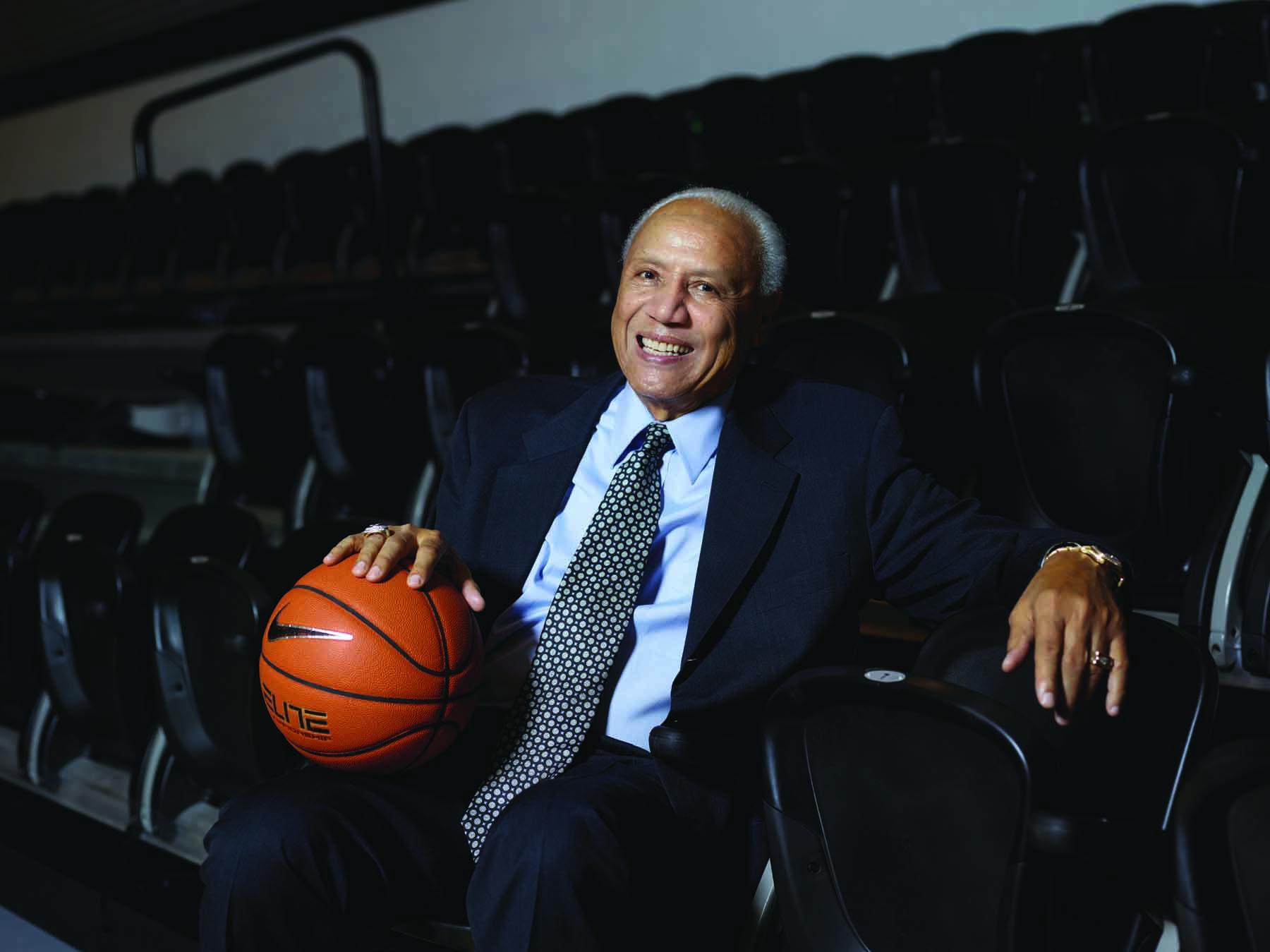

Champion at Life: Basketball star Lenny Wilkens ’60

Remembering Lenny Wilkens ’60, ’80Hon.

