Kareem Abdul-Jabbar discusses fight for justice and equality at fourth annual MLK Convocation

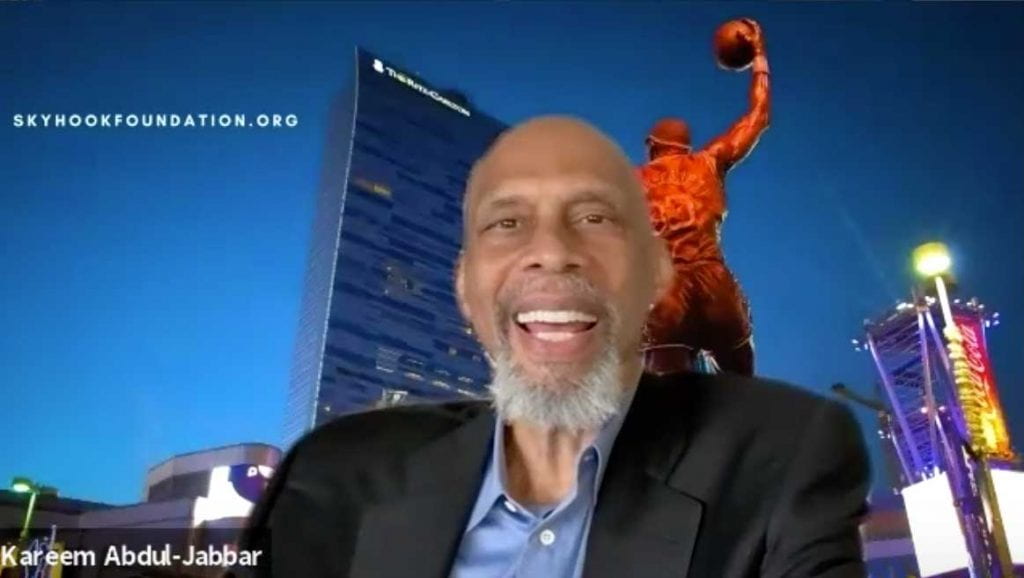

Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, athlete, political activist, and advocate for education, was the featured speaker at Providence College’s fourth annual Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Convocation on Feb. 11, 2021. Abdul-Jabbar, the NBA’s all-time leading scorer, six-time champion, and only six-time MVP, was presented with the nation’s highest civilian honor, the Presidential Medal of Freedom, by President Barack Obama in 2016.

Following an introduction from Dr. Sean F. Reid, provost and senior vice president for academic affairs, and a welcome and prayer by College President Rev. Kenneth R. Sicard, O.P. ’78 & ’82G, Abdul-Jabbar spoke to PC students, faculty, staff, and alumni via Zoom. The discussion was moderated by Julia Murphy ’21 (Pittsfield, Mass.), a political science major, member of the women’s softball team, and president of the Student-Athlete Advisory Council, and David Duke Jr. ’22 (Providence, R.I.), a business major and member of the men’s basketball team.

A transcript of the conversation follows:

Julia Murphy ’21: David and I are both student-athletes, so we have a real appreciation of all that Kareem Abdul-Jabbar has accomplished, both on and off the basketball court.

David Duke Jr. ’22: More than 50 audience members submitted questions for us tonight, and we have narrowed that list down to just a few due to time constraints, but we want to thank everyone who provided questions all of which helped shape tonight’s discussion.

Julia Murphy ’21: We’re so excited to begin this conversation, so let’s get started. Michelle Napierski-Prancl ’24P, the mother of a current PC student, asked this question: “You write that you met Martin Luther King Jr. when you were in high school, so can you tell us what it was like to meet Dr. King at such a formative time in your life?”

Kareem Abdul-Jabbar: Well, for me, it was very much a surprise to meet Dr. King. It was between my junior and senior years in high school, the summer of 1964. I was taking part in a mentoring program in my hometown in New York City. It was designed by Dr. John Henry Clark, a black historian and sociologist, and he was friends with Dr. King. He asked Dr. King to come up and address participants in this mentoring program and Dr King obliged him. I’d say there were about 200 or 300 kids involved in this program and it was the first time that I had a chance to get close to Dr. King.

I was in a journalism workshop, so the people that put on the event gave me press credentials and let me cover the event with the press corps that was following Dr. King around all the time. He’d been voted man of the year in 1963 and the press paid attention to everything that he was doing at that time, so it was very special to get to speak to him. I got to ask him a question after he addressed us. I asked him if he thought the program would be a success, and he said that it already had become a success, because already the kids participating were thinking about how to make their community a better place.

