February 18, 2025

Reflections from Providence College’s first study abroad student

Editor’s note: More than 50 years ago, in the fall of 1962, Raymond G. LePage, Ph.D. ’64 became the first Providence College student to study abroad. Dr. LePage was associate professor emeritus of French at George Mason University when he wrote this reflection in 2012. He died on February 6, 2025.

By Raymond LePage, Ph.D. ’64

In the spring of 1962, I decided that I wanted to spend my junior year studying at a European university.

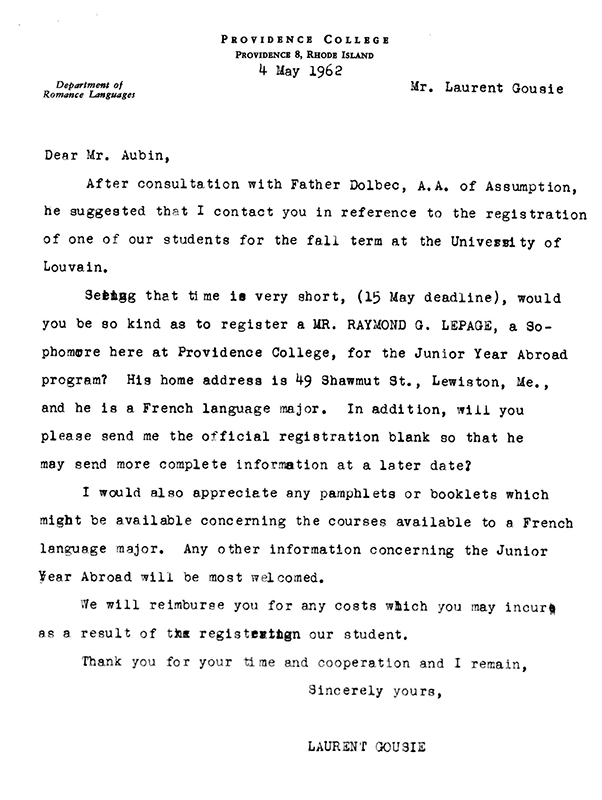

I was a modern languages major with an interest in literature, philosophy, and history. I spoke to my young professor of German at Providence College, Laurent Gousie, Ph.D., who was very encouraging. He told me that PC had no study abroad program, but he would be glad to help me find an institution. I did my own research, and decided that I wanted to attend Louvain University in Belgium.

“Why Louvain?” he asked me.

I told him that it was a great Catholic university going back to the Middle Ages, with a proud history of scholarship and a prestigious international reputation.

“You’ll be on your own,” he told me — PC had no affiliation with Louvain.

I did not fear the challenge, because Louvain was a French-taught university and I spoke French at home before I spoke English. I also liked its location in the heart of western Europe with easy access to all major countries. I was a bit arrogant and confident back then, welcoming all cultural obstacles and difficulties.

“I can handle any problems,” I told myself.

The experience taught me that I was too confident.

The procedure worked out by the PC administration was: For purposes of credit transfer, I would pay PC the usual tuition for both semesters of full-time course work. All other expenses incurred would be on me.

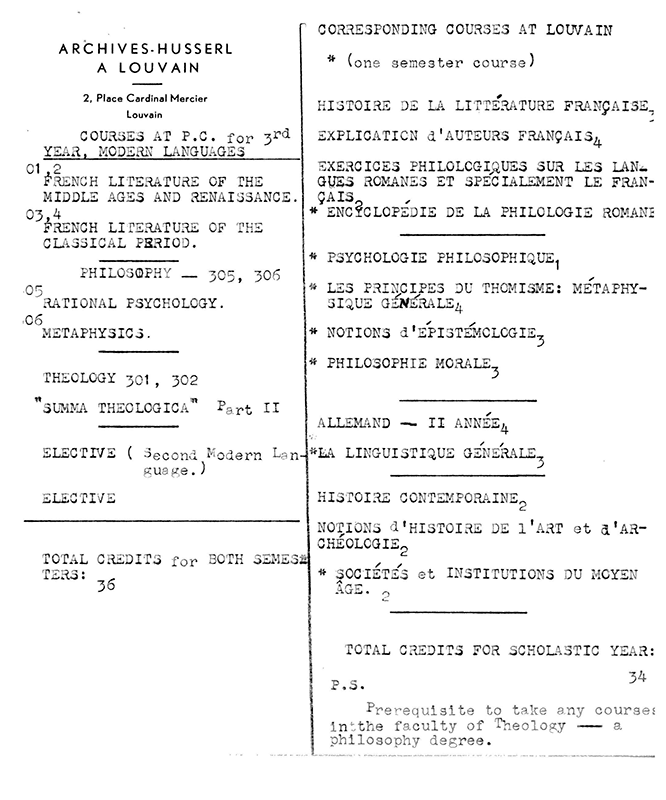

Professor Gousie helped me draw up a list of appropriate courses for each semester. With a letter of introduction from our dean, Rev. Joseph L. Lennon, O.P. ’40, ’61Hon., I eagerly awaited the month of August, when I would board a Greek passenger liner in Montreal for Amsterdam and the new cultural life beckoning me beyond the sea.

