Writing on the wall: New course explores dialogue in a democracy

By Vicki-Ann Downing

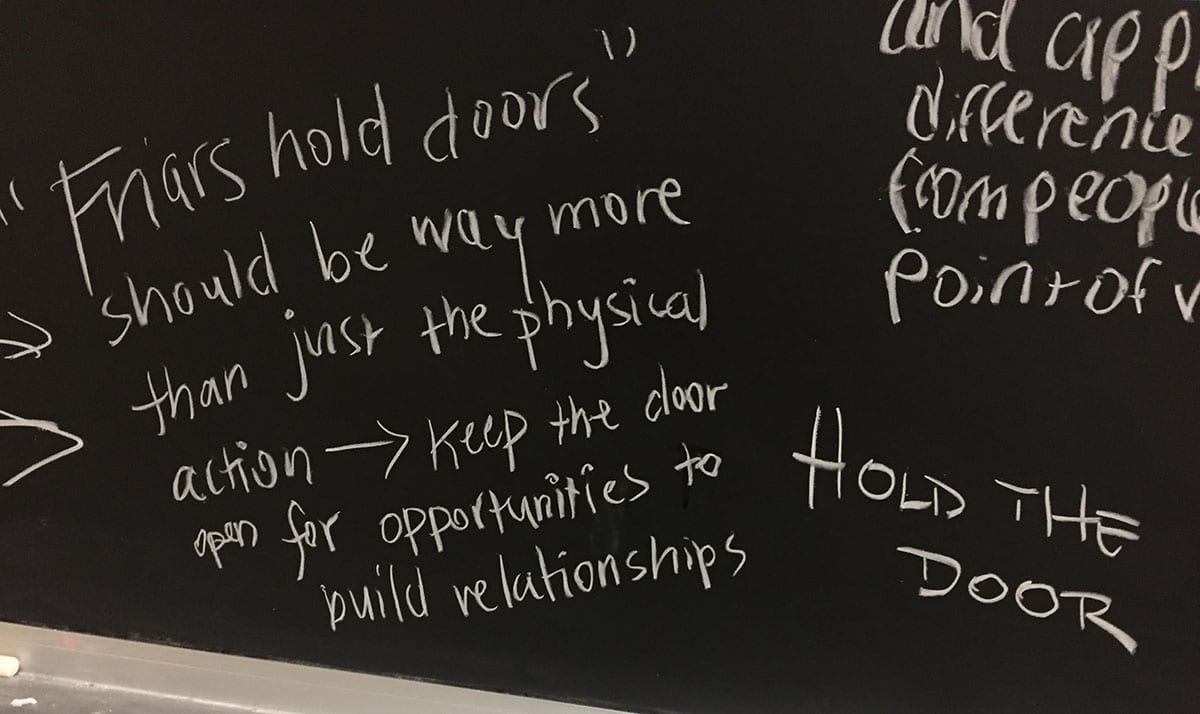

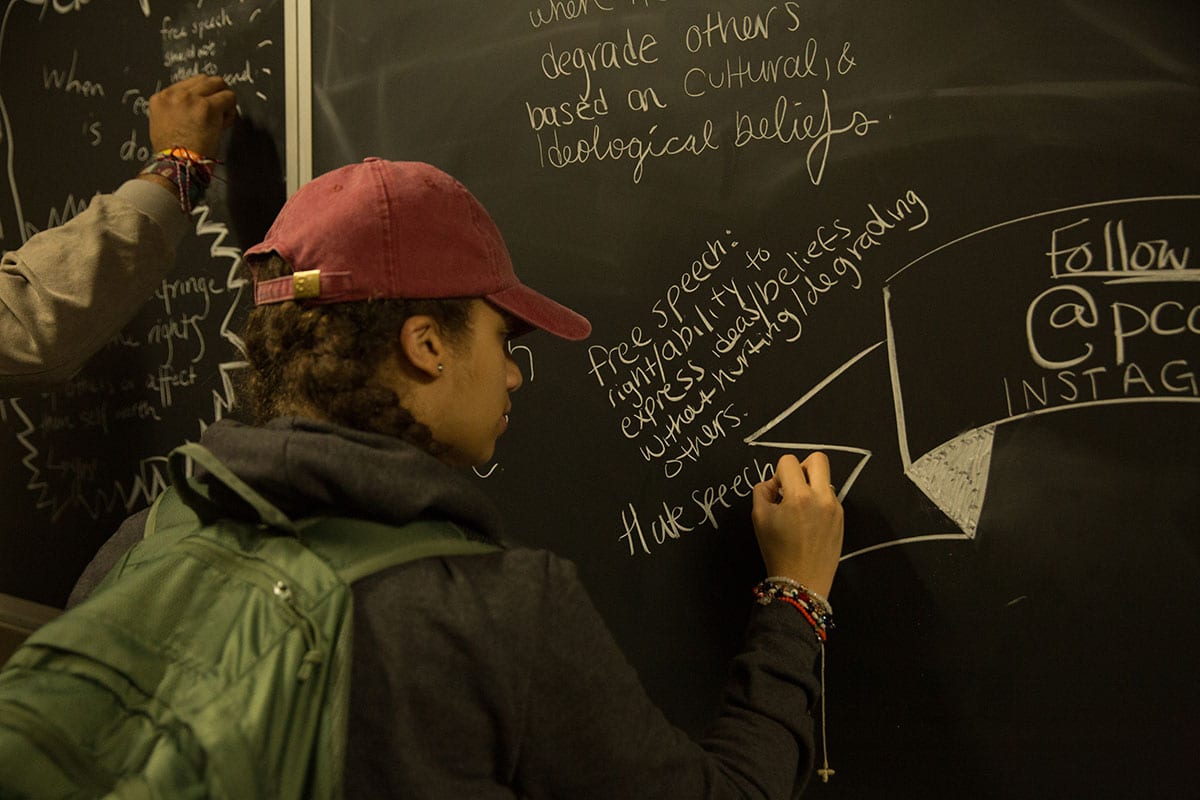

While politicians debated the value of a wall along America’s southern border, students in the Dialogue, Inclusion, and Democracy course at Providence College were creating a wall with a different purpose. Their Community DID Wall, located on the third floor of the Feinstein Academic Center, invites the campus community to a conversation on challenging topics:

