Professor Christopher Berard and the Knights of the Seminar Table

Professor Christopher Berard and the Knights of the Seminar Table

By Michael Hagan ’15, ’19G

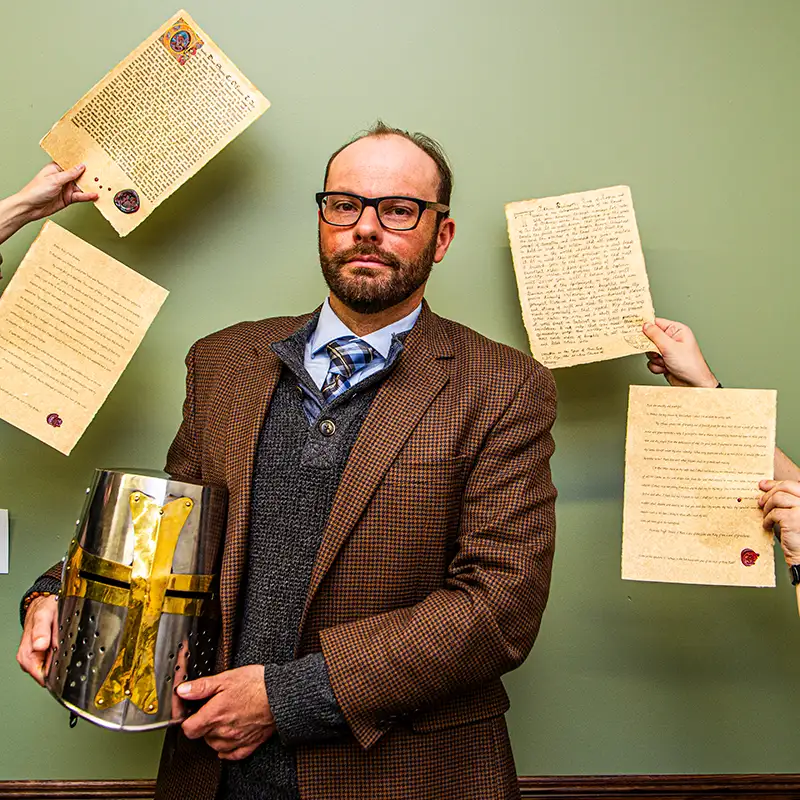

A new course offered by Christopher Berard, Ph.D. ’07, adjunct professor of humanities, introduced students to selections in translation from the massive Lancelot-Grail Cycle of Old French prose Arthurian romances (c. 1210–30), the most comprehensive and canonical version of the Arthurian legend ever written.

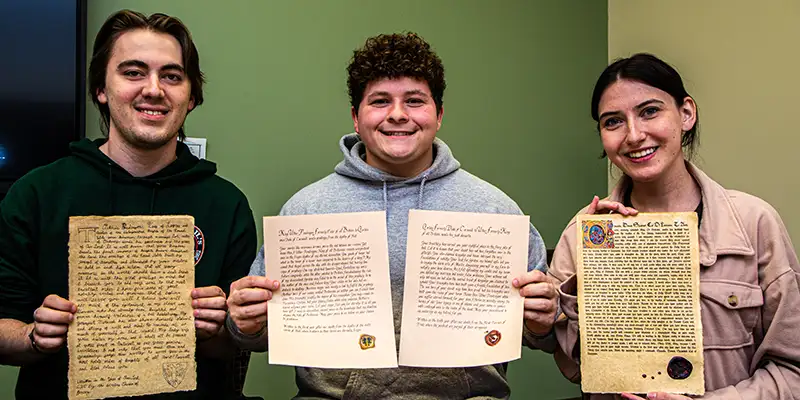

The 1.5-credit course, King Arthur: Monarch of the Medieval Imagination, culminated in a creative writing project in which students composed a mock letter according to the formal conventions of medieval epistolary documents such as public acts and private letters. Each student assumed the persona of one Arthurian character, addressed the document to another Arthurian character, and made a major plot point and overarching theme from the Lancelot-Grail Cycle the focus of the document.