Providence College mourns the passing of one of its most distinguished alumni, Lenny Wilkens ’60 and ’80Hon., whose legacy as a basketball legend and humanitarian has left an indelible mark on our community. As a two-time All-American, Lenny led the Friars to national prominence and went on to become one of the most respected figures in NBA history — a Hall of Famer as both player and coach, and a champion on and off the court. His grace, leadership, and commitment to service embodied the very best of our values at Providence College. We extend our deepest condolences to his wife Marilyn, their children, and loved ones. May he rest in peace.

COLLEGE PRESIDENT REV. KENNETH R. Sicard, O.P. ’78, ’82G

Basketball royalty

This podcast was recorded in April 2023.

Champion at life: Basketball star Lenny Wilkens

This story was published in the Fall 2016 issue of Providence College Magazine.

By Vicki-Ann Downing

Lenny Wilkens ’60, ’80Hon., the man who would become Providence College’s first basketball superstar, arrived quietly on campus in the fall of 1956, nine months after Alumni Hall opened with a gymnasium built with basketball in mind.

No one expected much from the slim, left-handed guard who stood just over 6 feet tall. His athletic career was made possible because someone decided to help — a distinction he has never forgotten.

When Wilkens was about to graduate from Boys High School in Brooklyn, N.Y., his parish priest, Rev. Thomas Mannion, wrote to PC’s athletic director, Rev. Aloysius Begley, O.P. ’31, asking that Wilkens be considered for a scholarship. PC’s head coach, Joe Mullaney ’65Hon., ’98Hon., met Wilkens in New York. But the invitation to play for the Friars didn’t come until after Mullaney’s father watched Wilkens play in a summer tournament on Long Island.

From the time he arrived on campus, Wilkens made his mark. His freshman team won all 26 games and easily defeated the varsity. When he was a sophomore, the Friars went 18-6. His junior year brought PC’s first 20-win season and its first invitation to the NIT, the National Invitation Tournament, at Madison Square Garden in New York City. One of a dozen teams selected for the premier college event, the Friars made it to the semifinal round, the equivalent of the NCAA Final Four.

