Learning to plant seeds in Guatemala

Story and Photos by Michael Hagan ’15

By the time 12 Providence College students arrived at the San Lucas Tolimán Mission on the shore of Guatemala’s Lake Atitlán, they had learned to brace for the unexpected.

Just getting there was an adventure complete with weather cancellations, power outages, and travel through the night via two flights and two three-hour drives. But even the predeparture wind storm and mile-high elevation in San Lucas were lesser shocks than the readings assigned over nearly two months of study and preparation for the trip.

The students were members of THL 375: Global Service in Solidarity, a course inspired by revisions to the core curriculum several years ago and which was being taught for the first time by Dr. Dana Dillon, associate professor of theology. The course promised to introduce students to Christian social principles through study and an international service-learning trip over spring break, and it attracted students from a range of academic disciplines. Its members enrolled sharing variations of a common notion about mission work — that they would, as one reading described, be “bringing light and returning to tell the story.” By Dillon’s design, expectations were dashed.

“Many short-term service trips can leave impressions that a week of service can radically change the world. I designed this course to complicate those impressions,” said Dillon.

To students, course texts seemed to condemn the mission trip they were preparing to take. “I worried that as short-term visitors, our trip would end up more vacation than service,” said Luke Jenness ’19 (Shelton, Conn.). “Reading about Guatemala’s history and the damaging effects of tourism in the developing world left me uncomfortable about what we were doing.”

Even those already aware of the problematic aspects of short-term mission work were caught off-guard.

“I came into class thinking that by being aware of this crosscultural dilemma I was free from the ‘white savior’ mentality, and man was I wrong,” said Kate Corwin ’19 (South Orange, N.J.). “There is still so much to learn.” Some students were discouraged. Some were angry. All had the jarring title of one reading stamped on their minds — “To Hell with Good Intentions.”

So it was with a peculiar mix of excitement and angst that the students, their instructor, and I landed in Guatemala City and set out on winding mountain roads to San Lucas Tolimán.

San Lucas Tolimán is a remote village inhabited mostly by highland Maya. Centuries under an unjust plantation system impoverished its residents, and decades of civil war that followed a 1954 U.S.-backed coup d’etat ravaged the already underdeveloped region. The late Rev. Greg Schaffer of the Roman Catholic Diocese of New Ulm, Minn., was dispatched by his bishop in 1963 to serve as a parish priest in San Lucas. He and dozens of other young missionary priests were the American Church’s answer to Pope St. John XXIII’s call to address a dire clergy shortage in Latin America. Father Greg did not anticipate his assignment, much less that he would remain for nearly 50 years.

It became clear to Father Greg upon arrival that his role would be different in Guatemala than in Minnesota. Ministering to the needs of his new flock would necessarily involve initiatives to relieve poverty and develop the local economy. Father Greg knew that the desired shape of that growth could only be discerned through careful listening. As he came to understand his new neighbors’ priorities, he began the work of connecting local initiative with outside resources and expertise.

Today, the mission’s priorities remain largely the same, though tremendous progress has been made. The mission oversees numerous facilities including a school, medical clinic, women’s center, and coffee roasting facility, along with ongoing construction and infrastructural projects. Numbers tell a story of astounding impact. By the time of Father Greg’s death, the mission helped 3,700 families acquire three-acre plots of land. Since the founding of the mission school, literacy has increased from 2.5% to 85%. But the success and longevity of the mission and its work hinge on an operational model in which local initiative to address both the immediate pain and root causes of poverty is aided — not directed — by foreign resources. In keeping with the Catholic principle of subsidiarity, the mission’s projects belong to the village.

“We do not come to help, but to learn and walk with the people of San Lucas,” Friends of San Lucas explains in its information for volunteers.

And while the group did move several tons of earth and clear flammable brush, among other tasks, at project sites around San Lucas, the heart of the trip really did consist of learning and walking. We learned about the achievements of the people of San Lucas in partnership with Father Greg. We awoke before dawn to walk up what felt like the full height of a mountain (only to realize we were barely halfway to the summit). We learned on that walk and from that vantage point why the land is called “Guatemala” — indigenous for “land of the trees.” We walked alongside workers carrying out the mission’s many projects, offering extra hands and learning to use their tools and processes as we worked.

