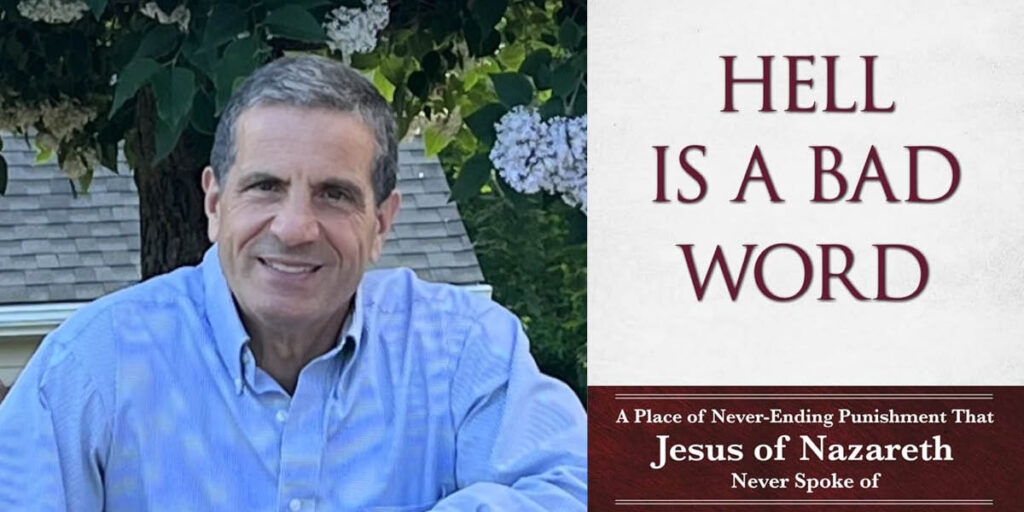

Three-time PC graduate Michael Bahry’s book examines Jesus’ teachings about hell

By Michael Hagan ’15, ’19G

As a trained carpenter who spends his days serving the poor and teaching about God’s grace, justice, and mercy, Michael Bahry ’91SCE, ’17G, ’22G lives out the universal call to imitate Christ in more ways than one. Through diligent study of biblical sources and Christian tradition, his scholarship helps readers and students navigate some of Christianity’s most challenging questions about death, resurrection, and eternity.

Bahry is adjunct professor of religious and theological studies at Salve Regina University in Newport, Rhode Island, and the author of Hell Is A Bad Word: A Place of Never-Ending Punishment that Jesus of Nazareth Never Spoke Of. The book is an expansion of the thesis Bahry wrote while pursuing his second master’s degree at Providence College, this one in biblical studies.

Bahry first enrolled in a theology course through PC’s School of Continuing Education in 1985 with no intention of completing a degree. The instructor was Rev. James F. Quigley, O.P. ’60, a longtime faculty member who has taught topics in theology and ministry at Providence College, Our Lady of Providence Seminary in the Mount Pleasant neighborhood of Providence, and the Pontifical North American College at the Vatican in Rome.

“Michael has been a friend for decades now, and we get together frequently. I’ve seen him grow intellectually, in virtue, and as a family man,” Father Quigley said.

Motivated by a desire to better understand his faith and guided by Father Quigley as he got “into a groove,” Bahry relished hours in the classroom and savored assigned readings. As the semester drew to a close, he decided to increase his course load. In 1991, he graduated with a bachelor of arts degree in religious studies and history.

While he was a student, Bahry and his wife, Missy, married, with Father Quigley attending their wedding, and became the parents two children. After graduation, Bahry became executive director of PC’s Physical Plant and acting vice president of facilities. He held the role for five years before joining a construction company.

In 2011 he foundd Bahry Building Company, which specialized in constructing and renovating schools and other public buildings in and around his hometown of East Providence. Bahry took pride in building suitable spaces for learning, but his persistent curiosity drew him back to such spaces as a student, too.

In 2015, while running his construction business, Bahry enrolled in the Master of Theological Studies Program at PC, focusing his study on early church history. He had been baptized in the Maronite Church, which is in full communion with the Roman Catholic Church but celebrates some liturgies in Aramaic, the language of first-century Judeans. Bahry was captivated by the words of Jesus; he imagined hearing them in the language in which Jesus would have spoken them. Though a member of Catholic communities for most of his life, Bahry tries to attend Maronite liturgies at least once each year.

Bahry graduated from the MTS program in May 2017, but he returned to the graduate theology program the following January to pursue a master of arts degree in biblical studies. That degree required him to complete and defend a thesis, an extended work of original scholarship. It was an opportunity to confront a question with which Bahry, like many Christians, wrestled most of his life: How can a loving God condemn human beings to eternal torment in hell?

“Many Christians have great anxiety about hell and the idea that people they love who died outside of the faith will be tormented there for eternity,” Bahry said. “Never-ending punishment is an incomprehensibly harsh sentence that seems inconsistent with teachings about God’s mercy. Without minimizing sin, I think one can fairly ask if the punishment fits the crime.”

For five years, Bahry studied biblical texts and languages with particular attention to passages related to the afterlife. He noted 109 instances of the term “hell” in the Douay-Rheims Bible, an early modern English translation of the Latin Vulgate which is itself translated from Aramaic, Greek, and Hebrew.