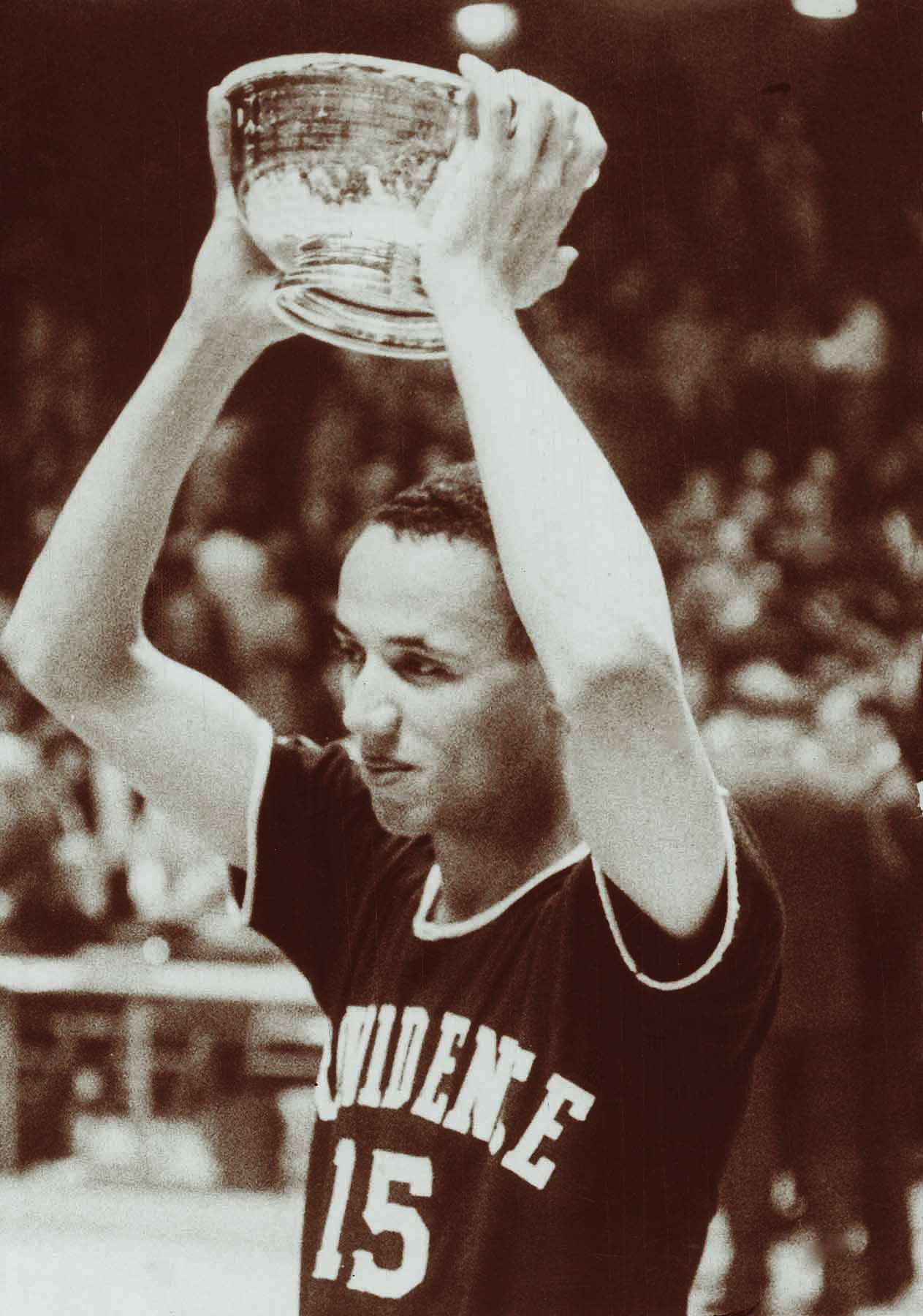

As senior co-captain in January 1960, with 20th-ranked St. Joseph’s leading the Friars by 3 with just over a minute to play, Wilkens stole the ball on three consecutive possessions and scored twice in a 64-63 win that pushed PC into the Top 20 for the first time. In the NIT that year, the Friars made it all the way to the final. Wilkens was the tournament MVP despite their loss. He then became the first Friar selected for the East-West All-Star Game, featuring the best college seniors in the country. With his team down by a point, Wilkens stole the ball, sank the winning shot for the East, and was named tournament co-MVP.

How different were professional sports then? Wilkens was a first-round draft pick, selected sixth overall by the Saint Louis Hawks, then one of only eight NBA teams. He learned about his selection when the PC athletics office called to tell him. Since he’d never seen a professional basketball game before, he asked a visiting scout for the New York Knicks to get him some tickets.

Wilkens studied the Hawks as they played the Boston Celtics in the playoffs at Boston Garden.

“I thought I was as good as the Hawks’ guards,” said Wilkens. “I decided to sign with them. You’re young and you’re confident. You say, ‘I think I can do this.’”

He sure could. Wilkens is the only person inducted into the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame three times — as a player in 1989, as a coach in 1998, and as an assistant coach of the 1992 Olympic gold-medal USA “Dream Team” in 2010. He won another gold medal as head coach in 1996. He coached the Seattle SuperSonics (including former Friar guard Joe Hassett ’77) to the NBA title in 1979.

In 1995, Wilkens broke Red Auerbach’s record of 938 career wins as a professional coach and established his own — 1,332 — which stood until Don Nelson broke it in 2010. The NBA named Wilkens to its list of the 50 greatest players of all time and the top 10 coaches of all time. He was a 13-time all-star as a player and a coach in a career that lasted more than 40 years.

