Providence Proud: 50 Years after Twin NIT Titles, Player Friendships and the Friar Faithful Endure

By Vicki-Ann Downing

The early 1960s was an exciting time in America. A young president was in the White House, civil rights activists were marching on Washington, and at Providence College, basketball players were stunning sports fans by winning national championships that launched a storied tradition and ignited a statewide fan base.

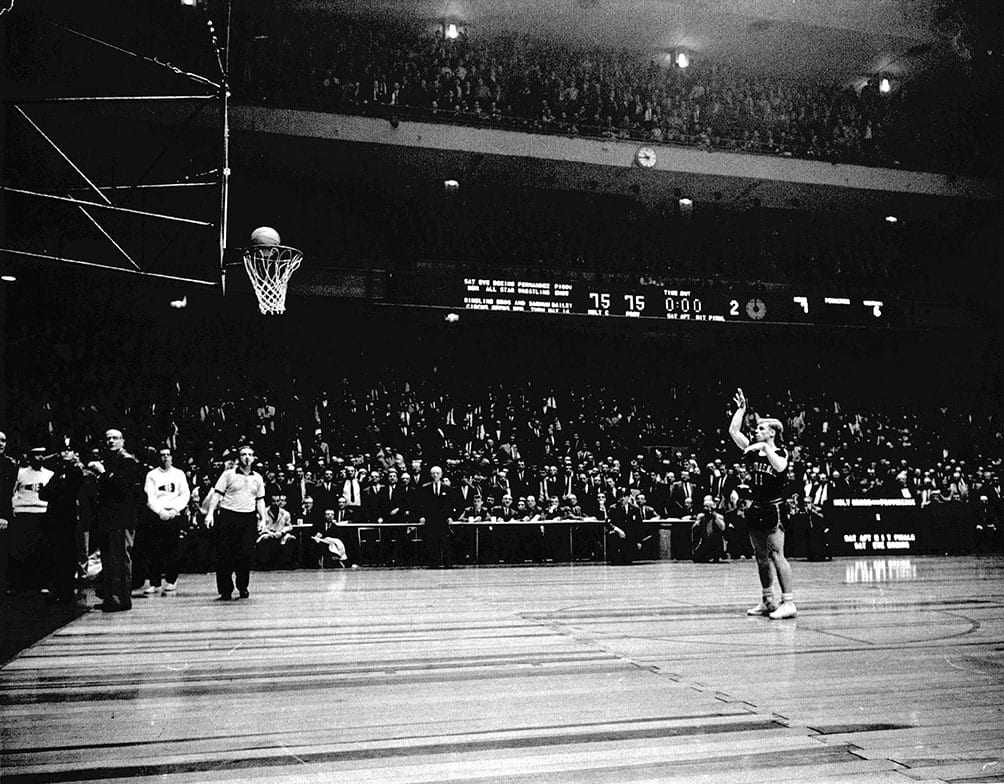

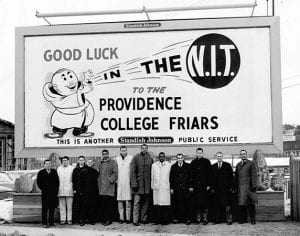

Raymond L. Flynn ’63 & ’84Hon., who later served as Boston mayor and Vatican ambassador, starred on the PC teams that won the National Invitational Tournament (NIT) in 1961 and 1963. At the time, the NIT was the popular college tournament because it was played on a national stage — the old Madison Square Garden in New York City.

Looking back across five decades, Flynn, who grew up in South Boston, Mass., is struck by how young men from different races, neighborhoods, and backgrounds came together so successfully to win — and then went on to impressionable careers in basketball, politics, law, and medicine, with several establishing charitable foundations to continue their good works.

“Our teams demonstrated a remarkable sense of teamwork and racial unity wherever we played, from Cincinnati to Philadelphia to San Francisco to Boston,” said Flynn. “It was apparent to all watching that we were a team and played for one another and for our proud school. That’s why a small, Catholic college in the smallest state could bring black and white spectators to their feet to cheer for a college they had hardly heard of.”

The two NIT championships “changed everything” for Providence basketball, said Bill Reynolds, a sportswriter for The Providence Journal who was a high school student then. After both championships, fans lined Route 6 from the Connecticut border in Foster, R.I., all the way to Providence, where thousands of joyous people awaited the team.

The success wasn’t just luck, said Rev. Robert A. Morris, O.P. ’46 & ’82Hon., a retired PC English professor and former College executive vice president, who remains a cherished friend of players from the era.

