Music degree puts maestro Dr. Troy Quinn ’05 at center stage

By Vicki-Ann Downing

Dr. Troy Quinn ’05, the maestro who conducts symphony orchestras, has shared a concert stage with Mick Jagger and plays Star Wars soundtracks while driving.

Music in all its forms is Quinn’s passion. A voice major and theatre minor at Providence College, Quinn is music director and conductor of the Owensboro Symphony Orchestra in Kentucky and the Venice Symphony in Florida. He lives in Los Angeles, where he teaches conducting on the faculty of the Thornton School of Music at the University of Southern California.

“I have a unique perspective because I came to music as most normal folks would,” Quinn said. “I didn’t grow up playing violin from the age of 3. I wasn’t a huge fan of classical music until college. Neither of my parents was a musician, but they were music aficionados. In my household growing up, I can’t remember a moment not listening to music, from Barbra Streisand to Beethoven. I started singing in choir in first grade, but I didn’t read music until I attended PC.”

As a student at Notre Dame High School in West Haven, Conn., Quinn’s plan was to study communications and become a weather forecaster. Because his family vacationed in Rhode Island, he decided to tour Providence College.

“I knew when I saw it that it was the place for me,” Quinn said. “I vividly remember being moved even by the Dominican cemetery. The priests didn’t just live in the dorms but were there as part of the College’s history. I didn’t visit the music department because I was totally undecided about a major. I just had a great, indescribable feeling about the College, the spiritual and community aspect. I just couldn’t believe how wonderful everybody was there.”

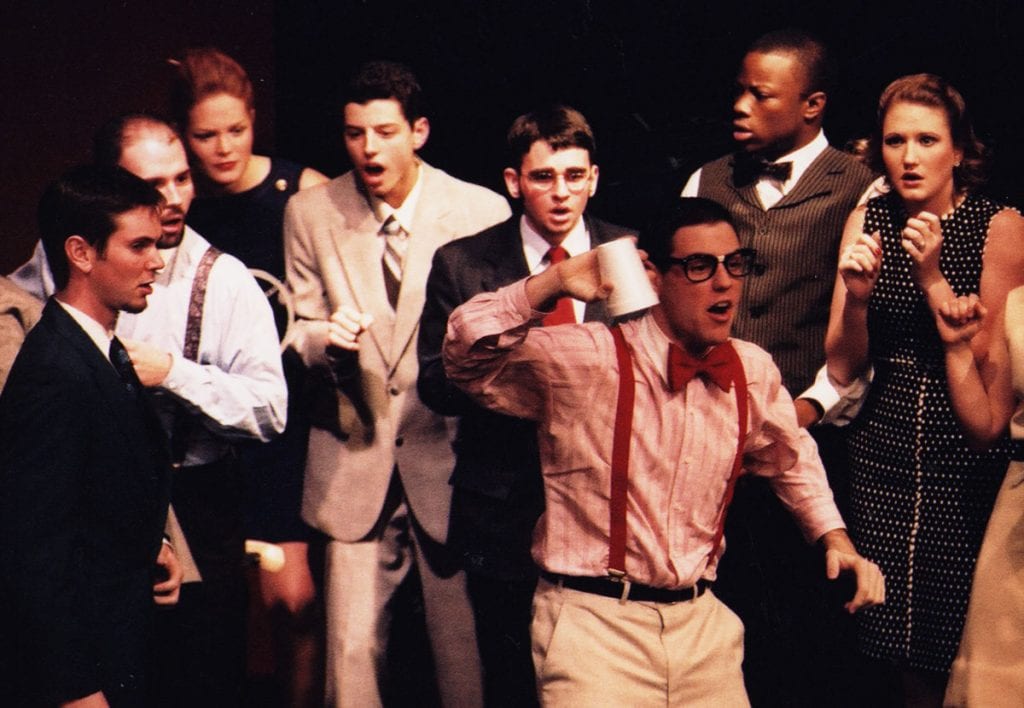

As a first-year student, Quinn sang in the musical How to Succeed in Business Without Really Trying. He caught the attention of Dr. Michele Holt, director of choral activities, and David Harper, associate professor of music, who encouraged him to audition for the College’s premier choir, I Cantori, and to take music classes.

During a choir rehearsal in Guzman Hall chapel, which served as the music room before the Smith Center for the Arts was built, Dr. Holt asked Quinn to conduct the choir.

“She recognized some raw innate talent in me and said, ‘Come up and conduct this piece,’” Quinn said. “It was ‘Prayer of the Children.’ I had no idea what I was doing, but she saw my musicality, and that I could be trained. That started the transition from singing to conducting.

“I didn’t know anything,” Quinn added. “I just had a decent ear. You can train a monkey to do the conducting gestures, but the ear has to be innate. You either have it or you don’t.”

During his senior year, Quinn did an independent study, conducting the choir and orchestra in Handel’s Messiah for Christmas, but his focus remained singing. After graduation, he entered the Manhattan School of Music to study opera and vocal performance in a two-year master’s program.

“It was world-class training with the best of the best, but I missed Providence, that community feeling,” Quinn said. When he finished the degree, he returned to PC for three years to work as a part-time instructor of voice and conductor of the women’s choir.

“I was a very green faculty member,” Quinn said. “I had come full circle. It was a wonderful experience for me. My teachers were now my colleagues. I felt honored and humbled and also, somewhat, ‘What am I doing here?’ In my world, conducting is, in essence, teaching. I was able to hone my profession in an environment that was encouraging. There is nowhere else in the country you could do that as a 25-year-old musician.”