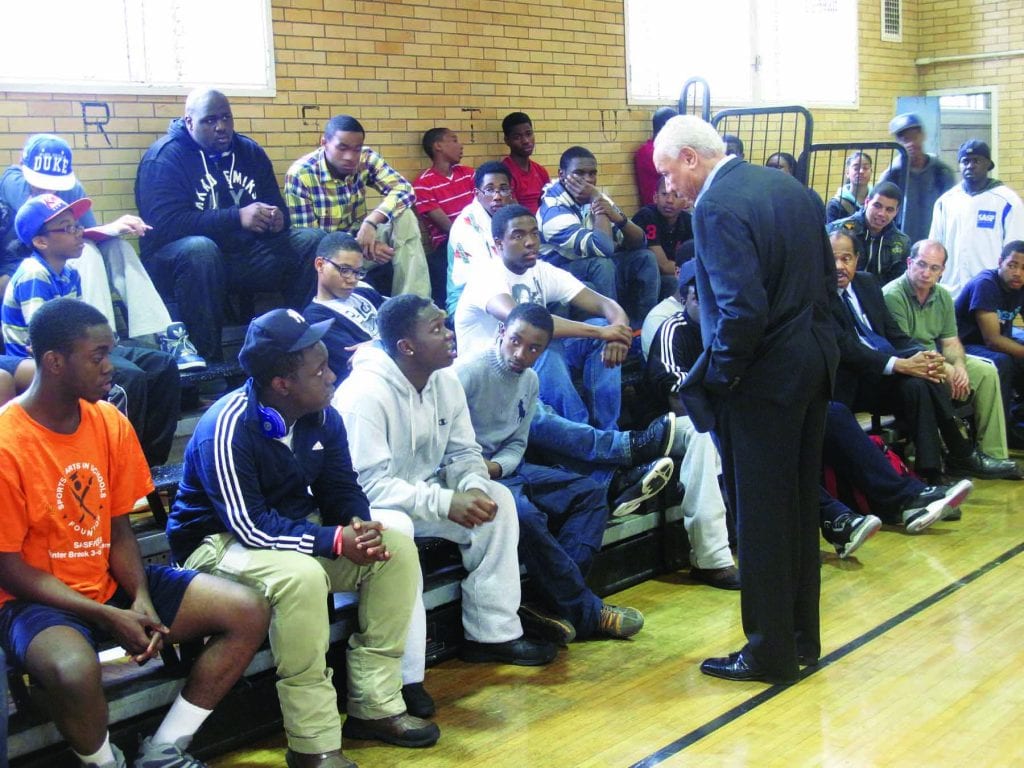

His impact extends beyond basketball. The Lenny Wilkens Foundation, which he established in 1971 with his wife, Marilyn, has raised nearly $8 million to support organizations that help needy children in the Pacific Northwest. Its main beneficiary is the Odessa Brown Clinic, which provides medical and dental care for children in Seattle. Each July, the foundation hosts its major fundraiser, a Celebrity Weekend that draws 700 people for a dinner, auction, and golf tournament. Wilkens’ Friar teammates, Johnny Egan ’61 and Tim Moynahan ’61, regularly attend.

Wilkens never misses an opportunity to talk to the youngsters served by the clinic.

“I want the kids to see me and to know they can be successful,” he said.

Wilkens met Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr., in Birmingham, Ala. He met Nelson Mandela and Desmond Tutu during a visit to South Africa. He’s chatted with Jimmy Carter and both Presidents Bush. He hosted a reception for Barack Obama in his lakefront home in Seattle. He even met a tiny Stephen Curry when coaching his father, Dell Curry, with the Cleveland Cavaliers.

Wilkens is known for his self-effacing manner and his generosity — traits that do not win basketball games. There is a fire inside him, and he will tell you that it comes from his mother, Henrietta. She was a white, Irish-Catholic woman left to raise five children on her own when his father, Leonard Randolph Wilkens Sr., who was Black and worked as a chauffeur, died of complications of a bleeding ulcer.

Wilkens was 5 years old then, the oldest son.

“I remember a nun holding me at the wake and saying, ‘You’re the man of the family now,’” said Wilkens.

“When my mother would take us shopping, we were the color of the rainbow,” he said. “People would look. She would turn around and ask them what they were looking at.”

Her courage was fueled by her faith, Wilkens said.

“My mother was what we call a daily communicant,” he said. “She went to Mass every day. She prayed every novena. She prayed more than anybody I knew. She would tell me, ‘You have to be accountable. Let honesty and integrity define your character.’”

Because of his mother, Wilkens was an altar server at Holy Rosary Church in the days of the Latin Mass, and the parish priest, Father Mannion, looked out for him.

“Whenever I got angry about things, Father Mannion would say, ‘Who promised you? Did someone promise you it was going to be easy?’” Wilkens remembered. “He’s right, no one promises you anything. You want it to be better, you have to speak up.”

Growing up in Bedford-Stuyvesant, Wilkens played stickball, kickball, and baseball, and cheered for Jackie Robinson and the Dodgers at Ebbets Field. Basketball was secondary. He was good enough to make the high school team as a freshman, but since he wasn’t going to get much playing time, he quit to work in a grocery store to support his family. He played CYO ball instead and sharpened his skills on the Brooklyn playgrounds, where competition was fierce.

