‘An Irish Interview’ with Dr. Paul O’Malley ’60

By Michael Hagan ’15, ’19G

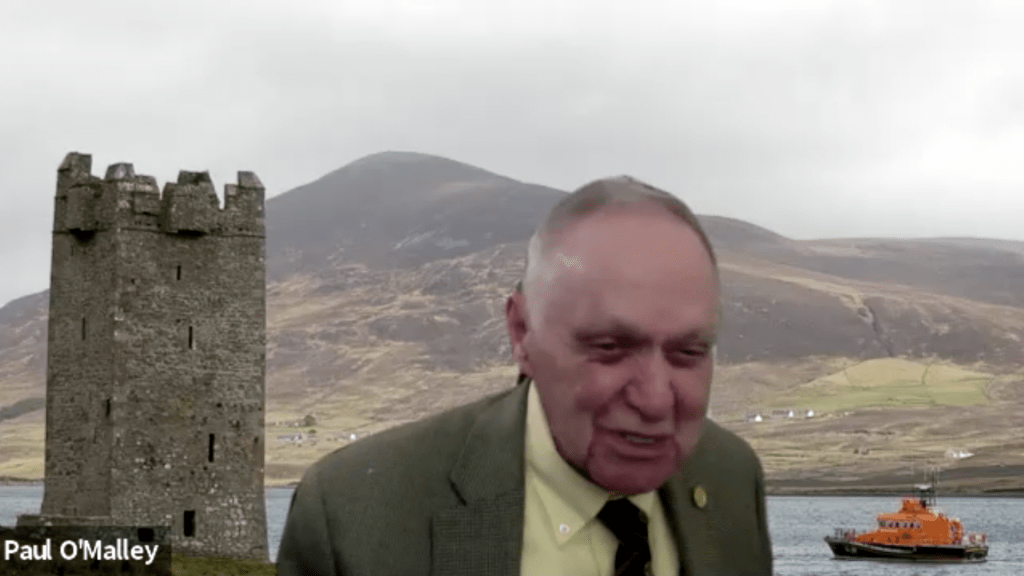

[Dr. Paul O’Malley ’60, assistant professor of history, appears on the screen for an interview via Zoom. Behind him is an image of a castle on the water with a hill in the background.]

Where do I have the pleasure of speaking to you today?

Welcome to County Mayo! This is one of Grace O’Malley’s castles on Clew Bay. It’s my usual backdrop when I’m on Zoom with my scholars.

When I was first exploring Providence as a student, I stumbled on a memorial downtown to victims of the Irish Famine. What does this memorial — almost easy to miss amid war memorials and historical sites dating back to Roger Williams’ day — tell us about the story of the Irish in Providence?

It speaks to the continuity of the Irish consciousness in Providence and Rhode Island. A sizable Irish population that had established itself in Providence and around Providence by, let’s say, the 1870s. Irish communities grew in Pawtucket, in Newport, in numerous mill villages — Woonsocket had a sizable Irish population even before it had a massive influx of French Canadians. And Irish immigration in the late 19th century coincided with large Italian and Portuguese migrations.

Now does the memorial connect to Irish immigrants who came to Providence in the course and immediate aftermath of the famine? Of course, very much so. But the influx of Irish into Rhode Island certainly predates the famine, though there was a real bump with the famine.

What prompted the migration of Irish before the famine?

There were varying degrees of economic opportunity in Ireland in the 19th century before the famine. Land hunger was a reality, especially among tenant farmers.

The extended aftermath of the 1800 Act of Union, which eliminated the independent Irish parliament, involved a loss of industrial activity in the Irish countryside associated with things like linen manufacture accelerated by industrialization as this labor shifted to urban factories. As opportunity diminished for cottage industry producers who had previously flourished, many emigrated. So, many of the first Irish to arrive in Rhode Island brought a particular set of skills in textiles. I’m thinking of those who came to establish what is now the oldest church building in the Diocese of Providence — St. Mary’s in Crompton, a section of West Warwick. Those people predate the famine and were ready candidates to work the burgeoning textile mills.

The Irish who arrived pre-famine would also provide much of the muscle for the digging of the Blackstone Canal and the building of railroads. Many women found employment in the big houses on the East Side as maids and domestic workers.

What were their experiences like upon arrival?

An event that helped to define the outlook of the Irish in Rhode Island took place before the famine. On New Year’s Eve in 1843, Amasa Sprague of the Sprague textile family was brutally slain as he made his way toward some of his lands on the fringe of St. Ann’s Cemetery in Cranston near where the 1025 Club used to be. Indicted for the murder were several brothers by the name of Gordon. Nicholas Gordon was a fairly comfortable Irish immigrant who ran a general store. He was targeted because the Spragues had effectively curtailed his business. In a travesty of justice, one of the brothers, John Gordon, was convicted. He was executed on Valentine’s Day, 1845 — before the famine.

That was a traumatic event for the Irish. It was actually a factor in Rhode Island’s subsequent abolition of capital punishment. The very last execution in Rhode Island was that of an Irishman — John Gordon — in 1845.

What neighborhoods in Providence had large Irish Immigrant communities?

