Moments of Grace: Dr. Grace ’62 reflects on his Providence College history

By VICKI-ANN DOWNING

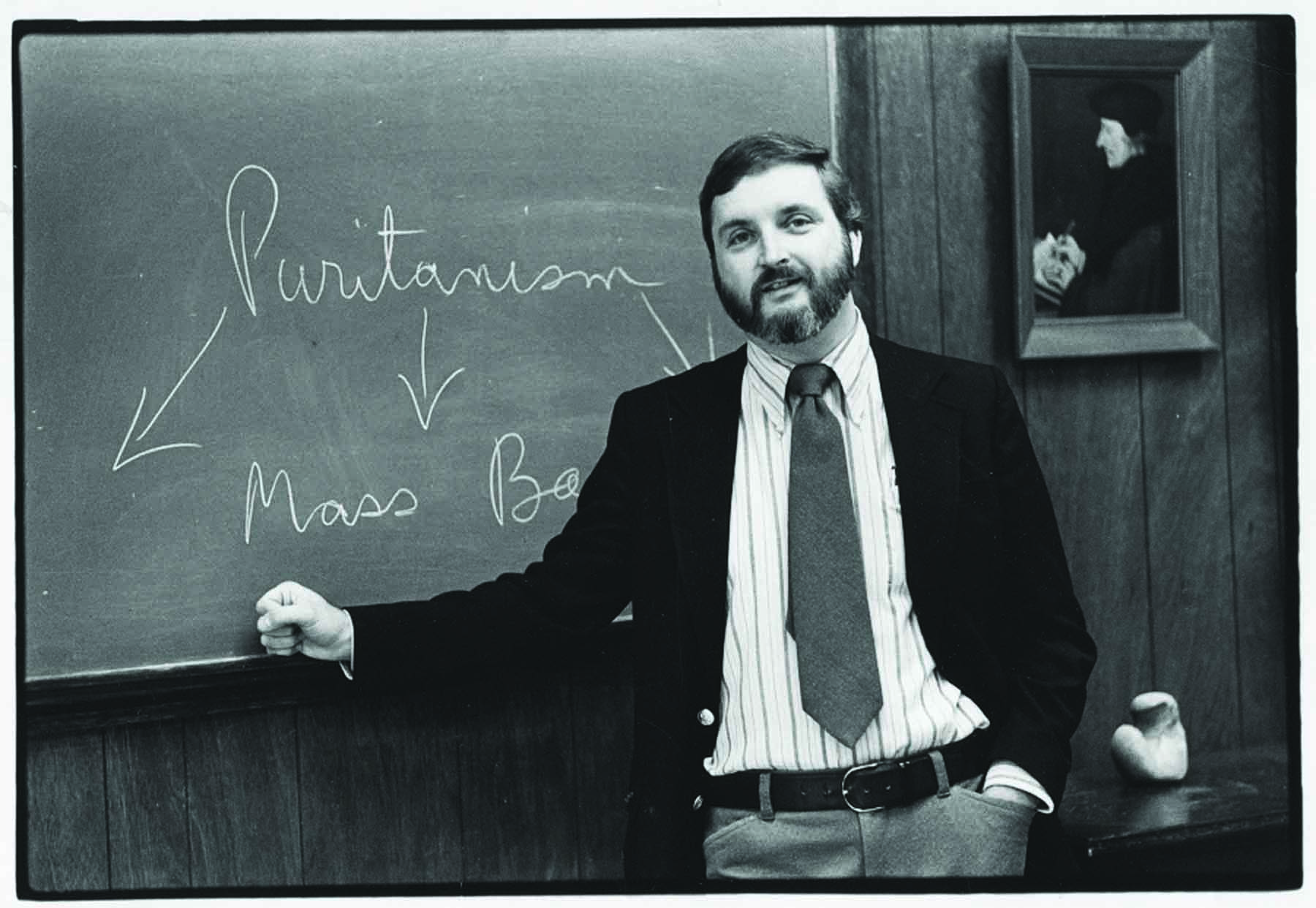

Dr. Richard J. Grace ’62, professor emeritus of history, has been at Providence College for more than half its history. He arrived in 1958 as a student in the year-old Liberal Arts Honors Program, and except for three years studying for a Ph.D. at Fordham University, has been here ever since.