His friend Tommy Davis, a high school All-American in baseball and basketball who later played with the Los Angeles Dodgers, convinced him to try out for the high school basketball team again as a senior. This time, Wilkens made the starting five.

“I think there are people in the world that influence you,” Wilkens said. “In my life, I got to see people who were all about helping people, about trying to make it better.”

One of them was Ralph A. Pari ’50. Wilkens met Pari, a Friars fan, in the Alumni Hall cafeteria after a game, and Pari invited Wilkens to join him in Smithfield, R.I., for dinner with his wife, Violet.

It was the beginning of a lifelong friendship.

“They treated me like a son,” said Wilkens.

Studying economics at PC, he wanted his professors to know he was a serious student.

“Most of my professors would tell you I wasn’t afraid to question them on whatever they were teaching,” Wilkens said.

He remembers the Dominicans who taught and supported him: Rev. Cornelius P. Forster, O.P.; Rev. Thomas H. McBrien, O.P.; Rev. Raymond B. St. George, O.P. ’50; and Rev. Robert A. Morris, O.P. ’46, ’82Hon. Wilkens visited Father Morris regularly until his death last year. In 1962, when Wilkens married in New York, six Dominicans were at his wedding.

Wilkens was one of the few Black students on campus then. For a time, he had a white girlfriend. Her father did not approve of their relationship. One day Wilkens was called to meet with the dean of students. His girlfriend’s parish priest was there and told Wilkens that their association was inappropriate.

“When he was done, I just looked at him and said, ‘You are supposed to be a man of God. I’m shocked. We’re just friends,’” said Wilkens. “And I got up and walked out.”

When Wilkens arrived in St. Louis to play basketball, Blacks were not allowed to eat in certain downtown restaurants. There were only a few Black players on every NBA team. He got some hate mail, and when he bought a house in the suburbs, “For Sale” signs went up.

“Some came down when they realized we weren’t going to set fire to the place,” said Wilkens.

Sports has done a lot to improve the racial climate in the country, he said. Black athletes have broken barriers.

“I always feel people have to get to know you,” said Wilkens. “I can feel. I can think. I’ve had experiences that are the same as your experiences.”

The NBA was a different world in 1960.

“The temptations were always there, but there were only eight teams,” said Wilkens. “There were not that many opportunities to play. You had better take advantage.”

Salaries were low, and players were expected to work during the offseason. Some teams offered medical insurance, others did not. The per diem rate for travel was just $8. Players were reluctant to serve in the Players Association, fearing they would be traded.

Wilkens stepped up and became player representative for the Hawks. In 1964, he was part of a group that threatened to strike the NBA All-Star Game in Boston — which would have meant a loss of national television coverage for the league. The owners gave in and agreed to have a pension in place for players. Later, as president of the Coaches Association for 17 years, Wilkens helped negotiate a pension for coaches, too.

“Trying to make things better,” he said.