Arriving on the eve of change

After disembarking in Amsterdam, I spent several days sightseeing, visiting museums and other points of interest. I was anxious to get to Louvain, so I took a train to Brussels, then Louvain — or “Leuven” as it was known by the local Flemish-speaking population.

It did not take me long to realize that Belgium was divided into three parts: The Flemish-speaking northern part, the French-speaking southern part (Wallonia), and the middle or neutral Brussels area with a mixture of both ethnic groups. Louvain was in the Flemish-speaking section of the country, but still remained a francophone university because of its long academic reputation.

Nonetheless, my year at Louvain saw the acceleration of a bitter national ethnic divide which would culminate in the separation of this venerable university into two different parts of the country — only Flemish-taught in old “Leuven,” and a new French-taught university campus to the south, known as “Louvain Nouveau.”

I did not know it then, but I was among the last generation to attend this great, integrated university of international importance, which would never be one again. I arrived at the city’s main railway station at twilight without realizing that I would be a witness to the sad twilight of historical Louvain’s final glory years.

It would not survive intact beyond the decade.

Finding a place to live

I checked into a nearby hotel. I wanted to find lodgings as soon as possible. The next morning I walked down Louvain’s main street and was awestruck by the architecture, the restaurants and boutiques, in front of which cleaning maids were washing the sidewalks.

The streets and sidewalks were all cobble-stoned. The beautiful university and town buildings, some dating to the 14th Century, were quite remarkable. All this was definitely “Old World.”

There was a sign posted on many buildings stating that all newly-arrived international students had to register at the International House as soon as possible.

Walking along the main commercial street, I spotted a notice on a fashionable men’s clothing store that a room was available for rent and to inquire within. It was a four-story building, with the clothing shop on the main floor, the owner and his family occupying the second floor, and students occupying the third and fourth floors. The room available was on the top. It was the only room up there, fully furnished, with a sink and a balcony with a gorgeous view of the old, medieval town.

The price of the room included daily cleaning maid service except on Sundays. I couldn’t believe how inexpensive it was. This was the age of king dollar, and I accepted it without haggling over the price.

I was an only child and by nature a loner, and since my French was quite good, I could come and go as I pleased. At the time I thought I had made the right decision. Nowadays, most students studying abroad like to stay with a local family, which has its advantages. Living haphazardly with just any family in Louvain would’ve posed problems for me, since the local population was Flemish and did not like to speak French out of ethnic pride. They would if they had to, but preferred speaking English over French if they knew you were American.

Registering for classes

After moving into my new quarters, I decided to go to the International House and register as requested. It was a big building filled with French-speaking foreign students from everywhere as well as university administrative workers. There were also visiting professors and what looked to me like medical personnel.

On the entry level was a large information desk where all students were asked to produce their passport and immunization card prior to proceeding. Since I had mine, my passport information was officially recorded, and I was told to go to the end of this large room with my immunization card for a physical exam. After passing the exam and paying a health insurance fee of $10 for the new academic year, I was sent to another side of the building with the necessary documents to properly register as a Louvain student.

Each student awaited his turn for the next available registrar in order to be placed in the correct degree program. When it was my turn, I stood before a small owlish man with bulging eyes and a walrus mustache on an acerbic face. He was baldheaded and wore spectacles which dangled at the end of his nose. He seemed very elderly to me and quite officious-looking with a buttoned-down suit, stiff collar and plain cravat.

While he was perusing my documents I introduced myself.

“Bonjour, Monsieur,” (our conversation was entirely in French), “I’m an American student from Providence College.”

He looked up, practically shouting “Providence what?”

‘That is not how we do things in Louvain’

I proudly showed him Dean Lennon’s introductory letter, which he barely glanced at and returned to me with a flick of the wrist. However, I had come prepared and smugly pulled out the list of courses that I wished to take while at Louvain. He then became very flustered and exclaimed “Voyons! Voyons!” (“Ah, C’mon! C’mon!”)