At the peak of Providence’s numerical Irishness in the late 19th century, they came in significant numbers to Fox Point. They also came to what would become downtown Providence around Dorrance Street and the Westminster area. It wasn’t upscale then; it was tenements. There was a huge Irish population in South Providence and in Olneyville. And, interestingly enough, a great influx especially of Tyrone people who settled in Federal Hill. The first Catholic church on Federal Hill was St. John’s, the Irish church. In what became Smith Hill, St. Patrick’s Church was erected for great numbers who came in to work the mills.

Then there’s the Irish North End, which fostered the creation of the Church of the Immaculate Conception, where I was baptized. Many of these congregants worked in the Corliss Engine Works, whose Corliss engine was heralded at the Centennial Exhibition in 1876 in Philadelphia as the masterpiece of American industrialization. It’s the neighborhood I was brought into as a baby. The name isn’t used much anymore, but it was the Corliss Heights area of the North End. The heart of Corliss Heights stretched from the beginning of Admiral to Berkshire Street.

[I take a breath to begin to ask my next question. As anyone who knows O’Malley knows he is liable to do, he preempts me with another fascinating bit of history.]

Now, it’s worth noting that many of Providence’s Irish neighborhoods were not originally in Providence. For example, when my great-grandfather Michael O’Connor, a Civil War veteran, died in 1873, his place of death was listed as North Providence. Why did this area become part of Providence? Because of the Irish. There were so many Irish coming into North Providence that it could enable the Democrats to send representation to the General Assembly from the area. Parts of Johnston were also brought in for the same reason.

What role did the Church play in these immigrant communities?

It was absolutely central. The Irish were known for walking for miles in from mill villages where there weren’t churches to St. Peter and Paul’s, now the cathedral. The Church obviously provided liturgy and sacraments. Schools would come in time. The Catholic parochial junior high school that I graduated from was the school of the cathedral parish. Interestingly enough, it was named after the first bishop who lived in Providence, the convert William Tyler. He was officially the bishop of Hartford but lived in Providence because of the exploding Irish population. Several of his successors also lived in Providence. The very first bishop of Providence was Thomas Hendricken — more of a German name than an Irish name, but a proud Irishman out of Kilkenny.

To anyone who is interested in the history of the Irish and the Church in Providence, I’d recommend Father Robert Hayman’s masterful study: Catholicism in Rhode Island and the Diocese of Providence, 1780-1886; its second volume, 1886-1921; and his recently published third volume, 1921-1948.

[Editor’s note: Rev. Robert Hayman formerly taught in the Department of History]

Providence College was founded to serve the educational needs of working-class and immigrant families in the Providence area. What obstacles did the Irish and other ethnic communities face in pursuing education and opportunity?

Opportunities were limited. For women, there was the opportunity for a “normal school” education to prepare them to teach. There were significant numbers of Irish women who taught in Rhode Island schools. The University of Rhode Island was getting its legs, and there wasn’t a particularly warm welcome for children of immigrants. As Brown University was transitioning from more of a religious, Baptist institution, there wasn’t a warm welcome for Catholic immigrants. Comfortably well-off Catholic youngsters would go up to the Cross — Holy Cross — in Worcester. But for the rest, opportunities were limited.

What Providence College did was offer to the sons of immigrants — plenty of Irish, but also Italians, French Canadians, Poles, Portuguese, Cape Verdeans, Lithuanians, and Lebanese — a relatively inexpensive higher education with a Catholic doctrinal underpinning and an open welcome to non-Catholic students.

Your interest in Irish history is academic but also deeply personal. Where does your family fit into the story of the Irish in Providence?

I have four Irish immigrant great-grandparents who came to Providence. The first would have been Bridget McNally, who settled with her parents in what was then North Providence right in the vicinity of the Brooklyn Coffee House and St. Patrick’s Cemetery. Next to arrive was the man who would marry Bridget, Michael O’Connor. He hits the records of history, as far as I’ve gathered, in August of 1862 when he joins the 21st Massachusetts Infantry Volunteers Regiment. He’s badly wounded at Fredericksburg. His unit practically reaches a wall in Fredericksburg where behind the wall are Irish Confederates from the Jasper Greens cheering their kinfolk’s bravery while shooting at them.

By the time Bridget McNally marries Michael O’Connor, my great-grandfather, George O’Malley, settled across the street from where the Marriott is now. The records aren’t great, but he probably comes from a town in County Mayo in the midst of which sits the ruins of a Dominican priory, so I suppose it was in my destiny to teach at Providence College. His son marries the last of my Irish immigrant forbears, Annie Surlis (Searles) from County Roscommon. So the four of them are here by 1869.

[O’Malley walks verbally down each branch of his family tree, recalling impressive amounts of detail about each relation, the street and block where they lived, and their trades — too much to include in full here.]

I grew up with a strong Irish consciousness, but I’m not exclusively Irish. My dad, who had an eighth-grade education, opted for a retail trade and became a shoe salesman and manager in downtown Providence, where he fell madly in love with my beautiful mother, Helen Baker, who was one of 11 children. Her family history runs from Russian Poland, through England, to Toronto, to Buffalo, to Fall River, and finally to Chalkstone Avenue in Providence.