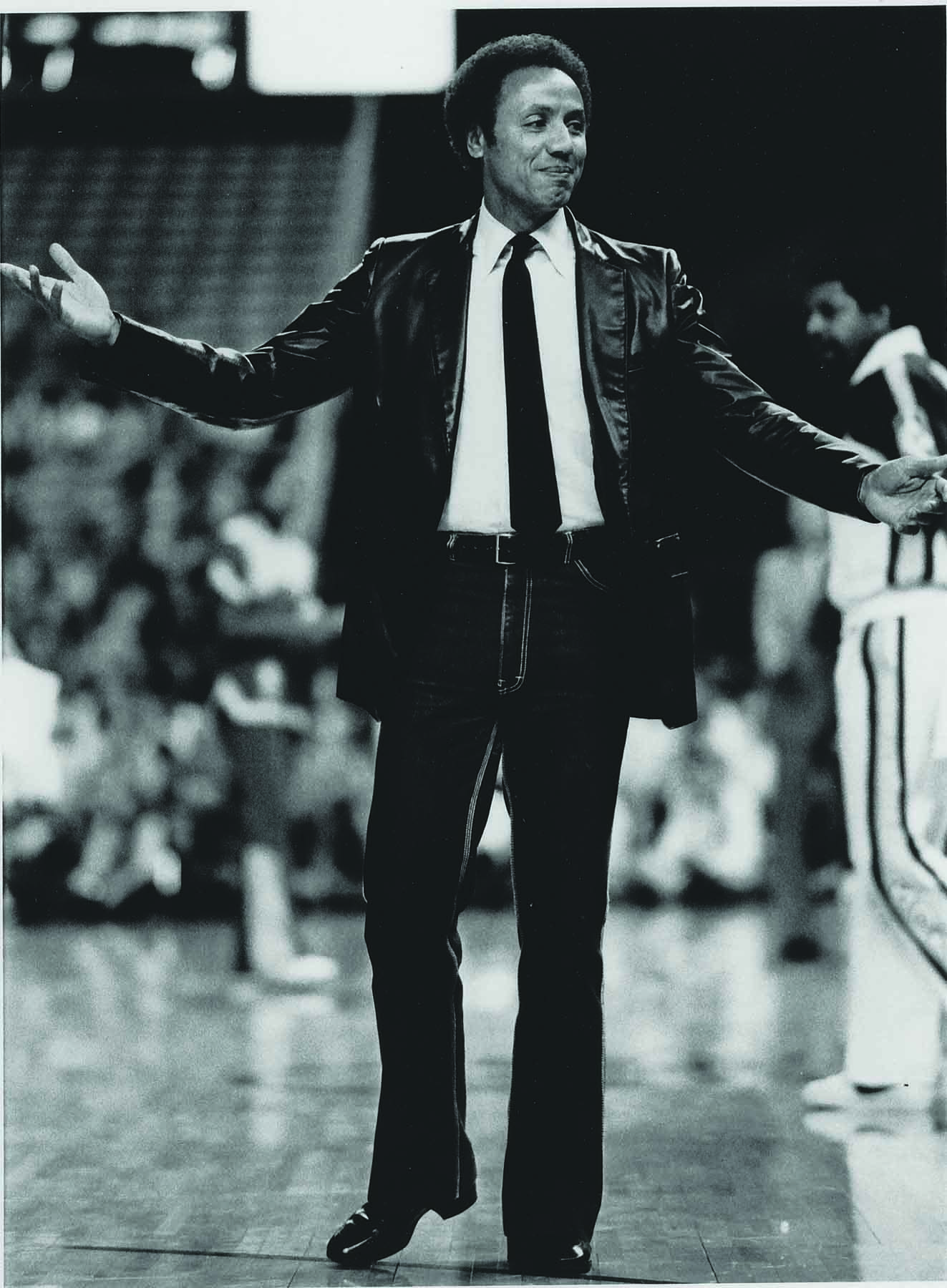

When the Hawks were sold to Atlanta, Wilkens was traded to Seattle. In 1968, after just a season, he was asked to be player-coach.

“I said, ‘You’re crazy,’” said Wilkens. “They said, ‘You run the team on the floor anyway.’”

Coaching was a challenge. Wilkens learned by observing “guys who were very good.” He invited Marv Harshman, coach at the University of Washington, to a practice. Harshman told him, “You have to show them, and you can’t be nice about it, either.”

Wilkens also drew on his military service. He served 18 months of active duty in the Army as an executive officer to a military commander and was in charge of training troops. ROTC was required during his freshman and sophomore years at PC, but he chose to continue the program through graduation.

“Once I was coach, I didn’t eat or hang out with the guys anymore,” said Wilkens. “You had to set a precedent and let the players know that this is the way it’s going to be.”

One day in 1971, two women in Seattle — “movers and shakers in the community,” Wilkens said — “got my wife to convince me to have lunch with them.”

The women ran the Odessa Brown Clinic, which provided free health care for children. A pediatrician saw patients several days a week on a volunteer basis. Wilkens was impressed. He established his foundation soon after. It benefits the clinic and other organizations, including Make A Wish, the Boys and Girls Clubs, and the Center for Children and Youth Justice.

Today, Seattle is his home for good. Its climate suits him — he doesn’t like hot weather. Though he sometimes works out on a treadmill, his exercise room has become a playroom for his seven grandchildren. His daughters, Leesha and Jamee, live nearby with their families, but son Randy and his family are in Atlanta, and when Wilkens and his wife travel, it is to see them.

The grandchildren “are lots of fun. They’re active,” said Wilkens.

“Randy has our only grandson. He plays soccer and basketball. He’s 7. When I watch games, he’ll come and sit on my lap.”