He must’ve thought that I was playing a game or teasing him, for he looked at me as if I were the most deranged person in the building. He undoubtedly ascribed my behavior to American naiveté, for he calmed down and simply said: “That is not how we do things at Louvain, Monsieur.”

“I see that you wish to study languages and literature, philosophy and history, therefore you will be duly enrolled in the Faculte´de Philosophie et Lettres, Level I.”

This was a two-year bachelor of arts degree program in Louvain’s liberal arts college. There were no special programs or courses for students studying abroad here. I would be taking regular courses with Belgian students and other francophone students.

The registrar gave me a list of Level I courses for the academic year which began in early October and ended in early July. I couldn’t believe my eyes! There was a total of 24 courses for the entire academic year, the equivalent of 12 per semester back home!

The registrar gave me a condescending look and with a smirk on his face said, “Bonnes études, Monsieur” (“Good luck, sir”), and sent me on my way.

Making a friend

“Oh, lordy,” I thought as I went back to my lodgings, “What have I done coming here?”

As I dragged myself up the wooden steps to my rooms, panicky and depressed, I met a fellow tenant who occupied a flat on the third floor. He was a French student from Lille named Yves.

He introduced himself and asked me if there was anything wrong. I explained to him what had just transpired at the International House.

“Ah,” he smiled knowingly.

He invited me into his apartment to share a bottle of wine. Yves was an economics major and had just completed his first year in the master’s program. He was only a year older than me but seemed so much wiser in the ways of European academia.

“Look at your study program,” he told me, “and you will notice that many of these courses are only one-credit courses. Your major courses are the three-credit courses.”

He went on to tell me that it was absolutely necessary that I attend all my courses the first week of classes when the professors would distribute a list of required reading materials for the final exam. In the majority of cases, that final exam would be an oral exam at the end of the academic year.

“You will be alone with the professor in a room where he will question you on course content. You have the option of not attending any school-year lectures, since all lectures will be published and are available for you to purchase at the Student Union.”

I gave him a quizzical look.

“The professors don’t mind; it’s more money in their pocket, don’t you see?”

He went on to explain that there were certain courses that one needed to attend regularly, such as in math, sciences, or in my case, languages, but that I would quickly discover which ones I had to attend and which ones I did not.

I don’t know if it was because of his reassuring words or the wine, but I soon started feeling much better. He warned me, however, that this system put a lot of responsibility on the student.

“A question of self-discipline,” he told me.

It was very easy to go astray, or to become lax in one’s study habits; there were too many distractions and opportunities to wander off the studious path, particularly for foreign students. He had seen too many of his classmates fall victim to bad study habits.

Yves gave me good advice that I always followed. He admired my pluck for trying to rough it with regular francophone students. He told me that my French was quite good, and as I seemed to be a serious student that I would be just fine.

He became somewhat of a mentor and a true friend.

A riot to start the school year

Since I had the month of September to do as I wished, I decided to get to know the country better by traveling throughout Belgium.

I returned to Louvain at the beginning of October for the new academic year. My train was filled with other students. The next several days saw trains, buses, autos, and mopeds disgorging thousands of students into Louvain. The city doubled in population in no time at all.

The last weekend before the start of classes I could see from my balcony the main avenue packed with so many students that all vehicular traffic had ceased.

That Friday evening things got quickly out of hand.

The movie theater opposite the main street where I lived was overcrowded with boisterous students. I could hear loud rumbling sounds emanating from the building. The candy ladies of the movie house who usually walked up and down the aisles selling sweets from their baskets stood in front of the entrance and did not dare walk the aisles that night.

The local police were mobilizing at both ends of the main avenue, supported by Brussels police with paramilitary vehicles, including water cannons.

When the movie-goers came out, some of them inebriated and shouting wildly, all hell broke loose. Reinforced by the movie mob, hooligan students at each end of the avenue started throwing things at the police and began tearing up the cobbled-stoned avenue with crowbars, shovels, hammers — anything that would dislodge the stones, which they piled into makeshift barricades.

The town vs. gown tradition

I was horrified. I went downstairs to Yves’ apartment and told him and a student friend, André, to come and see what was happening.

As we stood on my balcony, Yves told me that the students were doing what they do each year at the beginning of a new term. It was the traditional town vs. gown confrontation going back to the Middle Ages when university towns were autonomous and self-policing.

This confrontation had gone on for centuries at Louvain with each opening school year. It was a kind of game or ritual between students and the local authorities which lasted for several days until things returned to normalcy with the start of classes. Like any game, it had its rules of engagement: students did not break shop windows or vandalize homes and businesses, and the police did not use excessive force nor strike female students or bystanders.

“Since we do not have athletic programs at Louvain, think of it as a sporting event, our Pamplona, a running of the bulls,” Yves said jokingly.