I was the first of my parents’ eight children, and when they had no place to stay when I was born, they moved in with my widowed grandmother, Margaret Loretta O’Connor O’Malley, at the corner of Donelson and Admiral streets. On my father’s knee I came to appreciate deeply my Irish heritage and Catholic faith. But I embrace the Jewish heritage of my convert mom’s family equally.

Tell me about where you lived growing up.

By the time I married my wife of 56 years, Carolyn Evelyn Donahue, I had lived in about 12 or 13 houses in my native Providence; in Worcester; in Auburn, New York, on the Canadian border; and in Pawtucket. I lived in very different parts of Providence — directly behind the cathedral, the Chad Brown-Admiral Terrace housing project, in Holy Name Parish on Cypress Street, and on Summit Avenue. These multiethnic areas had significant populations of Irish background.

Any favorite memories?

When we moved to Foster Street, across from St. Xavier’s, my heart was kind of broken. I was leaving my buddies at St. Edward’s in Fairlawn and just getting my wings on my bicycle. When we were living in South Providence, I convinced one of my buddies to go looking with me for Queen Esther’s Cavern in North Kingstown. So we took off to North Kingstown; I had a grand total of 10 cents in my pocket. We made it there and back, and when we returned, who was outside the O’Malley tenement — the Providence Police Department. I gave my parents quite a scare. Later, I would go bicycling down the Francis Street hill and come close to being wiped out on my way to visit friends in South Providence, but you fear not at that age. It’s a wonder I’m here talking to you.

How did you spend your time growing up?

I worked at an early age. I had my paper route on Pine Street. When I graduated from the Tyler School in ninth grade, I became the janitor of a five-story 19th century Mercy Hall at St. Xavier’s Academy. I cleaned it every evening all through high school and my first two years at PC. I was there long enough to become an “honorary graduate” of that all-girls school. That school was founded by the great Sister of Mercy, Frances Xavier Warde. She founded St. Xavier’s Academy, which was set upon by nativists in the mid-19th century.

On the topic of growing up with a deep Irish consciousness you mentioned, how did Irish culture permeate your childhood?

The story of the execution of John Gordon I mentioned was instilled in me. But otherwise, my father loved music. He would make a point to talk about great Irish music. My family was very musical. My uncle had a great singing voice, and there was a routine where you’d pressure him to sing, and he’d play humble but eventually perform. It’s not an Irish song, but he’d sing “On the Street Where You Live” from the wonderful musical My Fair Lady. I was schooled in the great Irish music tradition. My father’s favorite Irish song was “A Little Bit of Heaven.”

Was there much said about Ireland? Not that much was said about the experiences of my forbears there. But there was pride in being Irish. I’ll give you an example. My father’s younger brother, Robert Emmet O’Malley, was named after the great United Irish protestant poet who was executed in 1803. His speech from the dock on the occasion of his gruesome sentence which involved hanging and beheading was standard fare not only for young Irish people, but for Abraham Lincoln, who learned the speech. My youngest brother and first cousin, a Providence College graduate, share the same name.

When did your natural interest in Irish history and culture grow into an academic interest and eventual vocation?

When I was in the ninth grade, the Ancient Order of Hibernians sponsored an essay contest. I didn’t win, but I researched Daniel O’Connell. I studied biology with the intention of going into medicine as an undergraduate at PC, but I left medical school and transitioned into history. There really wasn’t an Irish history course at URI where I took my degree in modern European history with a focus on 19th century France. When I did my doctoral studies at Boston University, my mentor was a scholar of Scottish history. I asked if I could do a topic in Irish history for my dissertation, and he agreed. So I spent a number of years researching the development of Irish neutrality in World War II, centering on the Spanish-Irishman Eamon de Valera, who led the Irish Free State/Eire in the 1932-1939 run-up to the war.

I will always be unbelievably grateful to Providence College for giving me the opportunities it did and for the Dominican friars. I’m also forever grateful to the Sisters of Mercy, the Brothers of the Christian Schools, and to the lay faculty who have taught me. The education I received at their hands is value-loaded in the best sense. With it, I was ready for anything in life.

[We get to talking about life under the circumstances of the pandemic. He talks about enjoying and even performing Irish music with colleagues and friends. I’ve come to expect unexpected facts and stories from O’Malley, but I’ve never heard him sing.]

When will we get a chance to hear you sing?

Soon, I hope. God, yes, there was a life before all this. I can’t wait to get back to it. Dr. Sickinger (professor of history) and I put an event about Ireland in song and story on in 2018. He has a wonderful singing voice and sang Irish folk songs. I joined in on a number of the choruses and stanzas myself. Right after it, the student Irish Dance Club put on a presentation, and my Irish club’s group followed. They got quite a bit of applause. I can’t wait to witness things like that again.

[As I check the time, I realize hours have passed. That’s how it goes with O’Malley; the present moment stands still as the still past becomes animated. I note the time, and O’Malley chuckles. “It was an Irish interview,” he says with a smile. Indeed, it was.]