Father Morris credits the foresight of then-College President Rev. Robert J. Slavin, O.P. ’28, who believed that “five guys on a basketball court” could put PC on the map. In 1955, under Father Slavin’s leadership, PC built a home for basketball, the 3,000-seat Alumni Hall, and hired a new, young coach, Joe Mullaney ’65Hon. & ’98Hon.

“They had a great coach who had a vision. That was the foundation,” said Reynolds. “The school was trying to be good. They had a new gym on campus, impressive for that era. They were able to get a couple of guys who fell through the cracks recruiting-wise. That’s how they built it all.”

Discipline and education

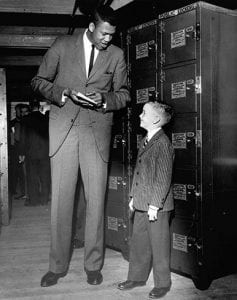

PC’s first superstars were John F. Egan ’61 and Leonard R. “Lenny” Wilkens ’60 & ’91Hon., who formed what some called the best backcourt in college basketball. Egan, from Hartford, Conn., had been an All-America high school player. Wilkens, from Brooklyn, N.Y., was a surprise success, invited to join the team after Mullaney’s father saw him playing in a Brooklyn gym.

Both went on to play and coach in the NBA. Egan retired as coach of the Houston Rockets. Wilkens is the only three-time inductee to the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame — as player, NBA coach, and Olympics coach.

They remain friends. In August, Egan traveled from Houston, where he is active in charitable causes, to Seattle for a Celebrity Weekend to benefit the Lenny Wilkens Foundation, which funds education and health care for needy children.

Wilkens recalls “a great atmosphere on campus and a sense of pride about Providence. We all shared in it. We wanted people to know of us. It was important. We took pride in that we went to Providence (College), when we went to a movie or downtown.”

“Providence was such a great school, with discipline and education, and teaching guys how to be men,” said Egan. “Our team had talent, but we weren’t over-talented. We had to struggle through. We didn’t blow people out. We worked as a cohesive unit, and no one really had a huge ego where they wanted to be the star. I told Lenny, ‘We never had any problems. We really didn’t know what we were doing, did we? We just played.’”

Timothy C. Moynahan ’61, a forward who became a lawyer in Waterbury, Conn., believes good fortune was a factor, too.

“The really lucky part is this: you weren’t given a character test to talk about your unselfishness, your willingness to subordinate yourself to the good of the team, your discipline, and your good habits,” said Moynahan. “The 12 guys we had on the team were extraordinary — good characters leading clean lives, no self-centered people. That’s luck. You can’t be good enough to pick 12 people like that.”

Race “just wasn’t an issue for us. If anything, we could be criticized for not being aware of the race issue,” said Moynahan, who was a law student in D.C. during the March on Washington. “At Providence College, it just had not arrived. We were on the threshold of everything that was going to happen.”

John Thompson, Jr. ’64 arrived at PC as a nationally recruited basketball player from Washington, D.C. In 1984, as head coach at Georgetown University, he made NCAA history as the first African-American coach to win a national championship. Social issues weren’t discussed by the PC team, Thompson said. The focus was winning.

“The team never stood for any social movement. That doesn’t mean there was something bad or mean about it,” said Thompson.

“We played basketball games, and we won those games. There were good people in Providence who made me feel comfortable being away from home for the first time and going to school in New England. It was a pleasant experience for me. Those Dominican fathers were good, down-to-earth people.”

Embraced by the city

PC was an all-male school with about 2,400 students, most of them commuters. Dominican priests not only taught classes but lived in residence halls, enforcing study times and lights out at 11. Freshmen wore beanies for their first six weeks of school. Everyone wore jackets and ties to class. The coach’s wife sometimes cooked dinner for the players.

Providence supported the team, and not just by watching games. In particular, Moynahan and Thompson remember the kindness of Austin and Genevieve Grady, who ran a small diner across from the Newport Creamery on Smith Street.

“They were just as sweet to me as they could be,” said Thompson. “I always felt at home when I sat down and talked to the Gradys.”

Moynahan and his roommate, Egan, stopped by Saturday afternoons for sandwiches and orange juice. Whenever they paid the $1 charge, Austin Grady handed them two half-dollars in change.

“We were embraced by members of the community, people who loved Providence College and started following the team,” said Moynahan. “I think they recognized the fact we were clean-cut kids, and they virtually took us into their families, their homes, they fed us.”

Looking back, the players realize how different the times were.

Flynn hitchhiked from Boston to Providence for his PC tryout. Classmates remember him “at Mass, at class, or in the gym.” Thomas M. Murphy ’63 recalls returning to campus late on Saturday nights and hearing the “boom, boom, boom” of a basketball in Alumni Hall — the sound of Flynn practicing his shooting.