Grace was a colleague of such venerable professors as Dr. Brian M. Barbour, Dr. Rodney K. Delasanta ’53, Dr. Rene E. Fortin ’55, Dr. Mario R. DiNunzio ’57, and Rev. Paul van K. Thomson ’86Hon. He was hired in 1965 by College President Rev. Vincent C. Dore, O.P. ’23 and has served under five of 12 PC presidents: Rev. William Paul Haas, O.P. ’43; Very Rev. Thomas R. Peterson, O.P. ’51 & ’85Hon.; Rev. John F. Cunningham, O.P. ’50; Rev. Philip A. Smith, O.P. ’63; and Rev. Brian J. Shanley, O.P. ’80.

Grace directed the Honors Program from 1970-1987 and chaired the history department from 1994-2000. Since his retirement in 2014, he has continued to teach a seminar in history to honors students. His recent book, Opium and Empire: The Lives and Careers of William Jardine and James Matheson, was published in 2014 by McGill-Queens University Press.

For PC’s centennial, Grace was asked to write a historical essay about the College’s past 25 years for a book that will be sold in the College bookstore next spring. (The history of the College’s first 75 years, From the Beginning: Celebrating 75 Years of Values that Endure, was written by the late Dr. Donna T. McCaffrey ’73G, ’83Ph.D., and ’87G, retired professor of history. It can be read online at centennial.providence.edu/pc-history.)

Grace and his wife, Madeleine, reside in Swansea, Mass. They are the parents of Marianne Grace Aguiar ’02, Benjamin Grace ’05, and Elizabeth Grace Heath ’09, who is the wife of David L. Heath ’09 and the mother of the Graces’ first grandchild, Samuel.

Here, Grace shares memories of his six decades at PC. Some were taken from “Last Lecture: An Epilogue,” a presentation he gave at his retirement.

Learning to teach

In his early days as a professor, Grace learned to teach by observing colleagues.

“Team-teaching was the climax of my education, as opposed to graduate school,” he said.

After classes, professors shared lunch in Alumni Hall cafeteria.

“Whoever showed up took part in the conversation, which might consider Reformation theology or Aristophanes’ plays or the poetry of John Donne — whatever had been treated in class on a given day,” said Grace. “The conversation could as easily shift to baseball trivia.”

“That just happened,” he said. “Every generation has its own cultural environment. This was part of the generation of teachers I belonged to.”

Back then, fewer professors held Ph.Ds., and many were hired before their dissertations were complete. Once they were, and the professors had demonstrated scholarship, they generally were awarded tenure.

Pressures on young faculty are greater today, Grace said. They all have Ph.Ds., and they are young, with most at PC hired after 2005.

“My wife and I had some young faculty to dinner at our home on a Friday night,” said Grace. “They teach history, language, and business, and they are from New Zealand, Chile, and Poland.”

Adapting to change

The lecture format once was the staple of teaching. Today, the model is often smaller, seminar-style classes that encourage student engagement. Classrooms have moveable tables and chairs.

“A lecture can be linear — you can follow an outline,” said Grace. “In the seminar room, you can never predict how the discussion is going to go.”

The faculty’s introduction to computers “began with the on-off switch” in workshops in Harkins Hall in the mid-to-late 1980s and evolved from there.

“In the 1960s, if you wanted to show a film, someone set up the projector and screen for you, or you used a Kodak Carousel and showed slides,” said Grace.

Today, a professor’s iPad can be connected to Apple TV.

“During my sabbatical year at Cambridge University in 1993, I needed printer access. The woman who assisted me said she would give me email access, too. ‘What the heck is email?’ I thought. ‘Who would I send it to?’”

He keeps up with changes in technology, because “you don’t want to look like a dinosaur.”