André wanted to go outdoors where the action was taking place. I gave Yves a dubious look, but when he agreed I went along reluctantly. We stood on the sidewalk in front of our building when policemen, wielding clubs and rubber hoses, came running our way, striking any young males who looked like students.

They pounced on the three of us, despite my protestations that we lived here and that we were merely observing. I got clubbed on the back and neck as did Yves, but the worst off was André. He was pummeled all over, holding tight for dear life to a nearby lamp post.

We managed to grab him and pushed him back into our resident building while fending off the blows. He was bruised and sore, cussing the police louder with each painful step up the stairs. As it was not safe to go back on the street, André spent the night with us.

I had never experienced anything like this back home.

Quiet and order restored

The tumult and mayhem continued throughout Saturday and into early Sunday morning when it tapered off and finally stopped.

On the way back from church, I noticed work crews getting ready to dismantle the barricades, clean up the debris, and repair the streets. The next day, the first day of classes, everything seemed right again. The main avenue and town square were as attractive as I had seen them when I first arrived, traffic ran smoothly, people went about their business, and students prepared for the serious work at hand.

I attended the first week of classes with eager anticipation and a degree of trepidation. It was the fear factor of taking courses in an unknown foreign environment. However, everything went smoothly. I got all the necessary information from the professors in each of my courses. I assiduously took notes, and at the end of my first week I was confident that I could hold my own with other francophone students.

The only course that gave me pause was an advanced German language course that I was taking with mostly Flemish students. Flemish-Dutch is to German what Portuguese is to Spanish. It was a struggle at times to keep up with the fast pace in this class. I did succeed in the course, but it required much more study and preparation than I had anticipated.

I found all my courses interesting, but soon realized that I could not attend a dozen courses per week. I did attend all my major courses weekly, and alternated attending the one-credit courses every other week so that I became knowledgeable about course content and what the professors desired in their respective course. Needless to say, I purchased all of their lecture notes as recommended.

Women as classmates

After taking classes for a month, what struck me was the lack of rapport between professors and students in the liberal arts college.

At PC, I was used to seeing students ask questions of their teachers in the classroom. Indeed, it was encouraged by many teachers, but not here. The professors came, lectured, and left afterwards without taking questions.

I was informed later that this was not the case in advanced degree programs or seminars where there was more give and take between professors and students. The one advantage was that the undergraduate students had the benefit of reputable scholars lecturing in their area of expertise and did not have to put up with inexperienced teaching assistants.

A great benefit to me in Louvain’s liberal arts program was the number of female undergraduate students. The program had the highest concentration of female students of any degree program at the university, upwards of 40 percent.

I had graduated from an all-male parochial high school and PC was not a co-ed college at the time. I enjoyed having young women in my classes, listening to their points of view on varied topics, the perspective and intensity that they brought to any discussion, the intellectual bantering after class that continued in the student cafeteria or in restaurants.

This interaction is what I missed the most when I returned to PC for my final year.

Finding other Americans

For foreign francophone students, the International House was like a second home. Since Louvain had a large international student body, it was nice to have a place where students from various countries and backgrounds could meet and exchange cultural views and ideas.

The house was well-run, with managers organizing all sorts of events around geographic nationalities and entities. National clubs existed to bring students together where they would partake in cultural “soirées” for the benefit and enjoyment of other students and their guests.

Of course the largest contingency of French-speaking students had their own clubs. I was surprised and pleased to learn that there was an American club. I was informed that about two dozen Americans were enrolled in the medical school, while others were enrolled in various graduate programs, and some like myself in the undergraduate liberal arts program.

The International House provided names and available local addresses of these students along with their mailbox number. That is how I came to know other Americans at Louvain, in particular those also enrolled in the liberal arts program. We remained friends throughout the academic year, often meeting to share notes, ideas, and to boost each other’s morale.

A difference in relationships

The most popular meeting place was a huge student cafeteria several buildings down from my apartment.

It was open every day from 7 a.m. to 11 p.m. One could buy a continental breakfast for only a quarter. Other meals were quite inexpensive. Most students liked to gather there, especially between classes.

Seating arrangements were casual and somewhat improvised. I was keen on making friends with Belgian students, but I was frustrated in the slow pace of personal contact. In the first month of classes, most of them kept their distance.

Sometimes in the classroom or while seated in the cafeteria I could hear nearby students whispering “C’est un Américain.”

I was told by some acquaintances that I should not impose myself on Belgian students, but rather let them come to me. This is how I met two of my best friends, Jean-François and Pierre. They were first-year students in the liberal arts master’s program, and they were popular with both undergraduate and graduate students.

