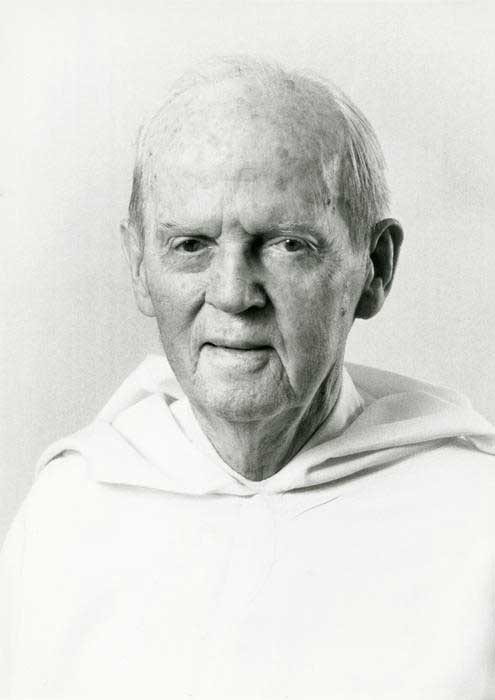

Rev. Edward Doyle, O.P. ’34, the ‘Dominican liberator,’ wanted all to know ‘the Holocaust happened’

By Ealish Brawley ’14

Twenty five years after his death on April 12, 1997, Rev. Edward Paul Doyle, O.P. ’34, fondly known as the Dominican Liberator, continues to inspire those who learn about him.

Father Doyle served a professor of theology at multiple universities, including Providence College, a research fellow at Yale Divinity School, a college chaplain, a hospital chaplain, and a priest in parochial ministry, but he is most remembered for his role as an army chaplain in World War II. The infantry division to which he was assigned liberated the Nazi concentration camp at Nordhausen, Germany. His message about trust in God’s goodness and the importance of Holocaust remembrance endures in the special collection of documents he donated to PC.

Born in 1907, Father Doyle grew up in Fall River, Mass., with his parents and eight siblings. He joined the Order of Preachers in 1932, earned a bachelor’s degree from PC in 1934, and was ordained to the priesthood on May 17, 1939. He received a master’s degree from The Catholic University of America in 1941 and then taught theology at PC until 1954, with the exception of a three-year interruption for military service. In the wake of Pearl Harbor, Father Doyle applied for duty overseas, and in 1943 he was called to be a major in the chaplaincy corps with the 104th Infantry Division, also called the Timberwolves.

At a special event to honor the life of Father Doyle held during the college’s centennial celebrations in 2017, College President Rev. Brian J. Shanley, O.P. ’80 recalled his impression of the Dominican Liberator, who was an elderly priest when Father Shanley joined the order.

“We never called him Father Doyle. We just called him Major Doyle,” Father Shanley said. “He was always Major Doyle. That military period of his life was so formative for him.”

Father Doyle was a chaplain from 1943 to 1945. In a letter dated Nov. 6, 1945, to College President Rev. Frederick C. Foley, O.P. ’29, Major General Terry Allen described how Father Doyle ministered to all men in his division regardless of their religious beliefs, often disregarding his own safety.

“I know that any man associated with Father Doyle will miss him, because of his fine spiritual and moral help which he so unhesitantly gave for his men. There were times when Father Doyle celebrated Mass under shelling, and there were times when he, without being asked, went willing and well forward into the danger zones of the division to render his consoling thoughts to the men just going into or coming from combat,” Allen wrote.

Enclosed with the letter was a copy of Father Doyle’s Bronze Star Medal Citation, which Father Doyle’s regimental commander requested he receive for service during the Ruhr River Crossing.

Although Father Doyle undoubtedly saw horrors on the battlefield in the midst of combat and ministering to the wounded, nothing compared to what he witnessed during the liberation of Nordhausen.

On April 11, 1945, Father Doyle and the Timberwolves arrived in Nordhausen, the site of a concentration camp called Mittelbau-Dora, which originally was a sub-section of Buchenwald. Prisoners were sent from Buchenwald to Nordhausen to assemble V-1 and V-2 missiles in an industrial complex tunneled into the surrounding hills. They often spent weeks within the tunnels without seeing daylight or breathing fresh air. Shortly before liberation, the Nazi SS evacuated able-bodied prisoners to Bergen-Belson, another concentration camp in northern Germany.