It really challenged me. At that time in my life, I was more a fan of Malcolm X, because Malcolm X was more militant in his attitude and he gave a lot more comfort to the people who wanted to fight back against the racist bullies that were giving the civil rights movement such a hard time. But Dr. King’s example really helped me understand that the long-term challenge was to peacefully and non-violently effect change. And the best way to do that is through reason and discourse. Dr King really enabled me to make good choices just by his presence, and I’ve felt that there’s a debt there that I owe him throughout my life, because his example has really been the one that has led the way.

David Duke Jr. ’22: This question is from Kate Kennedy ’92, president of PC’s National Alumni Association: “Where do you place this past summer’s protests and this year’s energies by the Black Lives Matter movement in a historical context, and how do we keep up the energies in the face of such strong headwinds, as we saw at the Capitol insurrection?”

Kareem Abdul-Jabbar: I think that once you get a better perspective on what we’re going through right now, you won’t see any difference between what we’re trying to do now and what Dr. King was doing back in the ’50s and ’60s. There’s no difference; it is actually the same civil rights movement. The same one that I got drawn into when I was in high school is the same set of events that you guys are trying to participate in now. When I look and see what people like Colin Kaepernick and others have tried to demonstrate to the world, there’s no change, the objectives are exactly the same — freedom, justice, and equality for all American citizens regardless of race, ethnicity, national origin, religion, all of those things, none of that means anything, it’s the content of our character. That’s what we have to focus on and that’s the direction that we have to go in.

Julia Murphy ’21: Our next question is from Sammy Gonzalez ’06: “Given how long you have stood against the unjust treatment of minorities in America, are you more or less hopeful we will finally see equal treatment of minorities in our lifetime?”

Kareem Abdul-Jabbar: Well, you know, it all depends on what you mean by our lifetime. My granddaughter might see a lot more of it than I might see. Things sometimes go backwards, so we have to be cautious, and we have to always be ready to take advantage of any opportunities to move forward. That’s an absolute necessity. So, we focus on what makes sense and how we continue to make the progress that we need to make in order to effect change.

David Duke Jr. ’22: This next question comes from Dr. Ted Andrews ’01, a faculty member in history: “Compared to other major sports leagues, the NBA has been at the forefront of social and racial injustice initiatives over the last few years. What do you think are the next steps, the most effective, actionable items that the NBA can take to support this mission moving forward?”

Kareem Abdul-Jabbar: The NBA has done a great job of giving the players free reign as to what they want to deal with. Adam Silver, our commissioner, is really sensitive to all of these things and has not tried to hold back any of the players from expressing themselves. It’s allowing everybody to make the choice as to whether or not they want to be out front with the things that they’re concerned about, or if they want to hang back. Some people don’t want to take the chance. Some of the people who have been involved in demanding change have had some negative consequences — some that we know about, like Colin Kaepernick, and a lot that we don’t know about. We’ve got to give everybody the opportunity to make the moves that they want to make when they want to do it and just try to be supportive and have them take a wise approach to how they talk about the things that they want to talk about.

I also should give out a shoutout to the WNBA. One of the players in the WNBA helped a young man get free from an unjust conviction and it took her quite some time and a lot of effort to get the criminal justice system to be responsive to this type of injustice. It goes from one end to the other in terms of how the example is being copied and reused by various groups to effect change. I see that as a good thing.

Julia Murphy ’21: As an athlete, I can say to that is just so amazing to see professional athletes using their influence to take such a firm stand against injustice. I think that is just so important for us to see and, as you said, support, and that ties in perfectly to our next question. This was submitted by Nick Sailor ’17, former men’s soccer captain and currently the director of education and training for the Office of Diversity, Equity & Inclusion. “This newer wave of athletes is recognizing the power of their voice in regard to social injustice. What advice would you give our athletes on how to utilize their voice and platform for social change?”

Kareem Abdul-Jabbar: I would just advise patience, and make sure you know what you’re talking about. And the last thing, don’t give in to expressing so much about the things that make you angry that you come across as being angry, because anger turns people off. And it’s a righteous thing that these things make you angry, you want to respond, but you can’t respond with anger, you have to respond with common sense, and you have to approach people with some respect for the fact that, hey, they might be new to the whole situation. I remember when the film came out about Rodney King, several white people said, “Our police departments don’t act like that,” and I said, “No, no, no, are you going to believe your eyes, or are you going to believe these lies? Are you going to believe what your eyes tell you? Look at the film.” More and more of these films have come across to the point now that people understand what black Americans have been experiencing for too long.

David Duke Jr. ’22: I agree with what you said about not letting your anger affect the responses to issues or anything you want to speak out about. That ties into this next question, from Sarah Soule, associate director of career education and professional development. She asked, “Can you speak to the relationship between peace and anger on our pathway to dismantling systematic racism?”