Jean-François first approached me in the cafeteria and introduced himself and Pierre. They knew most of the professors and gave me good insight on them and their courses. They were the epicenter of an ever-expanding concentric circle of students that I met and with whom I became friendly.

In particular, my female classmates became much more accessible to me. They now spoke to me before or after class lectures, invited me to join their group in the cafeteria or to attend field trips which the university organized for new students. However, as a male foreign student I was made aware of certain cultural pitfalls vis-a-vis young women.

My friend Yves and others had told me that I could not casually invite a young woman out to dinner one-on-one, as this would have serious implications. It was a social way of telling any young lady that you were ready to make a serious commitment to her beyond mere friendship. That is why most students went out in groups.

I liked the friendship of female classmates and enjoyed the way some of them played on my vanity or teased me, but I was not ready for any entanglements or complications in my life.

Christmas in Italy

The Christmas season was soon upon us. I had made plans to spend two weeks traveling throughout Italy, in particular Rome, Naples, and other southern parts of the country.

Even though I journeyed by myself, it was a most enjoyable trip.

I returned to Louvain for the resumption of classes in the new year, 1963. I was anxious to see all of my friends, and they were glad to see me also. I even had a “wow” moment when some of my female classmates greeted me with a “bise,” a peck on both cheeks.

They all wanted to hear about my trip to Italy. It was a delight for me to resume my university studies under such pleasant circumstances. The new calendar year also brought new acquaintances, new academic challenges, and pleasant surprises.

I had been told by friends at the International House that it was a mark of friendship and esteem for a foreigner to be invited to meet someone’s family. In early February, Jean-François asked me to spend a weekend with his family in Brussels, and later in the month I spent a weekend with Pierre’s family in Liège. Yves asked André and I to spend several days with his family in Lille during the Easter break in April. It was an honor and a pleasure to spend time with their families. I count these visits among my most enjoyable.

Pierre was a literature major in the masters program with an interest in drama. He was a member of the university’s drama club and gave Jean-François and I free tickets to many performances in which he participated. He was a tall, handsome young man who, I noticed, turned the head of many ladies. He even performed a monologue recital of selective excerpts from Molière’s comedies for me and his family when I paid them a visit. I had told him before that I loved Molière, and he surprised me with this gift. The recital was terrific! I told all my friends about it back at school.

Visiting Belgium’s battlefields

Jean-François was a history major in the masters program. He was particularly interested in contemporary history. One day while we were together in the cafeteria, I told him that I had an interest in military history, due to our Revolutionary War and our great American Civil War. He noted that Belgium had been the location of some of Europe’s greatest battles, from Napoleon’s Waterloo to the Battle of the Bulge, to the bloody trench warfare of World War I (“In Flanders fields…”).

I told him I would like to visit these famous battlefields before leaving Belgium. He offered to take me there and give me a personal historical tour. I thanked him profusely for his kind offer.

I did not know it then, but his father had been killed as a soldier in the early years of World War II. I knew that he and his older brother had been raised by their widowed mom, he had previously told me as much. It was only when I visited all three of them that weekend in their Brussels apartment that I found out that his father had been a casualty of the war.

When Jean-François and I were alone, I told him how sorry I was to learn of the circumstances and that we need not visit any battlefields if it made him uncomfortable. He insisted that we do so as previously planned. That is how the two of us spent many weekends visiting these well-known sites.

Jean-François did everything intensely, and he was always well prepared on these visits. He was well versed and had more facts readily available than the official tour guides. What I found amusing was to see francophone visitors break away from their paid touring groups and follow along with us.

Easter with Yves in Lille

I did not venture far from Louvain during the Easter holiday except for a brief visit to Yves’ family in Lille. André and I traveled together by train. Yves had left several days earlier to make the necessary arrangements. He met us at the railway station in a large chauffeur-driven automobile. He came from a wealthy industrial family and they lived on a large estate. I had no inkling that his family was wealthy since Yves seldom spoke about them and he personally was very unpretentious. I do recall him telling me that he had two younger sisters.

André and I spent several days with the family. I do remember the sisters becoming very inquisitive during the formal dinners about myself and the U.S. in general. They wanted to know about my family, education, social status, friends, etc. They were curious about America, its vastness and ethnic composition, the major points of interest. Yves’ mother opined, somewhat gratuitously, that there wasn’t much to see in America. His father, though, was in awe of our country’s great industrial might.