In 1981, Father Doyle described the scene at Nordhausen during his address, “I Was There,” at the International Liberators Conference in Washington, D.C.

“It was said we discovered 6,000 political prisoners, but alas 5,000 were corpses,” Father Doyle said. “A sight beyond description; mutilated, beaten, starved skeletons; 1,000 were ‘living’ in various stages of decay, merely breathing among the already dead.”

During the effort to tend to the sick and bury the dead, Father Doyle captured haunting photographs with a Polaroid camera issued by the Army for the purpose of collecting evidence of atrocities.

“Facts and details overcome one as memory conjures up the scene over and over again. And, yes, my photographs bespeak a thousand words for the wholesale slaughter and slow death, which was not restricted to men but to women and children also,” Father Doyle said.

Father Doyle’s photographs now are the heart of the Father Edward Doyle, O.P. Collection in the Providence College Archives and Special Collections. Along with the photos are personal letters, newspaper clippings, recorded interviews, and obituaries, all of which have been digitized and are available on the college’s Digital Phillips Memorial Library.

Father Doyle entrusted the materials to his colleague and friend, Jane Lunin Perel, MFA ’15Hon., professor emerita of English and of women’s and gender studies, shortly before his death in 1997. He left PC in 1954 for other academic and ministry roles but returned in 1976 to live at Saint Thomas Aquinas Priory on campus and serve in a local parish and as a hospital chaplain.

In a documentary produced for the centennial celebrations in 2017, Perel recalled Father Doyle’s words to her that day: “I want you to take these. And I want you to make a public space where these pictures and other parts of my archives will always be visible, so that everyone who comes into Providence College will know the Holocaust happened.”

Jacqueline Michels ’19, ’21G, who wrote her senior thesis on Father Doyle, first heard of the Father Doyle Collection during a seminar on Germany with Raymond Sickinger, Ph.D. ’71, professor of history.

“When it came time to think about my thesis in 2018, I remembered what Dr. Sickinger said about the archives, and that no history student had yet written a thesis on them,’’ Michels said.

Studying the collection and writing “The Dominican Liberator: Father Edward Doyle, O.P.’s Response to the Holocaust,” was personal for Michels. In addition to the strong connection to PC, a place she calls “one of my homes,” Michels chose to study Father Doyle’s archives because her father and his family are Jewish.

In her thesis, Michels argued that the Dominican charism allowed Father Doyle to process his experiences in World War II, and especially the liberation of Nordhausen, without losing his faith.

“He trusted that God was watching over His children during the Final Solution. He asserted that all of the Jews who were killed were sent back to God. He trusted in the goodness of the Lord and his forgiving nature,” Michels wrote.

The particular mission of the Order of Preachers is to contemplate and share the fruits of that contemplation. They preach for the salvation of souls, and Father Doyle’s actions and words were a comfort to others, letting them know they could trust in God’s love and care despite the suffering around them.

During an interview with two other chaplains at the International Liberators Conference, Father Doyle explained how his faith in God’s goodness was able to survive the Holocaust.

“The Holocaust was the tragic failure of man. So it isn’t God who failed, man failed … We need God more than ever. This, to my mind, didn’t jeopardize my faith. It indicated to me that we have work to do. Man has failed, not God,” he said.

In a June 12, 1982, article in the Providence Journal-Bulletin, “Priest turns anger of Holocaust into life of joy,” Richard C. Dujardin drew a conclusion similar to that of Michels. Describing the priest’s final assignment as chaplain at Summit Medical Center in Providence, Dujardin wrote that Father Doyle believed that genocide was the result of people’s failure to love. It was every person’s responsibility to become instruments of God’s love, especially for those who suffer. The way Father Doyle spent his last assignment, ministering joyfully and bringing God’s love to Summit Medical Center’s residents, affirms Michels’s and Dujardin’s analysis of this man of faith.

After her graduation in 2019, Michels joined the Providence Alliance for Catholic Teachers, PACT, and earned a master’s degree in education from PC while teaching history at two local Catholic schools. She is now a history teacher at Lincoln High School in Lincoln, R.I., teaching 10th and 11th grade world history and US history.

The first student to explore the Father Edward Doyle, O.P. Collection in depth now teaches lessons on the Holocaust to her young students.

“We need to remember why we teach the Holocaust: Not just that it happened in history, but we need to remember it respectfully and work so that an event like this will never happen again,” Michels said.