Finding a voice

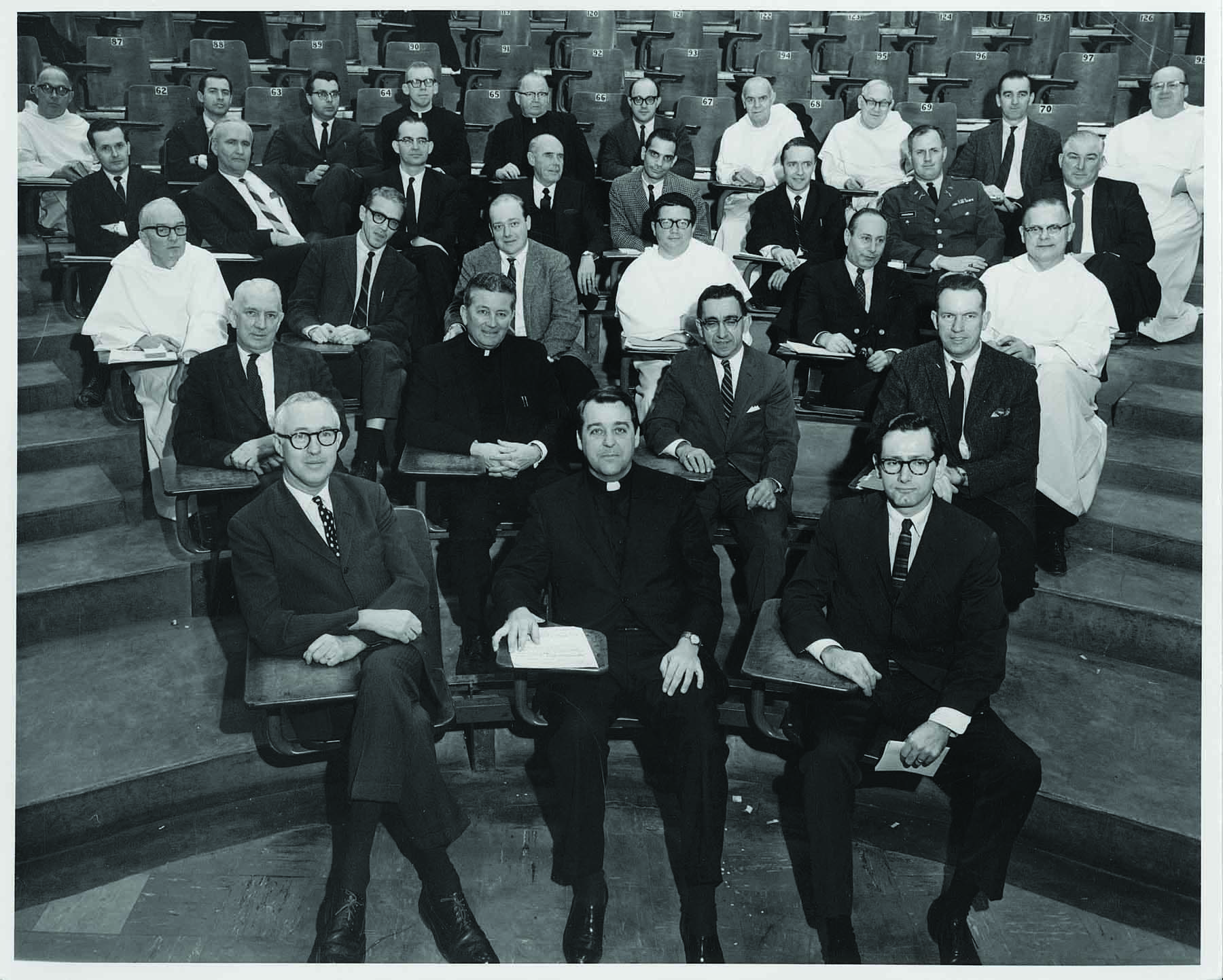

Faculty found their voice through the establishment of the Faculty Senate in the 1960s. Grace remembers the origins.

He was dining on Federal Hill with colleagues on Nov. 9, 1965, when the lights went out. The Northeast blackout left 30 million people from New Jersey to Canada without electricity.

“We all got into one car and came back to campus,” said Grace. “We sat down in the Alumni Hall cafeteria, which had emergency lights. We started talking. I was just a rookie, so I was listening. There was a suggestion of bringing the American Association of University Professors to campus. Some said we should talk to Father Haas about it. So they did. And that eventually led to the creation of the Faculty Senate.”

Faculty leadership was displayed in 1968 when Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated. Professors decided to establish a scholarship for students of color and agreed to contribute a portion of their salaries by payroll deduction to get the effort going.

Eventually, the College took over the scholarship, and today, the Martin Luther King, Jr. Scholarship Program is a major factor in increasing diversity among the student population. Students of color make up about 16 percent of the student body.