The course drew from Berard’s undergraduate studies in history and English at Providence College and doctoral work in medieval studies at the University of Toronto. The course’s design reflects commitments to interdisciplinary learning and to graded work that is accessible, engaging, and memorable, in alignment with the principles and practices of Universal Design for Learning. UDL draws from cognitive science and prioritizes flexibility and multiple modes of access suited to diverse styles of learning.

“Having taught undergraduates at PC for eight years, I’ve learned that the best professors are good listeners,” Berard said. “Students want courses that strengthen reading comprehension and that develop skills of critical inquiry, textual analysis, and creativity that are valuable in just about any career. I designed this course in response to that need and to help students slow down, read, and see characters and stories from multiple perspectives.”

Berard is an instructor in the college’s Development of Western Civilization Program, known as Civ. In the first three semesters of the four-semester program, students read and study sources from across three millennia, so it can be a challenge to stay awhile in a particular period or intellectual movement.

“My goal was to apply the methods and best aspects of Civ to a particular era and its primary sources that students can engage for a full semester,” Berard said.

Alexander Lamoureux ’27, whose majors are marketing and theatre, was a student in Berard’s Civ course during his first year. When he learned about the King Arthur course, he was excited to study with sustained focus topics briefly introduced in Civ.

“I love to dig into topics I enjoy. Taking this course was my first opportunity to study medieval history and Arthurian legend in greater depth. It was a great decision,” Lamoureux said.

He hopes to adapt the stories for stage as he continues his theatre studies.

“It’s always good to have new knowledge under your belt,” Lamoureux said. “By learning the stories of King Arthur, I’ve received something very old that I can share and pass on myself. Storytelling and imagination play an important role in forming values and common bonds.”

The course’s content may seem esoteric, but Berard believes the literature of distant cultures like medieval England and France can help students understand the origins and functions of literary forms and genres in the present day.

King Arthur is a name most college students have heard but few know much about.

They might have seen The Sword in the Stone, the 1963 animated film about a young Arthur by produced by Walt Disney. They might be familiar with irreverent portrayals in Mark Twain’s decidedly anti-monarchial novel A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court or the 1975 comedy film, Monty Python and the Holy Grail. They might remember Shrek the Third, the 2007 DreamWorks Animation film in which pop star Justin Timberlake voices Artie, a teenager reluctant to be king.

Alexandra Laramee ’27 encountered King Arthur through the Magic Treehouse children’s novels by Mary Pope Osborne. The stories featuring King Arthur and other Arthurian characters and settings were her favorite. But introduction to source material rich with religious symbolism and moral questions was like encountering Camelot — the legendary castle where King Arthur resided and held court — for the first time.

“I never knew how much of the story I had been missing,” Laramee said.

