The Last Word: The poet in me

By Patricia Slonina Vieira ’75

We were herded into the cavernous basement of Harkins Hall. We sat on wooden folding chairs, straining to hear the echoing instructions delivered by department heads. This was freshman orientation circa 1971 and I was among the first class of “coeds.”

My immediate concern was selecting an academic major. All else — schedules, professors, credits — depended on that choice. I loved history and politics, harboring a dream to be the country’s first woman president. But teaching history seemed like the more practical path.

When the session ended, I headed against the crowd to seek out the director of career services.

“I am thinking of majoring in history and then teaching,” I shouted over the din as he bent down from the stage to hear me.

He scowled. “You’ll never get a job — too many teachers!” He paused, probably noting my confusion. More kindly, he asked, “What do you like to do? What are you good at?”

I had long considered my skill with words a gift I received to compensate for a congenital heart condition that kept me out of gym classes and in the library. “I like writing and I’ve won a few essay contests in school …,” I began. He seized the clue, commanding, “Then be an English major. You can do anything with that.”

And that is how the arc of my life began its bent toward the writing life. But it took me more than 40 years — and a poignant message from my alma mater — to embrace the one word that describes my lifelong affinity for words.

My English Department advisor was not a tweedy professor, but a woman just a few years older than me. Jane Lunin Perel, MFA ’15Hon. was beginning her teaching career in those heady days of turmoil on campuses across the country. She described herself as the “exotic other” — a female, Jewish, bohemian-like poet hired as one of the first women faculty members at our conservative, Catholic college.

Drawn to her orbit like a moth to light, I took every possible class with Jane. A cautious introvert, I absorbed the rays of daring and possibility that whorled from her center. Under Jane’s instruction, encouragement, and guidance, I began to develop and refine my writing voice. She taught me how to look and listen to the sights and sounds others missed.

I experimented with words and line endings. I attended poetry readings in the Wooden Navel, listening always with eyes closed to see the worlds created with words. I learned to read poetry aloud with the cadence that brings life to letters on a page. I visited an unorthodox Catholic commune with upperclassmen from the student literary magazine, the Alembic, who merged their poetry with deep spirituality. I became editor of that magazine and believed every observation could be transformed into a line of poetry.

And then I graduated — time for the real world. I married, survived two open-heart surgeries, and delivered three healthy babies. My first daughter’s middle name was chosen in dual homage to my late father — whom she would never know — and to my mentor, Jane Lunin Perel.

My writing took a utilitarian turn — employee newsletters, recycling instructions, letters to the editor, press releases, and web content, to name a few applications. Jane’s formative influence lingered and we maintained warm contact. With sporadic cultivation on my part, poetry continued to thrive. My scribbled scraps accumulated in books and storage boxes.

I directed the annual poetry competition that honored the late Galway Kinnell, a Pulitzer Prize poet who shared my Pawtucket, Rhode Island, origins, with Jane graciously serving as a judge. When the U.S. poet laureate promoted “Favorite Poem” readings, I coordinated one in my town — and read one of Jane’s poems. I entered poetry contests, often sending new poems to Jane for critique. And two of my daughters asked me to write and read a poem at their weddings.

Through all those years, when people asked about my profession, I would answer, “I’m a writer.” No finer distinction seemed necessary.

Then I received a fundraising mailing from PC, asking me to consider a bequest. Was it time for that already? On the verge of discarding it, I saw a handwritten note. “Jane is featured here and she mentions you. I thought you might enjoy seeing it.”

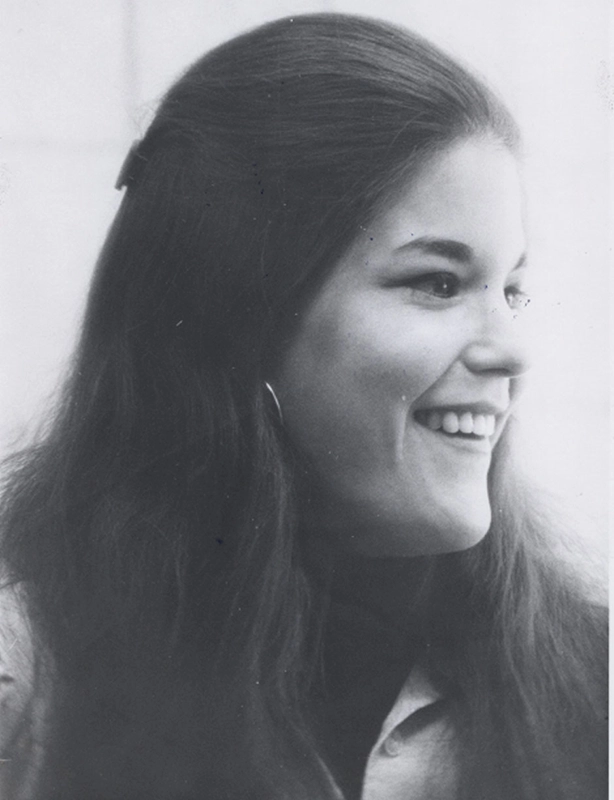

Marking the 40th anniversary of the Class of 1975 was a familiar image — the “triumvirate” photo depicting the first women to serve as editors of The Cowl, the Alembic, and Veritas. Inside, I read that Jane was retiring and would receive an honorary doctorate at the coming commencement, a well-deserved honor. In a list where Jane recalled her fondest memories, the first entry read: “Patricia Slonina Vieira … a marvelous young poet.”

My life lens shifted in a moment of recognition. I am a poet. I have always been a poet. No matter what kind of writing I do for personal satisfaction or professional success, that writing does not define me or my world view. The poet in me does that.

If I had not pushed forward to that stage and asked a perceptive stranger to guide me, I might have taught history (though it’s doubtful my presidential ambitions would have been realized). But what would my life have been without Jane’s nurture of the poetic spark she saw in me? Who would I be today? Even with a poet’s insight, I cannot imagine how different that outcome might have been.

I once read, “Don’t ever let your gift just become your job,” and have gratefully avoided that snare, even though writing has dominated my career. More than 50 years ago, two people recognized a gift in me and one became a beloved mentor. I now understand all the years since in a new way: It is the poet in me who protected the gift.

Patricia Slonina Vieira ’75 was a member of the first graduating class to include women, which celebrates its 50th anniversary this spring. A writer, editor, and poet, she resides in Cumberland, Rhode Island.