Patrick Kennedy ’91 is a leading advocate for mental health and addiction care

By Vicki-Ann Downing ’21G

Patrick J. Kennedy ’91 didn’t have a typical student experience at Providence College.

The son of Massachusetts Senator Edward M. Kennedy and the nephew of President John F. Kennedy, he struggled privately with addiction and bipolar disorder from his early teens. When he withdrew from Georgetown University after only a few weeks, his father’s friend, Connecticut Senator Christopher J. Dodd ’66, ’83Hon., suggested he try Providence, which might be “a fresh start in a smaller fishbowl.”

Kennedy majored in social science. Terrified that his mental health struggles would become public and embarrass his family, he lived alone in an apartment off campus. Getting out of bed for class was a challenge. Picking up his mail in Slavin Center sometimes caused total panic. He regularly saw a psychiatrist, Peter Kramer, M.D., who taught at Brown University and later became famous for his book, Listening to Prozac.

Some experiences were familiar, though, Kennedy said in a Zoom interview in January 2024.

“Western Civ,” Kennedy said. “Being in the library listening to all the tapes all the time” because he couldn’t take notes fast enough in lectures.

History professor Raymond Sickinger, Ph.D. ’71 “was a terrific mentor for me, providing guidance through all my years at PC,” Kennedy said. He mentioned other Friars with whom he remains in touch: Jim Vallee ’88, Student Congress president and now a partner at Nixon Peabody LLP; Bill Daley ’94, managing director at Goldman Sachs; Chris Vitale ’95, principal at Capital City Group. At airports, “you always run into a few Friars,” Kennedy said.

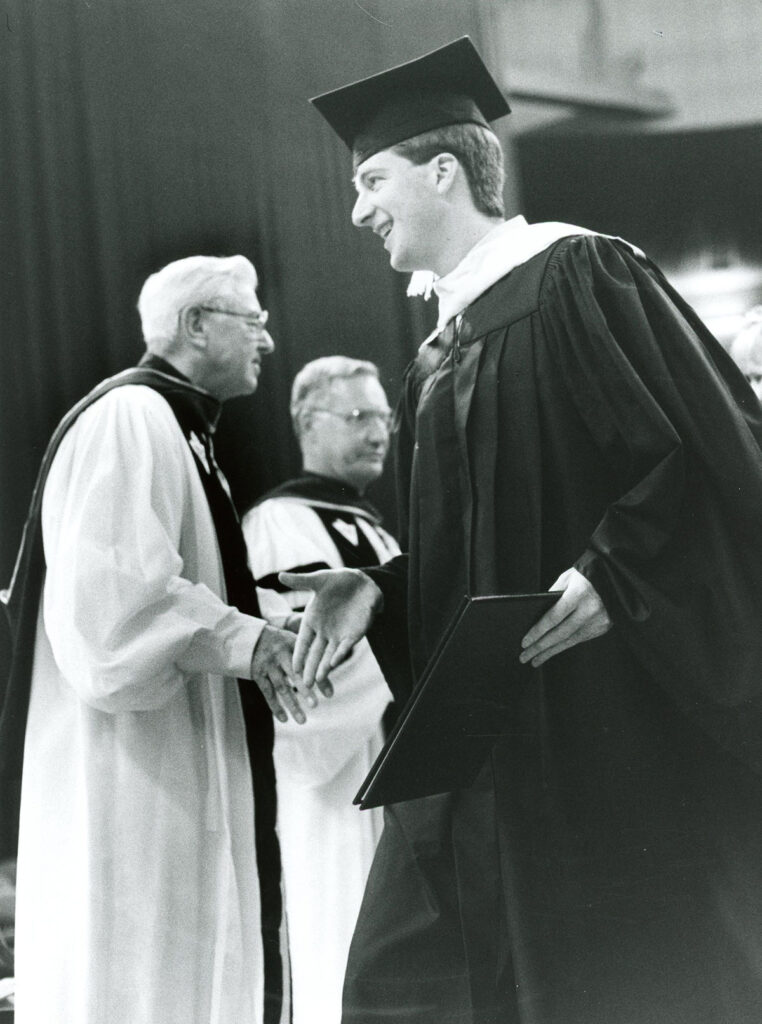

Despite his health challenges in college, Kennedy launched his political career while a student. He began with an internship at the Rhode Island State House, then ran for state representative at the start of his junior year for the district that includes PC. He served two terms before running for U.S. Congress in 1994. He represented Rhode Island’s first congressional district in the House of Representatives for 16 years. His signature achievement came in 2008 — passage of the Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act, which requires health insurance companies to provide coverage for mental illness and addiction treatment as they would other illnesses.

The Senate version of the parity bill, co-sponsored by Kennedy’s father and backed by health insurance and pharmaceutical companies, did not mandate coverage for substance use disorders. The version Patrick co-sponsored in the House did. He and colleagues campaigned hard for their version and held field hearings around the country. In the end, addiction treatment was included in the final bill signed into law by President George W. Bush. It ended the discrimination that is at the heart of the stigma of brain disorders, Kennedy said.

