Living through History: Michael P. Sullivan ’88

By Vicki-Ann Downing

History is all around, if you know where to look for it.

Michael P. Sullivan ’88 graduated from Providence College with a degree in history, then backpacked through Europe. He brought along a classmate, William M. Frates ’88, and a book, Black Lamb and Grey Falcon, Rebecca West’s account of her travels through Yugoslavia before World War II. On a rambling walk through Bosnia Herzegovina, then one of six Yugoslav republics, Sullivan was captivated by the romanticism. He felt he had traveled back in time.

It was an appealing prospect for a history major. At PC, Sullivan ran for the varsity track team. He studied Russian and Spanish. In WDOM’s studio in the basement of St. Joseph Hall, he hosted a political talk show with Kevin M. O’Shea ’89. He put his artistic talents to work as graphics editor and political cartoonist for The Cowl. The Development of Western Civilization Program introduced him to philosophy, ethics, and decision-making.

Bosnia charmed him. People spoke about the 1389 triumph of the Ottoman Empire over the Serbs as if it happened yesterday. As Peter Maas wrote in his book, Love Thy Neighbor, only running water and the hum of the refrigerator reminded you it was the present century, Sullivan said. You felt you were 500 years in the past, sitting in a dark hovel, drinking Turkish coffee or plum brandy, listening to stringed instruments, hearing the hypnotic language.

It was the beginning of a lifelong interest in foreign countries.

Since May 2014, Sullivan has worked to defend human rights in the midst of violent conflicts on the edges of Eastern Europe. It is not his first time in a war zone. Sullivan served as rule of law director with the U.S. State Department in Afghanistan from 2010-2013. He worked on language used in the new Iraqi constitution in Baghdad in 2005. When war flared in Kosovo, he traveled there as a human rights reporter. He’s joined eight State Department delegations to monitor democratic elections in Bosnia, Serbia, Ukraine, Kosovo, and Belarus.

“You get used to being in a place where there’s a need and where you can be of assistance,” said Sullivan. “Once you get involved, it’s really difficult to stay away for too long. Part of traveling and working in war zones is that you live through history. I’ve always had a strong sense of where I was, and a sense of wonder about what it was like there in the past.”

He brings top credentials to the mission. Sullivan earned a master’s degree from the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy at Tufts University in 2000 and then studied international comparative law at Northeastern University Law School, where he interned at the oldest law firm in Thailand and at the U.S. Attorney’s Office in Boston. Through the U.S. State Department’s Antiterrorism Assistance Program, he has lectured foreign military intelligence officials and defense policymakers on ways to apply human rights in times of crisis.

Humanitarian workers usually point to a life-altering moment that prompted them to leave the sidelines and enter the action. For Sullivan, it occurred when he was 12 years old, at home in Needham, Mass., watching the NBC miniseries Holocaust. Years later, he was similarly moved by the ABC documentary Ceausescu’s Orphans, about conditions in Romanian orphanages. He decided he needed to find a way to be involved.

“I had no real plan, but opportunities have a way of appearing,” Sullivan said. “I’m in a position now where I can tell a good story as to how I planned all this out. But the more I think about it, the more I realize that you have a big-picture idea of what you want to do, and things seem to fall into place if you remain aware.”

Bosnia was at war in 1995 when Sullivan discovered a New Hampshire-based charity, Nobody’s Children, which helps children left homeless by conflict. He took time off from work, flew to Croatia, traveled inland to Bosnia, and hiked four hours to the Nobody’s Children refugee camp, where he presented himself as a volunteer. The camp was set up in railway cars on bombed-out tracks. Sullivan was sorting foreign aid donations when he heard the live radio broadcast of the signing agreement ending the conflict.

In 1998, while studying at Tufts and working as a researcher at the Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University, Sullivan attended a lecture by Physicians for Human Rights, an organization that monitors breaches of medical neutrality around the world. When the lecture ended, he approached the presenters and offered to spend his winter break working for them in Kosovo as a human rights reporter.