Kareem Abdul-Jabbar: We have to have our goals to be peace, but in trying to achieve a peaceful end, we will encounter a lot of things that make us angry. We can’t let our righteous response of anger get to the point where it ruins our ability to communicate. That happens too many times. It’s something that people just slide into. We have to be aware of that and be cautious. Remember that the people that you’re trying to talk to might be totally new to the situation and not understand what the dynamics are. The fact that you can explain that will definitely have the most positive impact, when you take that approach.

Julia Murphy ’21: Communication is key, especially communicating with those we don’t necessarily agree with, which is also a great segue into this question, which was submitted anonymously, “Over the last few months, I’ve noticed that people are not disagreeing on politics or policies because we’re disagreeing on reality. If we, as Americans, can’t even agree on reality, what is the best way to move forward?”

Kareem Abdul-Jabbar: We have to try to appeal to everybody’s logic and their ability for critical thinking. Critical thinking is the only thing that will enable us to define the truth from some of the things that people try to use to sway the argument. We can’t let people use lies and fiction to secure the arguments. We have to go with the truth, and if we can do that, if we have the patience to approach people and use that patience to finally get them to understand what the facts actually are, maybe we’ll be successful. You never know, but that’s what you’ve got to try.

David Duke Jr. ’22: This next question was from a member of the Class of 2022: “How can we as young people continue Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s legacy and create a global community of unity, compassion, and dignity?”

Kareem Abdul-Jabbar: In order to complete Dr. King’s vision, all you have to do is keep an awareness as to what the problems are, where are we failing, what is keeping people from achieving their goal. If you take that approach, you’ll come upon the answers. As you uncover what those issues are. So just having honest approach to what the issues are, hopefully we can agree on what the facts are and the direction.

Julia Murphy ’21: Shifting gears a bit to some more basketball talk, Ryan Mongno ’20 asked, “Who are the best role models in the NBA today?”

Kareem Abdul-Jabbar: You know, I’m biased. Lebron James has done a great job as an athlete and as a concerned citizen. He’s taken a whole school system back in Ohio and is sending all these kids to college. That’s incredible. He could be on an island someplace counting his money — he’s got a lot of it to count. He could be just concerned with that, but he cares about the community that he comes from. Here in southern California, he’s done a great job trying to keep people’s awareness at a certain point in speaking to the issues, so I got to say that I like Lebron. But I don’t want to single out just the people that are the most popular and well known, because the efforts of everybody really are able to effect change, so instead of just focusing on the superstars that are doing that, I’d like to just call attention to the guys that are maybe not as well known, but still doing what they need to do to effect change in their communities and where they’re from.

David Duke Jr. ’22: I think a big part of that is what you said earlier. The commissioner’s very sensitive to those things and allows those guys to have the confidence to speak up when they feel a certain way about any of these issues and not feel like they’re being held back or will be punished, or fined. This next question comes from my coach, Bob Walsh, who asked, “What strategies can we use to make all of us more comfortable having direct conversations about race?”

Kareem Abdul-Jabbar: I think what we need to do is to be able to speak about the things that happen and the things that have happened. A lot of the things that have happened in America make a lot of Americans uncomfortable, especially white Americans who are not aware of how bad things have been at times. So sometimes you have to take a little bit more time. It’s not a thing where you’re going to tell them, “I don’t like you for what happened 150 years ago.” That’s not what we’re doing. Or we have to point to things that have happened 150 years ago, 50 years ago. There are times that were very embarrassing for our country, but we’ve gotten past them somehow or the other, by communication. So, we just have to find that way, to speak the truth. If we can accept the truth and change things so that the truth gets to be one that treats all people the same way, well that’s progress.

Julia Murphy ’21: As athletes we can probably all agree that a lot of our moments of most significant growth have come from the moments where we’ve been most uncomfortable. I think the same can probably be said for conversations around injustice and racism. We have to let ourselves get uncomfortable if we want to have that growth and move forward, so I definitely appreciate that sentiment for sure. Rene Orquiza, assistant professor of history, and Jim Paquette ’92 both submitted versions of the same question. This is a personal favorite of mine: “What advice would 73-year-old Kareem Abdul Jabbar give to a 17-year-old Lew Alcindor?”

Kareem Abdul-Jabbar: I would probably tell the 17-year-old that he doesn’t need to listen to the 73-year-old. I’ve been through my trials and tribulations. Keep an open mind. The thing I try to tell people is “knowledge is power.” The more you can accumulate the better off you’re going to be. You’ll have the power to make good decisions and take things where you want to take them. I’ll stick with that one.