While at PC, Quinn also taught at Portsmouth Abbey, a private high school for boarding and day students in Rhode Island. To gain experience as a conductor, he established the Portsmouth Institute Orchestra, made up of musicians from the Rhode Island Philharmonic and Boston Pops who were available to play in the summer. It was so successful that Quinn returned to Rhode Island to conduct even while studying for a doctorate in Los Angeles.

“It propelled me,” Quinn said. “How do you get experience? ‘I will start my own orchestra.’ I was making mistakes and learning the ropes with world-class musicians.”

Quinn was awarded a full scholarship to study for a doctorate in conducting at USC.

“If I was going to do it all the way and really make it, I had to leave the East Coast,” Quinn said. “I did the degree in four years, as quickly as you can do it, finishing in 2014. The irony is that I came back to teach at USC three years later. It was a parallel experience on the West Coast.”

In Los Angeles, talented artists have the opportunity to sing and play in orchestras on film soundtracks, TV shows, and albums. As a doctoral student, Quinn took advantage of studio work. He sang background for movies and TV, including Glee and two Barry Manilow specials, and on Josh Groban’s Stages album.

In 2013, when the Rolling Stones brought their 50 & Counting Tour to the West Coast, Quinn performed with them as a backup singer. When the Stones needed someone to conduct the choir in “You Can’t Always Get What You Want” onstage at a concert in Buffalo, N.Y., Quinn happily filled in.

“I’m on the stage with Mick, and it’s, ‘Let’s go through this once, then we’ll go through it again, Troy.’ They are fantastic musicians. They can still kill it,” Quinn said. “I got to see a little of the behind-the-scenes. I love just being involved in that world-class level of music-making. I’m just happy I’m in the room. They are the best of the best.”

Quinn accepted a three-year contract in 2015 to be music director and conductor of the Juneau Symphony in Alaska, which performs from October to May. He was able to work from Los Angeles, traveling to Juneau for rehearsals and concerts.

“It’s an unusual schedule, that of the 21st-century, modern conductor,” Quinn said. “You fly in and out of communities. You’re involved in the day-to-day operations. I am involved in Skype and phone meetings. I tell people it’s like working from home, except for performing the concerts.”

In 2017, Quinn became music director of the Owensboro Symphony Orchestra in Kentucky. When his contract ended in Juneau in 2018, he added the Venice Symphony in Florida.

To conduct, you learn by doing, Quinn said.

“They throw you in the fire and you do it,” Quinn said. “I never had a famous conducting teacher or mentor. I studied with world-class people but never a mentor one-on-one after PC. I always say I’m a blue-collar conductor. I learned on site by getting my hands dirty and getting in the trenches.”

As music director, Quinn hires musicians and plans concerts. He considers music selection to be key, to sell tickets and to please audiences and musicians.

“The music director decides what shows to do,” Quinn said. “That’s the beauty of it. It’s lovely. I pick the repertoire and the soloists. It’s a daunting task and the most important part. Any success I’ve had is due to programming. I try to appeal to young and old, to reach the younger generations. I’ve done progressive, hybrid concerts, with Beethoven and a film score in the same concert. Music is either good or bad, in my opinion. My background is all these different genres. I love all kinds of music, music for everybody that reaches all folks.”

There are three parts to music selection: Will the audience like it? Will the musicians like it and feel challenged by it? And can Quinn live with it for months?

“My barometer is: Would I have liked this before I knew anything about how great Mozart is? Is this going to appeal to your average American citizen? Is the music good?” Quinn said.

“How do we reach people who won’t sit down for three hours? We do it in new and relative ways. The music speaks for itself. To get people to listen to it, you have to think outside the box. Does this music move me? I have the good fortune of still being fairly young. It helps to connect with current trends in the industry. And some things are timeless. That’s why Beethoven’s been around for 300 years.”

Tastes vary geographically, Quinn said.

“I can’t do a new music piece in one part of the United States that I could in another part,” Quinn said. “In New York, you can do a lot of avant-garde, ear-bending stuff that would not fly in Florida or Kentucky. Country won’t work in Juneau. It’s absolutely an aspect you have to consider when programming.”

At USC, Quinn teaches the art of conducting.

“Conducting is art,” Quinn said. “The gesture keeps the time. But with these great orchestras, they don’t need me to just sit there and beat time. They need me to interpret music as the composer intended and to be the conduit between the composer and the orchestra. What did the composer intend? Does the music get louder or softer? I am a communicator of music — without making a sound, ironically.”

Quinn sees his role as that of a diplomatic middleman.

“You have a duty to be true to the composer’s intention and convince 80 people to go along with that and play their best,” Quinn said. “I am still usually one of the youngest people in the room when I step on the podium. Grammy-winning, Oscar-winning people are thinking, ‘What is this whippersnapper going to tell me?’ If I make the work about the music, everybody respects that, and there’s no ego in the way at all.”

Quinn’s brother, Shane Quinn ’07, who majored in theatre at PC, now works in arts administration at Yale School of Drama. Quinn and his fiancé, Sheeba Alam, a sales manager and mezzo-soprano from Chicago, will marry in May.

“It’s hard to describe my affinity for Providence College,” Quinn said. “It’s a place where I developed musically, emotionally, and spiritually. I’m greatly indebted to it, and I love it very dearly. I made lifelong friends there. I’ve returned to do master classes. I’ll do anything I can to be involved. I always say my first million will go to the school, if I make it. My dream is that, in some capacity, I’m not totally finished with PC. Maybe I’ll end up back in Rhode Island someday.”