It was an unusual vacation. Sullivan arrived in Kosovo in January 1999 for a one-month stay just as the Serbian leader, Slobodan Milosevic, declared Physicians for Human Rights persona non-grata. Monitors discovered the bodies of 45 ethnic Albanians in the village of Racak, a massacre that became the turning point of the war, prompting NATO intervention.

A local Kosovar doctor was Sullivan’s driver and translator. He was given a satellite phone — “You needed to be up on a mountain to get reception, which would draw too much attention, so I never took it out of the box” — registered with the local police, and stayed out of sight as much as he could, conducting interviews in backrooms of cafés where government security personnel rarely ventured.

“It was a very dark time there, very intense,” said Sullivan. “The Serb military police were heavily armed and wore balaclavas on the streets. People were really shaken and waiting for what seemed like an imminent attack.”

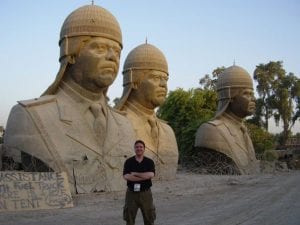

In 2005, he spent an intense five months in Baghdad working with the National Democratic Institute for International Affairs on drafting the Iraqi constitution.

“In Baghdad, you were always in danger,” said Sullivan. “There were explosions all the time, and if you were on the roads, it was a constant concern.”

When he traveled, it was in a convoy of mud-splattered cars that looked ordinary but had heavy-plated armor underneath. The vehicles drove in different directions, but their drivers were in constant contact by microphone. The goal was to create the illusion that there was no security around them, when in fact they were protected on all sides by heavily-armed SUVs.

“You’d be sitting in the back seat and the drivers would start providing grid coordinates and code names of the streets,” said Sullivan. “They were keeping you in a bubble. The cars didn’t really look like they were together, but if another vehicle seemed like it was coming up too fast and could be a threat, a car in your group might slowly move and get in the way. We moved that way for quite a while.”

Sullivan spent three years in Afghanistan with the State Department as rule of law director for Regional Command South in Kandahar. His job was to lead a team working with the legal system — courts, prosecutors, judges, police, and prisons — to help it conform with international law and support the population.

He lived in storage containers on military bases. The security situation was similar to the scene in the movie Zero Dark Thirty, where an informant is waved through a gate, exits his car, then refuses to remove his hands from his pockets as guards become increasingly panicked, Sullivan said. Most of the time nothing would happen, but the soldiers were always prepared.

He always left the base accompanied by a platoon-size Personal Security Detachment.

“They would have everything timed down to the last minute as to how you were to proceed out the gate, where you were going, what route you were taking, what support there was going to be along the way, and what the latest was on IED implants, because vehicles were hitting IEDs all the time,” Sullivan said.

In 2011, Ghulam Haider Hamidi, the reform-minded mayor of Kandahar city, was killed by a suicide bomber. Hamidi had previously worked as an accountant in northern Virginia. Friends and family had urged him to leave Afghanistan for the United States, but he would not.

Sullivan did not think about leaving, either.

“If they can’t leave, why would I leave? The very fact that I’m from outside means I can be of help. I’m their conduit — their imperfect conduit — to government services and military assistance.”

When he completed his service in Afghanistan in 2013, Sullivan received several honors from the State Department, including the Superior Honor Award. At his 25th PC reunion, he was presented the Personal Achievement Award from the Providence College National Alumni Association. He edited two volumes on human rights law and humanitarian law for the American Bar Association while awaiting his next opportunity.

In his experience, war zones “are not so different from here, except things are blowing up,” said Sullivan. “Obviously, at times of shelling, there’s a crisis, but when it slows, life quickly gets back to normal. It’s not too long after a shelling where you’re having to figure out what you’re going to be eating for dinner and if there’s a TV show on you want to watch. Life does go on.”

Sullivan is working on peace and security issues in Eastern Europe. It’s an area of relative calm, but one that saw some of the worst tragedies of World War II. The Auschwitz concentration camp is four hours away. He walks regularly amid reminders of contributions to international law at the Nuremburg trials and through the United Nations’ Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

None of this is lost on him.

“This part of the world bleeds history,” Sullivan said.