David Duke Jr. ’22: I have a question from Bob Highland ’80. He provided a great story and a question. He says, “Kareem, my grandparents remember you fondly as in 1965 you were being recruited by Coach Joe Mullaney and PC while you were at Power Memorial, and they recall you going to St. Pius Church across the street from campus and you sat in front of them. They say that was the only time in St. Pius in over 50 years that they couldn’t see the priest celebrating Mass. Do you recall your visit and meeting some of the All-Americans at Providence at that time, like Jimmy Walker ’67 or Mike Riordan ’67?”

Kareem Abdul-Jabbar: You know, I played against Jimmy Walker when I got into the NBA, but I played against Mike Riordan in high school. My freshman year we played his team. I remember some of the guys on this team, Bob McIntyre and Ken McIntyre, they went to St. John’s, Mike ended up at Providence, and they beat my team my freshman year and went on to lose to La Salle Academy for the (New York) city championship. That was 1962. And then from ’63, ’64, ’65 my Power Memorial team won the city championship. I also played against Mike when I was a rookie and he was playing with the Knicks. They beat the Milwaukee Bucks before they went on to beat the Los Angeles Lakers for the Knicks’ World Championship in 1970. I don’t know if he was on the ’73 team or not. I also played with Ernie DiGregorio ’73. He tried out for the Lakers. He was there for a little bit. Those are the guys from Providence that I remember.

Julia Murphy ’21: Now we have Mullaney Gym, which is named after Coach Mullaney, where David and the Friars have been playing this season, so a nice little PC connection we have there.

Kareem Abdul-Jabbar: I saw a number of PC teams play in the Holiday Festival (in New York City). I saw Vinny Ernst ’63 play. They had a very good team. They were contending.

Julia Murphy ’21: Our next question is from Brian Kennedy ’19. He asks, “How do you build the beloved community in your day-to-day life, obviously drawing on inspiration from one of Martin Luther King Jr.’s key teachings?”

Kareem Abdul-Jabbar: You build the community by accepting people for the content of their character. That’s what Dr. King was referring to, and not having biases or prejudices that enable you to treat people like you shouldn’t be treating them. Being open minded and accepting people. Looking for the best, that’s how we should approach people. Looking for the best, hoping that they’re not about the worst that humanity can be. I think that’s how we should go about it and that’s how we’ll build the Community that you speak of. That’s a goal that all of us should be seeking to make come to reality.

David Duke Jr. ’22: This next question comes from Jack Manning ’22: “What is the most important lesson you learned on the basketball court that you apply to all that you do in your life?”

Kareem Abdul-Jabbar: When you talk about the lessons on the basketball court, I have to go back to my college days playing for Coach (John) Wooden at UCLA. One of the things that he always used to beat us up with was, “Failing to prepare is preparing to fail.” I think he stole it from Ben Franklin, but he wore us out with that, and it makes a lot of sense. You know all the things that I’ve wanted to do and accomplish, if I don’t have the fundamental preparation totally taken care of, I’m not going to get as far as I want to get. I’ve become a perfectionist as I’ve gotten old and cranky and I want to see things happen the right way, so that’s how you do it.

Julia Murphy ’21: This next question is from Ryan Grace ’23. He says, “You are one of the biggest names in NBA history, and it is so admirable to see you use your platform and faith to advocate for crucial change regarding topics such as racial and justice and COVID-19. We see so many people who have your status use fame to advertise products they probably don’t use and stay silent when exposed to such critical movements. What is the downside to advocacy, and why do so many of your peers seem afraid to speak out? Is there a reason for their silence?”

Kareem Abdul-Jabbar: Yeah, I think there’s a reason for their silence. I think the obvious thing that can happen is what happened to Colin Kaepernick. He stepped forward. He was indulging in nonviolent protest and was prepared to do his job, but he still lost his job. Fortunately, he was able to sue and get some recourse, but those things can happen. So, you’ve got to give everybody the latitude to see if they dare risk being an activist and possibly confronting some people with something that they might try to retaliate (against). You can’t let that deter you, especially if your cause is righteous. You have to be willing to take that risk.

Julia Murphy ’21: We have time for one final question, and it touches on your answer a few minutes ago. We all have role models and for many of us who play sports, those role models are coaches. I know David had asked a question submitted by one of his coaches, but can you tell us about the lasting impact of your relationship with John Wooden?

Kareem Abdul-Jabbar: Coach Wooden really talked it like he walked it and walked it like he talked it. It was a great inspiration to us. He didn’t ask us to do anything he didn’t do. He got his degree. He was All-American as a player, he’s in the Hall of Fame as a coach. He just showed us how to do it, and he told us that the best thing we could do in our lives is to learn how to be good citizens, good fathers, good husbands. That really was what everything was all about, and a lot of people took that to heart. If you look at the graduation rate of the guys who played for him, you see that he did a very good job making us understand what it was all about and getting us out the door with that that degree in our back pocket.