During the daytime there were all sorts of activities possible, such as bowling on the lawn (French style), tennis, croquet, horseback riding, or picnics. The evening of our last day there, the family organized a party for Yves and his guests. There was a small orchestra in the ballroom where couples danced; a lavish spread of varied foods on a large table (my favorite was smoked salmon with caviar); and a large choice of the best regional wines and champagne. A veritable French feast.

After thanking our hosts, André, Yves and I took the train back to Louvain the following day.

Prepping for exams

We were now entering the crucial phase of the study period of any academic year — from-mid-April to middle or late June in preparation for the final exams. One could hear many students saying “Il faut bûcher” (“We have to work hard now”), to chop away or cram for the exams. This was true for everyone, not just the academic slackers.

We all knew that the final exams would be one-on-one with the professor in any given course. The problem was in anticipating what kinds of questions the individual teachers would ask and how we would respond. Since there were so many students taking these singular exams, the professors usually designed their questions so they could quickly ascertain how much a student knew of the subject matter at hand and give a grade accordingly.

We were told that the oral exam usually lasted about 10 minutes for each student. This was my first introduction to serious study group preparation. A group of six to eight students in the same course would get together and practice anticipating the kinds of questions beforehand. Each student in the group would take turns answering a question posed by the other students. The student would be evaluated by his or her peers not only by the answer given, but also how one answered with regard to body language, self-assurance, meaningful amplification, etc.

Each category was rated on a scale of 1-5, and the student was given feedback anonymously by the evaluators. This helped the student know his or her strong/weak points in preparing for the exam. My female classmates were very emphatic in using this approach, and I found this method beneficial for my finals.

Sometimes we had the advance knowledge of how a particular professor might posit a question. For example, in our contemporary history study group, Jean-François had told us that one would expect the professor to ask a student about Max Weber’s famous thesis on the role of Protestantism in the rise of capitalism, which a member of our study group had been asked by other students. However, commented Jean-François, the professor is more likely in that 10-minute exam span to ask for the refutations or arguments against this thesis by other historians, which presupposed that one was already familiar with Weber’s thesis.

The professor had mentioned in his lectures some historians who disagreed with Weber.

“Do not anticipate the obvious,” said Jean-François. “Be prepared for the non-apparent!”

Final oral examinations

No matter how much one prepares for final oral exams, unless one has been through it all before, it can be quite intimidating.

The university exam period ran about three weeks, from mid-June to the first week of July. All graduate and specialized degree programs had their exams in the second half of June, while all undergraduate programs had theirs the last week of June and the first week of July.

Professors reserved huge blocks of hours for these exams, and it was up to the student to register on a preferred day for any given exam and at a time of his or her choice, if available.

Long registration lists were affixed to the door of the professor’s examination room in order to sign up on a first-come first-served basis. Block times fluctuated between 15 minutes for 1- or 2-credit courses and upwards of 30 minutes for 3- or 4-credit courses.

I was told by my friends to sign up quickly for those courses in which I felt most comfortable. I signed up for my 1- or 2-credit courses as soon as possible, thinking that a mere 15-minute examination time for each wouldn’t be so bad. After introductions and polite casual conversation, that left only 10 minutes of actual questioning for the exam. The professor can’t ask too many questions in that time span, I thought.

I was so wrong! I was amazed at how much a professor was able to tell what one knew or did not know in that short amount of time. The rapid-fire questions and probing of the material were quite relentless. There was no room here for BS answers or even claim a “trou de mémoire” (memory lapse). Jean-François’ advice to expect the unexpected proved accurate. The one advantage was that the format allowed you to backtrack and amend your answer if you realized you had made a gaffe, something that would not be possible in a submitted written exam.

With each exam, I became more familiar and comfortable with the whole process. Even my 3- or 4-credit courses, which consumed a 30-minute block, went off smoothly.

Most professors would put you at ease at the start by conversing in a friendly way on other matters of a general nature. Some professors would not waste time but got right down to the business at hand, particularly if the exam also involved improvised translations of foreign texts. A few professors adopted a hostile or adversarial attitude, and the entire exam period was stressful for everyone.

While waiting your turn outside the examination room, one could see students were apprehensive pacing back and forth in the hallway. I even saw a female student leave one of the examination rooms in tears. Fortunately, I did not encounter obstacles and successfully completed all of my exams by July 6.

Leaving Louvain

Yves, André, Jean-François, and Pierre had finished their master’s degree exams in late June. Each would be sent an official diploma by mail. There was no cap and gown graduation regalia at Louvain. Many celebrated their success by planning a graduation party at one of Louvain’s finest restaurants the last weekend in June. Although I was still in the thick of exams, I was invited to join them. Female colleagues and friends were also present and everyone had a good time.

