May 21, 2015

Intellectual hospitality: the heart of teaching at PC

BY AURELIE A. HAGSTROM, S.T.D. ’85

Although not a Dominican myself, I say this as one who has taught theology for nearly 12 years at the College and whose formal theological training came mostly from Dominicans at PC and at the Pontifical University of St. Thomas Aquinas (Angelicum) in Rome.

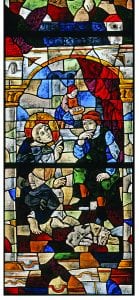

Intellectual hospitality was modeled by St. Dominic himself when he used dialogue as an approach to ommunicating the truths of the faith. While traveling through Toulouse in 1203, he encountered an innkeeper who was a member of the Albigensian heretical sect. St. Dominic stayed up all night with him, talking about the truths of the Catholic faith. By dawn, St. Dominic had won the innkeeper back to the true faith.

This famous incident illustrates that the Dominican approach to theology and teaching is dialogical; that is, it seeks to proclaim, persuade, and convince its opponents and respondents, rather than silence, defeat, and conquer them. In this famous story, St. Dominic demonstrates a certain kind of “intellectual hospitality” in the context of meaningful dialogue, which is fundamental to teaching and learning.

Another Dominican example would be St. Thomas Aquinas, who also employed a dialogical model in his teaching and his theology. In his Summa, he used the teachings of a Jew, Maimonides, as well as a Muslim, Averroes. In fact, the philosophy of the pagan, Aristotle, which was an integral element in Aquinas’ project, was largely available to him only through these Jewish and Islamic scholars.

In this dialogue, St. Thomas was not afraid to find truth even from people with whom he did not agree philosophically or theologically. This sort of confidence in seeking the truth wherever it may be found is based upon the conviction that truth is one, and that there can be no contradiction be-tween the truth that flows from faith and that which comes through reason. This bold search for truth in a dialogical methodology, modeling a kind of “intellectual hospitality,” is a challenge for anyone who desires to engage in teaching and learning in the Dominican tradition.

Over the years, I have tried to think of my classroom as a place of hospitality. As the professor, I act as “host” and “set the table” for my students with my lectures, homework assignments, and discussions. The students are the “guests” who are welcomed with their own perspectives, experience, views, and academic interests. In this interchange of hospitality, there can be, at times, a surprising reversal of roles wherein I become the guest and my students can act as host. Intellectual hospitality means that the perspective of my students could easily supplement and perhaps even correct my own work or transform my self-understanding.

This openness to sharing and receiving claims to knowledge and insight gives the classroom, in my experience, a certain dynamism that prevents the course from becoming stagnant or simply routine. Good hospitality can generate stimulating “table talk,” and here is where the academic enterprise can become a transforming event for both host and guests — professor and students.

This is what happened that night in Toulouse, and this is what can happen in the classroom, around the seminar table, in the lab, or anywhere that students and professors gather to seek the truth — Veritas — in all of its complexity and beauty.

Dr. Aurelie A. Hagstrom ’85 is an associate professor of theology at PC and the faculty resident director of the Providence College/CEA Center for Theology & Religious Studies in Rome.