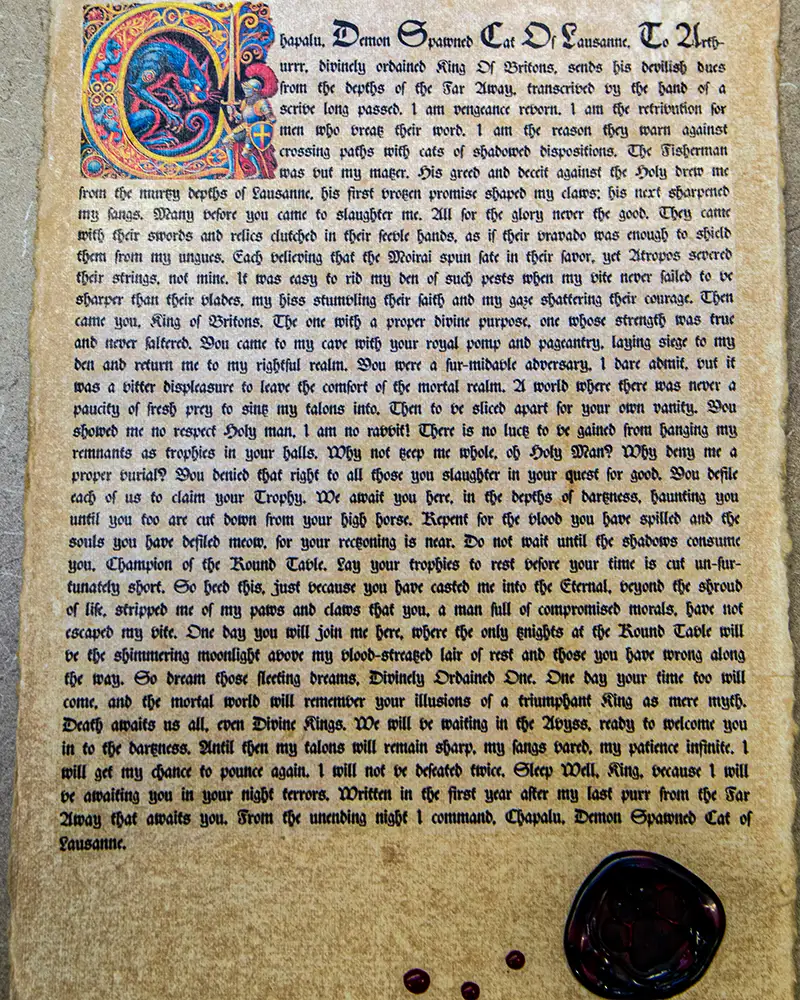

For her final project, Laramee drew from Arthur’s battle with a demonic cat. She wrote a letter in the voice of the slain cat cursing Arthur for removing its paws as trophies. A cat with human intelligence writing a letter from the beyond the grave to a living king is fantastic myth akin to other fantasy elements of the Arthurian tradition.

“The letter threatens King Arthur: If he keeps taking trophies and denying his enemies the dignity of being buried whole, he will meet them in the afterlife where they will battle again,” Laramee said.

For the visual and tactile aspects of the project, she printed her letter on transfer paper before ironing it onto a parchment-like sheet. She used red and black wax melts and a stamp to make a seal with the appearance of a bloody paw print.

Arthurian source material is different from modern adaptations, spoofs, and references. The content is as serious as it is fanciful, and the manuscripts are themselves historical artifacts. Medieval studies is a demanding scholarly field that requires proficiency in Latin and in old forms of vernacular languages that are largely unintelligible to modern readers and speakers.

Berard, who majored in history as an undergraduate, was introduced to the field by Constance Rousseau, Ph.D. ’80, professor of history. As an instructor and mentor, Rousseau guided Berard to graduate studies at the University of Toronto, a prestigious center of scholarship in medieval studies where she had earned her doctorate. At PC, the two have taught together in Civ, and they wear matching Toronto red and black doctoral gowns at Academic Convocation and Commencement.

In Toronto, Berard took courses in Paleography, the study of ancient scripts and abbreviations; Codicology, the study of the tools, materials, and techniques used to produce medieval books (codices); and, Diplomatics, the study of the formal conventions and content of official and non-official historical documents. He also studied Medieval Latin (c. 500–1500) Old French (c. 850–1350), and Middle English (c. 1150–1500).

“Many people don’t realize that the medieval studies field involves such rigorous study of and work with languages,” Berard said.

The interdisciplinary field shares similarities with other areas of study in the humanities, especially classical studies, which Berard and other scholars describe as the “older sibling” of medieval studies.

“The stories of Arthur and his companions ask questions still relevant today. For instance, Arthur’s mysterious lineage prompts questions about the true nature of fatherhood,” Berard said. “Sir Antor — also known as Hector — is Arthur’s father because he raised him, even if he is not his biological father.”

If a real King Arthur existed, scholars believe he would have lived around 500 A.D., before the Anglo-Saxon consolidation of power in much of former Roman Britain. But the first mention scholars have of Arthur dates to 820 A.D.

“Arthur is more historically distant from the High Middle Ages than George Washington is from our lives today,” Berard said. “Knowing so little about him — not even knowing if he really existed — helps to remind us of his true significance as a shining light of a distant golden age in medieval minds and imagination.”

Berard is grateful to be able to share his love for and expertise in Arthurian legend, its context, and its reception history, and he is delighted by students’ enthusiasm for the course and the sometimes-unexpected ways they have fun with it — like the time Lamoureaux brought a replica medieval combat helmet to class.

“These are different stories in different style of storytelling than students encounter in most courses. They are fascinating, they invite us to engage cultures and traditions unique and distant from our own, and they can be downright fun,” Berard said. “I am proud of the ways this course facilitates experiences similar to the best and most formative experiences I had as an undergraduate at Providence College.”