When we were alone, Yves told me that his family was rewarding his academic achievements by buying him a brand new convertible motorcar. He invited me to drive with him and André to the French Riviera for some sun and fun. The trip would be on him, he said.

Alas, I had already made arrangements with Pierre and Jean-François to spend 5 or 6 weeks in Paris before returning to the U.S. Yves was disappointed, but he understood. We spent a final evening, just the two of us, at a local bistro, recollecting the things we had done together during the academic year, including the family visit.

I told him that I was more beholden to him than he realized, how much his support had meant to me, and what a special friend he had become. The next morning I helped him with his luggage, we gave each other a final hug after promising to stay in touch, and waved goodbye as he departed for France. I had to prepare for an exam later that day. One week later, I left Louvain for good.

On to Paris

My sojourn to Paris was due to a convergence of events. I had expressed to Jean-François and Pierre an interest in spending several weeks there before returning home. I knew that it would be expensive living in hotels at the height of the summer tourist season. Pierre told me that he also might be in Paris then, since he had applied for a workshop grant for aspiring young francophone actors sponsored by France’s national theater, the Comédie Française.

After a series of interviews and auditions, he was notified of his acceptance sometime in May. We were all happy for him. Through family connections, he knew where we could rent an inexpensive apartment on the Left Bank, in a working-class section of the city.

Jean-Francois expressed an interest in joining us. He had been told by a history professor at Louvain that the Bibliothèque Nationale was offering a summer series of open seminars on the new Annales school of history and criticism. As an historian he was interested in attending these seminars, and it gave him another motivation for joining Pierre and I.

Pierre left in early July to rent our apartment and make other arrangements. Jean-François and I met him in Paris a week later. The three of us would share the rental expense, which would make more economical a longer stay. As for myself, I was planning on doing just a lot of walking and sightseeing, until I was informed by an American teacher of French from Iowa, who happened to be sitting next to us at an outdoor café one evening, that she was taking a summer course at the Sorbonne, and that I might want to check it out.

Class at the Sorbonne

I went to the Sorbonne, made some inquiries, and was told that indeed they were offering summer courses in language and literature in conjunction with the Alliance Française and underwritten by the French government. These courses were primarily for foreign teachers of French. Although I was not a teacher, I told them that I was interested in taking a literature course. Anyone who was not an actual teacher could take any of the courses on two conditions: show advanced French language proficiency and pay a registration fee for taking courses (waived if you were a francophone teacher).

The first condition wasn’t a problem since my French was now impeccable, even flawless, so much so that along with my French name the registration people thought I was a Frenchman and not a foreigner. I had to produce my American passport, which surprised them. “Ah!, Monsieur est américain!” That reaction was typical during my stay in Paris.

Even though these courses were non-credit courses, I still had to pay a fee (less than $100, as I recall). All of the courses ran for a period of 4-5 weeks, from mid-July to mid-August.

Reading modern novelists

I had enrolled in a contemporary French literature course which was held in a large classroom three days per week, Tuesday through Thursday. This gave everyone a long extended weekend to do as they pleased. The professor, a young academic, assumed that we were already familiar with most major 20th-century French writers, Proust, Mauriac, Sartre, Camus. Therefore he gave us a required reading list of fine contemporary writers, many little known at the time.

I recall him telling us that some of the most original new writers weren’t even French, though they were writing in the language. Our list included the writer of Russian birth, Adamov; the Romanian playwright, Eugene Ionesco; the Franco-American novelist born in France, Julien Green; and especially an expatriate Irishman named Samuel Beckett.

Two Frenchmen on the list need to be mentioned. Céline, whose seminal novel Voyage to the End of the Night had a huge international impact and who today is considered one of France’s greatest writers of the 20th century was little appreciated at that time.

The other was the controversial writer, Jean Genet, whose best known novel Our Lady of the Flowers was banned outright in the U.S. because of Genet’s open homosexuality and the many homoerotic themes in the novel. Reading these authors was an intellectual revelation. Although this was a non-credit course with no papers submitted or even a final exam, it was one of the better courses in my entire year of studying abroad, and the exposure to these writers served me well for future U.S. graduate work.

‘No place on earth I would rather be’

Our apartment was on the third floor in a noisy neighborhood with a constant smell of various foods. We did not mind. Although sparsely furnished, the apartment was clean, and there was a nearby Metro station which we used daily. Pierre’s acting workshop was on the Left Bank of Paris, as was the Sorbonne, but the BN, which Jean-François was attending, was on the Right Bank.

After our individual commitments we usually met around 4 p.m. at the same popular café on the open air terrace not far from the Seine River and Notre Dame Cathedral. We would sit there for several hours chatting about our daily intellectual endeavors and discoveries while drinking fine inexpensive wines.