Over the course of Kennedy’s 16 years in Washington, he became more open about his struggles. He admitted in 2000 that he had been treated for depression and in 2006 that he was addicted to painkillers. Even so, as he acknowledges in his book, A Common Struggle: A Journey Through the Past and Future of Mental Health Illness and Addiction, he didn’t fully tackle his mental health and addiction issues until after leaving Congress in 2011, when he began the longest period of sobriety he had experienced since age 13.

“Our secrets are our most formidable adversaries,” Kennedy wrote. “The older I get, the more I see secrecy as ‘the enemy within,’ which blocks recovery not only for individuals but for society itself.”

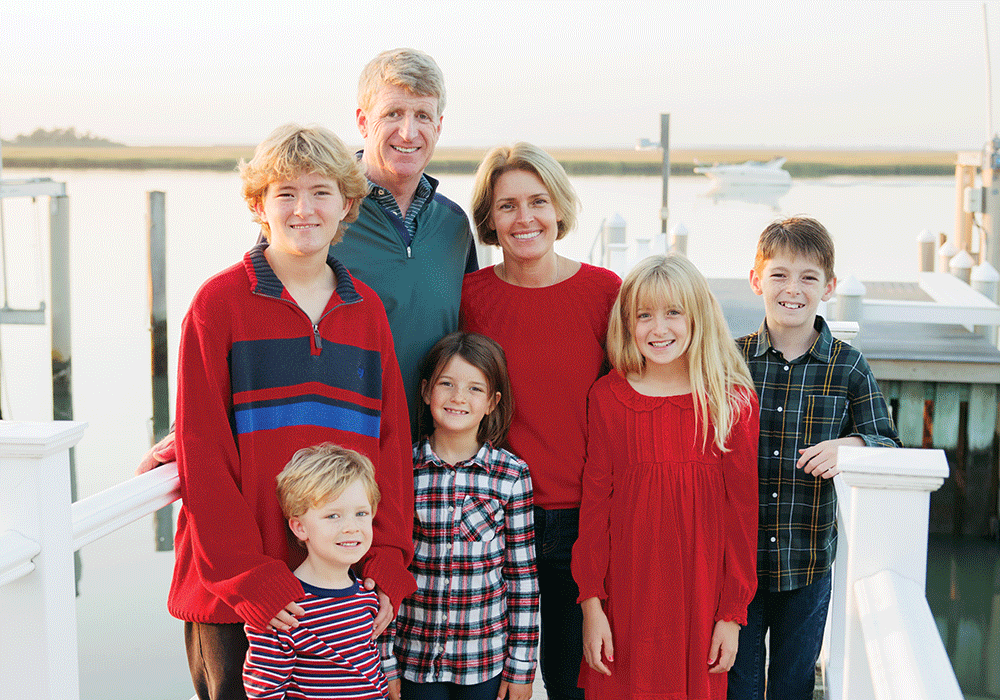

Since leaving Congress, Kennedy has resided in Brigantine, New Jersey, with his wife, Amy, and their five children. He is one of the nation’s leading voices on mental illness and addiction. He established the Kennedy Forum, a mental health leadership initiative created to enforce the parity act, strive for improved care, and build a nationwide community of mental health experts and advocates. He is the co-founder of One Mind, a nonprofit that focuses on funding for international brain science research. He continues to work with Smart Approaches to Marijuana, an organization concerned that commercialization could create the next Big Tobacco and that the full effect of THC on the brain remains unknown. In his new book, Profiles in Mental Health Courage, published in time for Mental Health Awareness Month in May 2024, he chronicles the stories of a dozen people who share their struggles with mental health and addiction, many for the first time.

In January, Kennedy announced that he would join Healthsperien LLC, a healthcare consultancy based in Washington, D.C., as a partner and lobbyist on issues related to mental health and addiction.

Most important, Kennedy has continued to advocate for honesty to reduce stigma. He remembers how relieved he was as a PC sophomore to be diagnosed with a benign tumor of the spinal cord because it was a health issue he could be open about and that drew sympathy from others. He remembers the overwhelming support his family received when his older brother was diagnosed with bone cancer and contrasts it with the reaction when his mother admitted her battle with alcoholism.

What message would he offer PC students? Don’t be ashamed to seek help, because help will make you stronger. Just look at the Green Berets.

Kennedy recalls a visit to the John F. Kennedy Special Warfare Center at Fort Bragg, North Carolina, where the Army trains its Special Forces. General Hugh Shelton told Kennedy that “Special Ops” had the best mental healthcare of any branch of the service. When Kennedy asked why, Bragg told him, “We don’t look at mental healthcare as a safety net. We look at it as a force multiplier.”

“Stigma is based on the sense that you are weak if you need mental healthcare,” Kennedy said. “But what do the Green Berets rely on for their lives in the field of battle? They need to know they won’t have intrusive thoughts or be ruminating about what happened last week. They can’t be worried that their inability to channel their thoughts will impact their duty to be aware and manage their surroundings. They manage counterproductive thought patterns. They aren’t the only ones. Corporations now have coaches to support their C-suite employees and make their executive workforce more productive.

“If you’re able to self-modulate, manage stress, and have coping skills, it makes a better result,” Kennedy said. “Students won’t just ace Western Civ, they’ll learn how to understand their own mental health, and at the end of the day, this is premium value.”