Standing with students

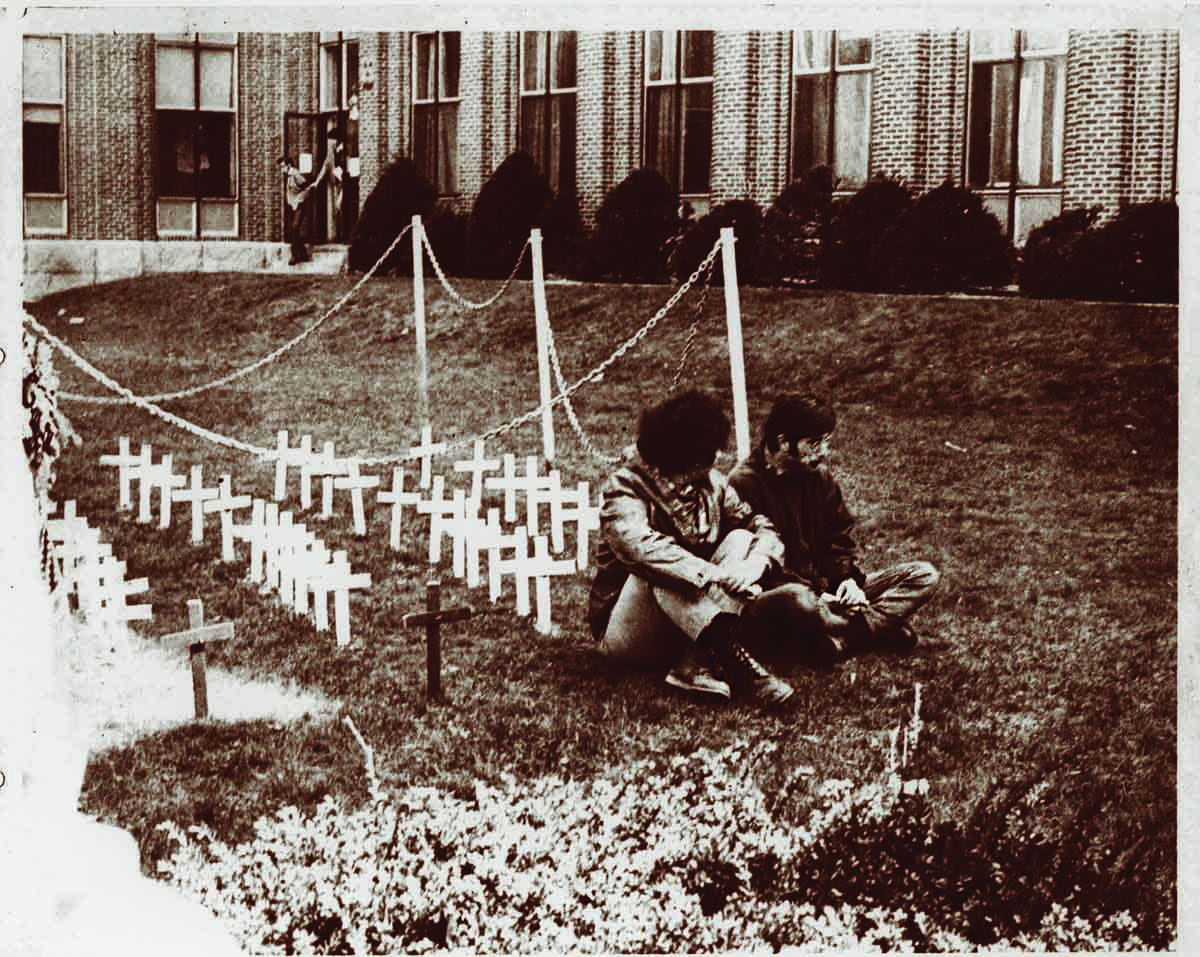

The escalating war in Vietnam that divided America united faculty and students. In October 1969, PC participated in the nationwide Moratorium to End the War in Vietnam with teach-ins outside Aquinas Hall and a march to the State House for a rally.

“We walked out the gates and down River Avenue to Smith Street, where we met the Rhode Island College contingent,” said Grace. “There were about 1,000 of us. We linked arms. Folks even came out of the bars along Smith Street to see us.”