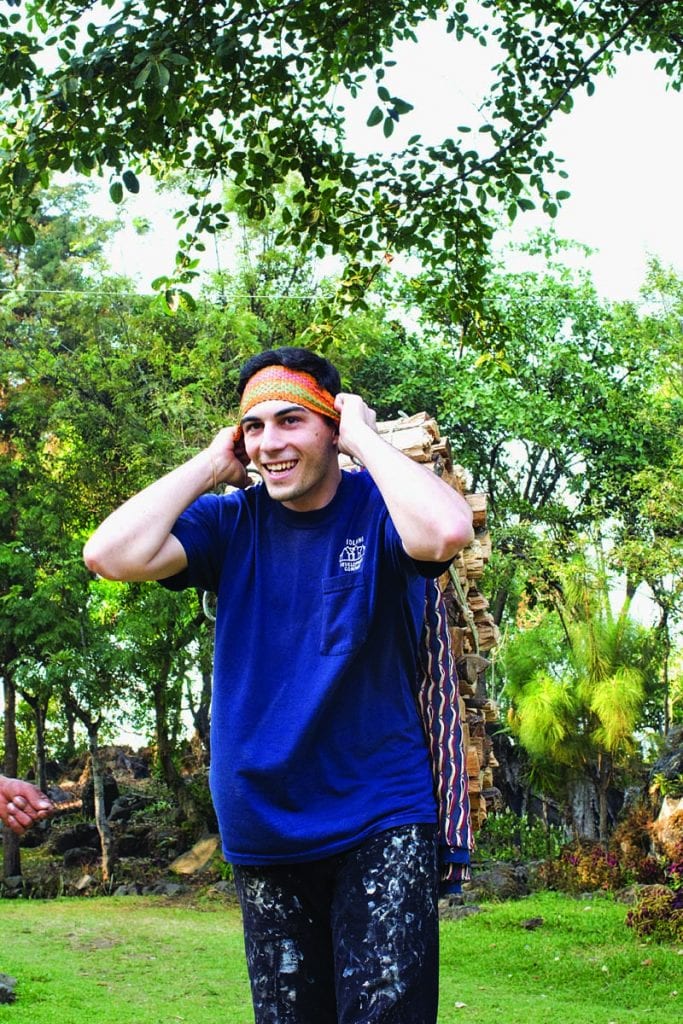

We spent an afternoon learning and practicing daily tasks of life in the mountains. Our hosts laughed with us as we struggled to balance baskets on our heads, carry logs on our backs, and make tortillas by hand. We learned about innovative cement stoves engineered to preserve traditional cooking methods while protecting families from harmful fumes. Having packed lightly, we were relieved by the chance to hand-wash clothes at a communal laundry facility that offers residents a safer and more convenient option than the lake.