“It is often said that no one ever spoke more about hell than Jesus,” Bahry said. “My research challenges that idea.”

He found the term “hell” to be translated from words including “sheol” and “hades,” terms referring to a realm of the dead, impossibly distant from the living world, in ancient Hebrew and Greek tradition.

“These Greek and Hebrew destinations of the dead are not places of punishment reserved for the wicked — everyone goes there when they die. In the Old Testament canon, divine punishment comes in life through disease, war, or other calamities,” Bahry said.

In other instances, “hell” is translated from Gehenna, a valley southwest of Jerusalem where the Old Testament claims kings Ahaz and Mannasah of Judah sacrificially immolated their children in attempts to win divine favor. The prophet Jeremiah pronounces the Lord’s curse on the valley, calling it “the valley of slaughter.”

“If you don’t consider where terms come from in the Old Testament, you really won’t understand their meaning in the New Testament. Why does Jesus refer to Gehenna, a place associated with fire and the exile to Babylon? I’m not certain. This allusion certainly does not rule out punishment in the afterlife,” Bahry said.

He formed Mercy Publishers to publish his book, expanded from his thesis, in 2023.

Ian Levy, Ph.D., professor of theology and former director of PC’s graduate theology program, was a member of the committee that reviewed Bahry’s thesis.

“What strikes me about Michael is his dedication to and seriousness about his work,” Levy said. “Old and New Testament sources, perspectives from the early church, systematic theology — his thesis and the book that came of it draw from all facets of his studies.”

Bahry considers uncertainty a necessary experience in theology and biblical scholarship. He admires Hans Urs von Balthasar, the 20th-century priest and theologian who saw eternal punishment as a real possibility for human persons, but also believed it was a Christian’s duty to hope that all will be saved in defiance of presumption that any will be damned. Hope as a theological virtue is not blind optimism or niaivete, but confidence in the promises of Christ. Bahry argues that the eternal punishment of those who die with mortal sin or lacking faith is a particular interpretation of biblical sources, not an unambiguous teaching of the gospel.

“It’s not that I am afraid to claim something unorthodox if it’s what the sources make clear,” Bahry said. “I’m just uncertain. My thesis is that God is merciful, and we really don’t know how he will dispense his justice in the end.”

A lifelong Christian, Bahry was always confronted with the mystery of eternity and questions about heaven and hell. In 2018, when he began teaching in the Rite of Christian Initiation for Adults program at Our Lady of Loreto parish in East Providence, helping adults receive the sacraments for the first time, he felt called to refine and publish his scholarship.

“When I started teaching RCIA, I was given a copy of the Baltimore Catechism, which teaches much on the afterlife and eternal torment. This was a hard teaching for new Christians and for me — one that faith demanded I continue to study,” Bahry said.

The gospel is meant to challenge, but Bahry emphasizes that it is above all good news and an invitation to discipleship.

“In scripture, it’s hard to tell when Jesus is talking about the afterlife. It’s unclear. Preoccupation with metaphors for divine justice can overshadow what is clear — that we are to live every day loving God and neighbor,” Bahry said. “We are all the rich man living in comfort as Lazarus suffers. We are all the people in error in each parable. The gospel challenges us: What are we to do with that?”

His response to the challenge includes prayerful study, teaching others about Jesus and Christian life, and volunteer leadership of his local nonprofit, Fifty-Three: Five, which provides material assistance and fellowship to neighbors in need in the Providence area. The organization’s name references a passage from the Book of Isaiah referring to the “suffering servant,” which Christians regards as prophesying the life and sacrificial death of Jesus.

Through his community service work, Bahry collaborated with the Most Rev. James T. Ruggieri ’90, the new bishop of Portland, Maine, who previously was pastor of St. Patrick Church in the Smith Hill neighborhood of Providence and St. Michael Church in South Providence.

The COVID-19 pandemic required Fifty Three: Five to suspend several of its ministries, so Bahry and fellow volunteers focused on food assistance. They have delivered more than 25,000 lunches to people in need since 2020.

“I was once on my way to leading a chapel service for a group of homeless Providence residents, and who do I see but Father Ruggieri rushing down the street with bags of groceries to share with the poor. He had already been appointed bishop,” Bahry said.

“Michael is an example of how to be a husband, father, and now grandfather. He’s an example of what it means to live the faith as a believing Catholic Christian man,” Father Quigley said.

Bahry’s daughter holds a doctorate in psychology and studies autism. His son is a special education teacher and athletics coach. Bahry and Missy have a two-year-old grandson.

“It has been one of God’s greatest gifts to me to watch my grandson grow,” said Bahry. “I was working so much when my children were this age.”

In 2023, Bahry left construction to focus on teaching theology at the college level and running his nonprofit. He speaks publicly about his faith every month at a homeless shelter. He remains grateful to the faculty of the graduate theology program for modeling prayerful and rigorous study, and most admires his professors’ humility, which is “essential when approaching scripture and questions like these.”

“I had to get over a lot to do this. I had to overcome being an introvert. I had to stay disciplined and wake up early to write. But it’s been worth it,” he said.

“The mercy of God is that important.”