It was exhilarating to watch the world go by, a constant stream of tourists and locals, especially the Parisian girls in their flowered blouses, swirling skirts and high-toned legs. On certain weekend nights, when twilight occurred late in the evening under a serene mix of blue, pink and orange sky, we would drink and dance the night away. It was then that I realized why poets romanticized Paris and why it seemed to me the center of the universe.

At certain moments an intense feeling overcame me, and I felt that there was no other place on earth I would rather be! Alas, I knew that this dreamscape would soon come to an end when I returned home.

Coming home

It was time for me to return home from my yearly studies in Europe. In the middle of August 1963, I made preparations to do so. I had finished my audited course at the Sorbonne, and Jean-François had finished his history seminars at the BN, while Pierre was still involved in his theatrical workshop. I bid him a fond farewell.

Jean-François said that he would help me with my luggage and accompany me to the Paris airport. I was traveling lightly then, having already sent two huge trunks of books and miscellaneous items to the Belgian port of Antwerp during my last week in Louvain. I wished to spend several days in London before returning to New England. I booked a mid-week flight, and my friend and I took a bus to the airport. Jean-François remained with me until it was time for me to board my flight to London. It was hard leaving him since he was my first true Belgian friend. We both had a heartfelt goodbye and promised to stay in touch.

When I arrived in London I stayed at an inexpensive hotel near Piccadilly and toured the city for several days. On the Sunday of that same week I took a direct flight from London to Boston, and then a connecting flight to Portland, Maine. A cousin picked me up at the airport and took me to my hometown of Lewiston. I had not told my elderly mother that I would be home that Sunday as I wished to surprise her. Oh, the joy on her face when she saw me again safe and sound after more than a year’s absence. We clung to each other for the longest time and the tears flowed freely! She organized a special homecoming evening for family and friends to come by and question me about my experiences studying abroad.

I had received some correspondence from Providence College concerning registration and housing for my senior year. I had been informed via a Western Union telegram that my trunks from Belgium had arrived in Portland, and the University of Louvain sent me an unexpected certificate of studies.

Roger Cronkhite was a fellow student at PC from my hometown. We knew each other from way back since we had graduated from the same parochial high school. He contacted me at Louvain and asked if I wanted to share a room on campus with him and another student during our senior year. If so, I needed to wire him a room deposit. I did not think much about living on or off campus at the time and I forwarded him the money.

It was only later that I realized it would’ve been better to live off campus by myself. It was very difficult for me to reintegrate into the college life that I had left behind before going abroad. The true cultural shock for me was not going abroad, but the return to PC for my final year. After being exposed to an international, cosmopolitan education and lifestyle for over a year, I could not adjust to the old college life that I had previously known. Living in limited quarters with two other students in Raymond Hall, the curfews imposed on students at the time, compulsory attendance of classes, the lack of female students, the confined physical space of a small campus, and a monolithic ideology of life’s way sent me into a tailspin and a mental depression.

I had serious emotional problems the first months back on campus, and the Dominican fathers helped me to overcome my problems with wise advice and suggestions. I shall always be grateful to them. Because of their help, I was able to resume a productive student life at PC, made the dean’s list my senior year, and was able to continue my academic career upon leaving Providence College.

Postscript

I had given all my friends at Louvain my home address in Maine. During the Christmas break in 1963, Yves sent me his condolences on the recent death of our young President Kennedy. He also informed me that he was leaving shortly for Africa to open a branch of the family business in the Côte d’Ivoire. If it prospered there, he was hoping to continue expanding in other francophone African countries.

I also heard from Jean-François and Pierre on the subject of our assassinated president. They and their many acquaintances were distraught at the turn of events. Pierre was hopeful of a promising acting career. Jean-François was undecided whether to become a teacher or to pursue a diplomatic career. Our correspondence continued for the next several years. In the last letter that I received from Jean-François, he informed me that Pierre had been involved in an automobile accident which had permanently disfigured him. He also told me that he would be soon be posted with a Belgian delegation in Puerto Rico.

I never heard from André after leaving Louvain. I returned to that old city in 1984 with my wife. It still maintained its old medieval qualities. However, there were some changes that I did not like, such as removing the old cobble stones in the main streets and squares, replacing them with black asphalt and white stripes. The old theater near where I lived was gone as were some notable restaurants. The student cafeteria near my lodgings was also gone, replaced by an inner mall of antique shops. My wife still thought the old university city beautiful and understood why I had chosen to study there. It was the highlight of my student days, and I hope to return there one more time.