Hannah Albright ’18: Taking on ‘Frankenstein’ at the Library of Congress

By Chris Machado

It could be the best-known science experiment ever put to page — Victor Frankenstein’s creature in Mary Shelley’s celebrated 1818 novel, Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus.

It’s probably no surprise that Hannah Albright ’18 (Malden, Mass.) is interested in this science-fiction forerunner. After all, she graduated from Providence College as an English major with a minor in evolutionary biology and ecology.

In fact, her interest is so profound, she completed a senior thesis research project that probed the depths of Frankenstein — from Shelley’s book to subsequent plays to the classic 1931 Universal film, Frankenstein. What she discovered was that Shelley’s 200-year-old story tackles important questions still being asked today.

“What does it mean to be human? When does science go too far? What is a woman’s role in society?” said Albright, who also is a French minor. “It was an obvious reminder that we have always been concerned about similar issues, and that Mary Shelley, who was around 18 years old when she was first writing the novel, had such an amazing and unexpected effect on our world today.”

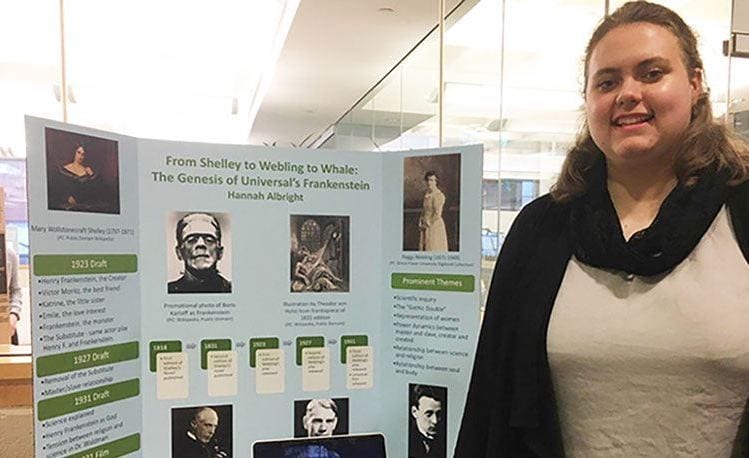

Albright presented her project, “From Shelley to Webling to Whale: The Genesis of Universal’s Frankenstein,” at the College’s 9th annual Celebration of Student Scholarship and Creativity in April. The annual event showcases the scholarly, creative, and service work that PC students conduct on campus, in the community, and around the world. This year’s showcase featured 106 projects presented by 229 students.

The idea for Albright’s research project developed when her adviser, Dr. Bruce Graver, professor of English, approached her to assist him with a project. Graver had been in contact with a descendant of Peggy Webling, a novelist and playwright who adapted Shelley’s book to the stage.

“I read the Webling play and realized how radically different it was from any version of Frankenstein we know,” Graver said. “Hannah told me sometime last fall that she wanted to work on Frankenstein. So, I asked her if she’d like to work on the Webling material, and she seemed quite excited.”

Albright said the notion of working on these lesser-known works “immediately interested” her because she loved Shelley’s book, and she knew the effort would produce original research.

“There hasn’t been any major analysis of these plays in the past. My main goal was to give Webling’s work its due because she’s been often overlooked,” she said. “I also was interested in learning the history behind why the 1931 movie was so different from the book, and these plays were the answer.”

Albright found support from the College’s Undergraduate Research Committee, which awarded her funding to travel to the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C., where she was able to view original manuscripts written by Webling and her editor, John Balderston.

She explained that the third draft in the series of plays was only available to read in the Library of Congress, where she spent two days in the manuscript reading room — poring through microfilm “using one of the old machines with the hand crank.”

“Due to a copyright on the script, I was not allowed to take photos,” she said. “So, for about 10 hours, I basically typed up the script into my notes, along with my own commentary of the handwritten edits and condition of the pages. It was very exciting to be able to do this type of archival work.”

Working with Webling’s scripts from 1923 and 1927, Graver said Albright “put together what amounts to the untold story of how Shelley’s novel was transformed” into the 1931 film.

Albright’s research highlighted significant differences among the various versions — the book, plays, and film — of Frankenstein. For instance, Boris Karloff’s famous movie portrayal of the creature was of a man with bolts in his neck. In Shelley’s book and Webling’s plays, this wasn’t the case. Other differences between the portrayals that were highlighted in Albright’s research include the removal of certain characters from the Shelley novel, as well as an emotional softening of the creature.

As evidenced by her educational path throughout her PC career, Albright admits to having varied interests. With librarians for parents, a love of literature has been engrained in her throughout her life. So, to have the freedom to delve deeply into a classic work of fiction, and then to be able to dig even deeper, proved to be “greatly rewarding.”

Those rewards might be even greater than Albright could have imagined. Graver said Albright’s research was so good that he intends to incorporate it into an academic paper and list her as a co-author.

“I’m so proud of the work I was able to accomplish, especially because I created an actual product to show people,” said Albright. “If the opportunity is available to other students, I would recommend doing research like this. It allowed me to learn and then, in return, teach others in a very different and exciting way.”