What differentiates free speech and hate speech?

How is suffering part of the human condition?

How can we establish community at PC?

To join the conversation, “grab some chalk and leave your opinion.”

The Community DID Wall was the central project of a course taught in the fall 2018 semester by Nicholas V. Longo, Ph.D. ’96, professor of global studies and of public and community service studies, and Quincy A. Bevely, Ph.D., assistant dean of students and director of cultural education in the Office of Student Affairs. (In March 2023, Bevely was named PC’s inaugural assistant vice president for institutional diversity.) Two students, Marvin Taveras ’19 (Lynn, Mass.) and Caroline Garcia-Then ’19 (Lawrence, Mass), were facilitators.

Eighteen students took part, many of them leaders from student-oriented organizations, including the Board of Multicultural Student Affairs and Office of Residence life.

“We don’t know how to talk to people and have civil conversations, especially with people we disagree with,” Longo said. “This course was about how to facilitate those conversations. The wall is a place to have a dialogue about public issues with people of different backgrounds.”

Every two weeks, the class posed a new question on the wall and promoted it through an Instagram account (@didwallpc). Students, faculty, and staff passing through Feinstein wrote their responses, which the class monitored and discussed. In the classroom, the students studied active listening, methods of dialogue, story circles, and how to ask questions.

Six students are continuing the course as a research seminar in the spring 2019 semester. They are discussing how to make the wall sustainable. They have decided to add a second wall in the Center at Moore Hall and are considering a mobile wall that will travel around campus. They also are conducting research for an article that will be published in an academic journal.

The students also are in charge of adding new questions to the wall. Anyone is invited to submit a question to democracywall2018@gmail.com. The students invited College President Rev. Brian J. Shanley, O.P. ’80 and others in the campus community to submit questions, too.

The Diversity, Inclusion, and Democracy course was inspired by a book Longo is writing, Discussing Democracy, a primer for dialogue and deliberation on college campuses. The course is similar to a graduate class he teaches in PC’s Master of Education in Urban Teaching Program. Longo taught a pilot of the course in the spring 2016 semester when Taveras, a public and community service studies major, was one of his students.

“I’m very big on story-telling,” said Taveras, who has continued on as a student researcher. “I believe it’s powerful. It allows us to connect on an emotional level. This class taught us methods of dialogue that give us new ways to story-tell.”

The concept of the course, and the idea of a dialogue wall to connect the PC community, was developed in collaboration with a class on public art taught by Dr. Nuria Alonso García, professor of global studies and of secondary education and chair of global studies.

The DID class, which met in The Center at Moore Hall, was tasked with making the wall a reality. The students chose Feinstein as the location for the wall because of its proximity to classrooms and the department offices of global studies and of public and community service studies. They decided on its form — two chalkboards. They composed a mission statement and wrote guidelines for its use.

The DID Wall is meant “to create a safe space that supports the development of well-informed and engaged students through civil discourse,” according to information posted near it. The space was created “to activate new conversations and to share ideas, values, and visions for a better world. Disagreements may arise; however, personal attacks are not acceptable.”

The posted guidelines say that users should engage responsibly with the question and keep responses relevant; respect the humanity and dignity of others with regard to race, religion, class, sexual orientation, and gender identity; respect all responses, because the wall is “a free-speech zone;” and speak for themselves, not as representatives of others or groups. Advertisements, offensive language and profanity, and erasing others’ comments are prohibited.

Rodelyn Cherry ’19 (Brockton, Mass.), a health policy and management major and student researcher, said communication is key to resolving problems.

“A lot of progress happens when you talk it out,” Cherry said. “Dialogue is important when you’re facing difficult conversations. It took us three class sessions to name this wall. We heard from the entire class. Each question was a process.”

Bevely said student leaders from organizations across campus, as well as resident assistants who supervise students in the residence halls, were encouraged to register for the course. More than a third of the students were RAs, including Perla Castillo Calderon ’20 (Providence, R.I.), a public and community service studies major and student researcher.

“The class work helped me with some things I didn’t know how to deal with — difficult conversations with residents,” Calderon said. “It was one of the most practical courses I’ve taken so far and one of the most diverse. We had student leaders from almost every club.”

Bevely said the course instructors worked to create a sense of community among the students and to teach the importance of freedom of thought and expression. In their story circles, the rule was that no student could talk twice until everyone had talked once. Students were assured that their names would stay in the room, but their stories would carry on.

“We listened to everyone’s thoughts and figured out how to blend them,” Bevely said. “We taught the skill of active listening. Being able to hear a different perspective helps you understand your own perspective. Every voice is equally important. It’s not about agreeing. A beloved community is the beauty of different thoughts and perspectives reflected well.”