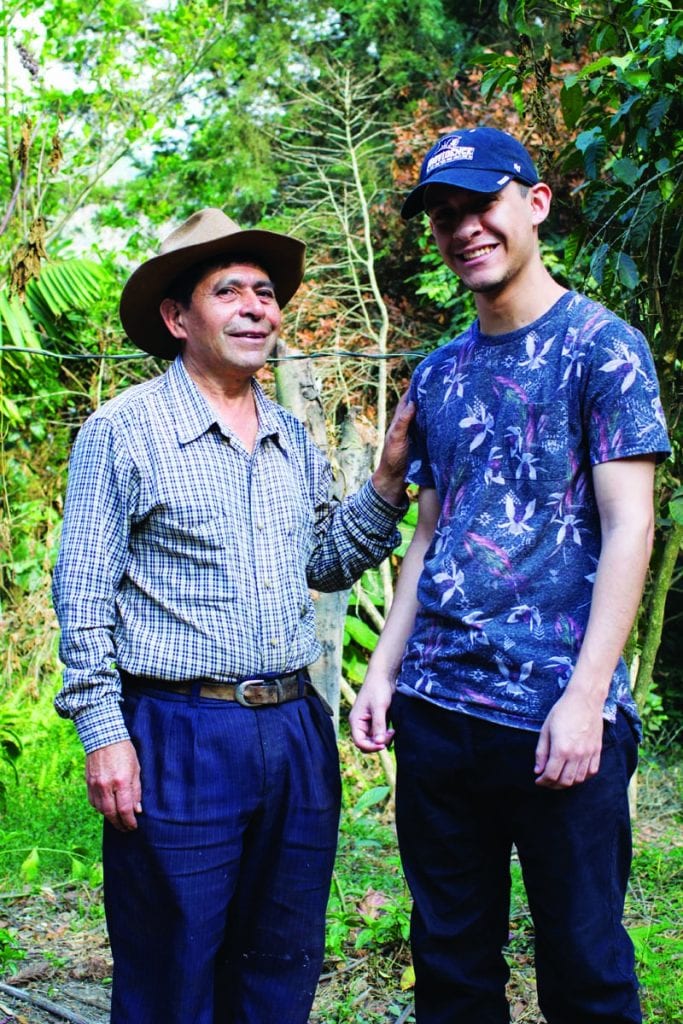

Students were particularly inspired by Toribio, the manager of San Lucas’ reforestation project. A tactic of the state during the civil war was to set fire to mountainsides where guerillas were suspected of hiding. The fires devastated communities in the mountains, and the loss of vegetation has since made landslides deadlier and more frequent. As a Catholic and the grandson of a Mayan priest, Toribio’s vocation as an environmental steward is informed by a syncretic religious tradition.

“When John Paul II would visit a country, he would kiss the land,” Toribio recalled. “Mayan priests do the same.”

Another afternoon included a pilgrimage to the rectory of Blessed Stanley Rother, an American priest assigned to address the clergy shortage who, like Father Greg, made poverty relief and economic development central to his ministry. Beatified in 2017, Father Rother was outspoken in his condemnation of the civil war and the forces — Guatemalan and American — responsible for it. Marked for death by the pro-government paramilitary, he said, “A shepherd cannot run from his flock.” He was murdered in his rectory on July 28, 1981.

Joshua Santos ’20 (Pawtucket, R.I.) described his experience there, saying, “Father Rother’s love for his people in the community of Santiago was far more powerful than fear. As we visited and prayed inside his rectory, I felt a sense of wonder and awe. I am reminded of the responsibility we have to one another, and of the love we ought to show one another.”

In group reflections that grew longer yet felt shorter each night, students grappled with difficult questions. What does it mean to be an American visiting a country whose 36-year civil war began with a U.S.-backed, anti-democratic coup? How can solidarity be maintained over 2,200 miles’ distance? Does this enriching cultural encounter justify the resources spent facilitating it? Dillon described the dialogue.

“I think in the end most of them came to see that being committed to care for one another (solidarity) in a way that respects and supports the agency of those with whom we walk (subsidiarity) is crucial to all of our relationships, especially in the face of difference and inequity,” she said.

The questions weighed by students in classroom discussion and on the trip itself pointed to another question — what now? For several among this promising group, that question was already answered. Jack Murphy ’20 (Brunswick, Maine) spent this past summer serving in Nicaragua through a Fr. Philip A. Smith, O.P. Fellowship for Study and Service Abroad. Katherine Martinez ’20 (Stamford, Conn.) learned shortly after returning to Providence that she had been awarded a Newman Civic Fellowship for continuing commitment to service. Some students hope to return to the San Lucas Mission as long-term volunteers, and all considered what solidarity means at home and on campus. Despite his initial reservations, Jenness described how “removal from a familiar setting forced us to focus on what was around us. Back home, people struggle and suffer all the time; we often look right past it.”

As for Dillon, she will offer the course to a new group in the spring semester. “I believe that solidarity is an important virtue to resist the individualism and polarization of our times and believe that courses like this are very important in helping our students become the kind of people that we hope Providence College graduates will be,” she said.

At the reforestation project, Toribio offered students this wisdom: “Inside every fruit is a seed that we often throw away, losing our opportunity to plant it.” THL 375: Global Service in Solidarity and the trip at its center were fruits of concerted effort by students and their instructor, and they are planting seeds each day.

Michael Hagan ’15 is communications specialist in the Division of Marketing and Communications.