In May 1970, when four students were killed by the Ohio National Guard at Kent State University, colleges across the country ended the semester early. At PC, student organizers were ready to call for a strike. The Faculty Senate met in emergency session in Aquinas Hall Lounge and approved legislation that ended the academic year early.

“I remember the tensions in that room, with President Haas sitting near the podium and signing bills as they were passed to him by the president of the Senate, DiNunzio,” said Grace. “And I shall always remember the faces of the students pressed up against those floor-to-ceiling windows, waiting to see whether the faculty was with them or not.

“We were.”

Welcoming women

When Father Haas was president in the late 1960s, the College began considering whether to admit women as undergraduates.

Faculty were asked: Was it financially necessary, and was it a good idea?

“I said yes to both,” said Grace. “It’s one of the best things that happened to the College.”

The first women arrived in September 1971, a time when young men were still being drafted.

“The men had a very different perspective than the first young women who were arriving,” said Grace. “It was a contrast between the new brightness of the arriving women and the cynicism of the guys, who were fearing being drafted and sent to Vietnam. The arrival of women did a lot to improve the atmosphere.”

Women were the majority in the Honors Program almost immediately, Grace said. By 1978, they outnumbered men in the undergraduate population, a trend that has continued ever since.

Mourning a great loss

On the morning of Dec. 13, 1977, newlywed Grace was awakened in his Smith Street apartment by a neighbor who told him that a fire during the night in Aquinas Hall had killed seven female students. Three more died later from their injuries.

On the morning of Dec. 13, 1977, newlywed Grace was awakened in his Smith Street apartment by a neighbor who told him that a fire during the night in Aquinas Hall had killed seven female students. Three more died later from their injuries.

Grace, who was the Honors Program director, opened the honors room to faculty seeking a place to gather. It was housed then in Stephen Hall, now the Feinstein Academic Center.

“It was the closest retreat from the terrible scene outside,” said Grace.

He likened it to “a whole group of faculty engaged in a dreadful seminar, with just one question: ‘Why?’”

“I remember it like a tableau of faculty who had to deal with the immediacy of the question of suffering. We were used to talking about that question around the Wilson Table, but it was usually in a work of literature. Now it was just outside the door, and we weren’t very good at addressing it. And we kept asking God to give us an answer, and He was silent that morning.”

It was a watershed moment in the history of the College. Some have called it the birth of the PC “family.” Grace credits the College president, Father Peterson, who moved into Aquinas Hall when it reopened and lived alongside students as a reassuring presence.

Remaining Catholic

When Grace was a student, and for 25 years after, it was taken for granted that PC “was a Catholic college and was always going to be a Catholic college,” he said. “Then, attitudes changed as the world was secularizing.”

In the early 1990s, the College struggled with the question of how to retain its Catholic identity “without becoming a fortress religious school — very protective, in a confrontational way, against the rest of the world,” said Grace. “It was a tension. Should only Catholic faculty be hired to teach? How do you achieve that with non-discriminatory hiring?”

“One of the ways that emerged over the course of years was for the Dominicans to assume a more deliberate role in preserving the Catholic identity,” said Grace. “I think they’ve done a very, very good job of that.”

Under Father Shanley, the Office of Mission and Ministry was established. Today, about 2,400 students are involved in activities through the Campus Ministry Center in St. Dominic Chapel.

“I’m not afraid of PC becoming Catholic in name only,” said Grace. “But the attention to Catholic identity has to be more deliberate than when I was a student here.”

Honoring the humanities

The Ruane Center for the Humanities opened in 2013 primarily as a home for DWC, the Honors Program, and the English and history departments. Its seven seminar rooms are dedicated to Grace, Delasanta, Fortin, DiNunzio, Barbour, Father Thomson, and Father Cunningham — all Honors Program directors or DWC professors.

The center’s dedication, on a beautiful afternoon in October 2013, is one of Grace’s favorite PC memories. The keynote speaker, historian David McCullough, spoke about the importance and value of a liberal arts education.

“It was like he gave the College a big hug,” said Grace.

During the ceremony, Grace and DiNunzio were asked to stand and be acknowledged by the crowd.

“The applause rang in my ears like the Bells of St. Clement’s and seemed to go on for a long time,” said Grace. “I could only say ‘thank you’ to all the various corners of the assemblage, for I had temporarily forgotten all the other words I know.”

This story originally appeared in the Fall 2016 issue of Providence College Magazine.