Richard T. Leonard ’62, who described himself as a “farm boy from East Hartford, Conn.,” wasn’t recruited to play basketball but made the team after a try-out.

“For me especially, as a walk-on player, to be able to play in Madison Square Garden in a championship game was great,” said Leonard, of Narragansett, R.I., who was senior vice president for Pratt & Whitney aircraft for more than 30 years.

Richard E. Holzheimer, M.D. ’61, a retired physician in Euclid, Ohio, was a pre-med student who came to PC on a basketball scholarship because his coach knew Mullaney. Every afternoon he went straight from the lab to the gym for practice — a schedule that would be daunting for a pre-med student playing Division I basketball today.

“It was a perfect time,” said Holzheimer. “We never dreamt it would be what it was. It was just unbelievably exciting to the student body and to us.”

George R. Zalucki ’63, a high school rival of Egan’s from Hartford, Conn., served in the Marine Corps before coming to PC. In the 1961 NIT Championship contest against St. Louis University, he had his best game, 17 points and 10 rebounds. He became the father of nine, taught and coached at the college level, and worked as a chief of probation before becoming an international personal development trainer, writer, and lecturer. He lives in Tennessee and Florida.

“Without that ’61 team, Providence College never would have had the start to become what it was for so many years,” said Zalucki. “There never would have been a Marvin Barnes or a Jimmy Walker. The genesis of Providence College’s success was that team.”

Friendships, memories endure

Few games were televised, so students and fans across Rhode Island tuned in to their transistor radios to listen to broadcasts by Chris Clark. During the NIT, campus emptied.

“It seemed like we were always playing in New York City right before St. Patrick’s Day,” said Francis E. Macchi ’61 of East Hartford, Conn., who played basketball as a freshman and followed the team every year after that. “We would stay at the homes of Long Island kids, or end up getting a room at a hotel for about $12, and six of us would sleep in the room.”

Owen V. Cummings ’61 of Lusby, Md., remembers the thrill of seeing “Providence” on the Madison Square Garden marquee. After a late night celebrating the overtime win in 1961, PC students got word that another student had a hotel room in the city.

“Getting off the elevator, we didn’t know if the room was to our right or to our left,” said Cummings. “Without being asked, the security guard politely told us that ‘the room is down to the right.’ I guess he remembered that he was a kid once, too. Embarrassed, we put our heads down and found the room. … Nineteen of us spent the night there, and all floor space was taken.”

The friendships endure, too. The players email one another from homes around the country. Some came to Providence to celebrate Father Morris’ 90th birthday. In August, Leonard, Holzheimer, Zalucki, Macchi, and Cummings reunited in Saratoga Springs, N.Y.

Their brilliant coach, Mullaney, died in 2000. His assistant, Dave Gavitt ’89Hon., founder of the BIG EAST Conference, died in 2011. Many of the great players are gone, too. Jim Hadnot ’62, the 6-foot 10-inch center drafted by the Boston Celtics, died in 1998. Vinnie Ernst ’63, the 5-foot 8-inch point guard from Jersey City, N.J., died in 1996. And Jimmy Stone ’64, who might have had a professional career if not for a bad knee, died in 2006.

Flynn recalls an incident involving Ernst and Stone during the 1962-63 season. The Friars flew into Cincinnati-Northern Kentucky International Airport for games against Dayton and Xavier. Arriving late at their Cincinnati hotel, the players headed into a coffee shop in the lobby. Somehow, it was quietly suggested to Stone, who was black, that he instead try a diner down the street.

“We were very hurt, Vinnie Ernst and myself, and we walked two blocks with Stoney to an all-night diner in the cold city of Cincinnati,” said Flynn. “It was probably the proudest thing we did at Providence College, and that includes winning two NIT championships.”

Comments on “Providence Proud: 50 Years after Twin NIT Titles, Player Friendships and the Friar Faithful Endure”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

I have long believed that this story and the historic era would make a great movie. The Civil Rights Movement, the fight for equality in America, Dr. Martin Luther King, President John F. Kennedy and yes, a small unheard of Catholic college in the smallest state in the nation became a part of it. The Friars showed the country, that in sports and in life, it’s all about teamwork and working together.

Vicki-Ann, you certainly captured that.

Ray Flynn

obviously at the very least a book should be written..this is a story that has an impact on a Colege, a city, a State and in it’s evolution the nation of basketball.

I was in Jr. High School in Newport in the early 1960’s and remember well listening to Chris Clark on the radio (with Jerry Capstein reporting the player’s stats) with a pad and pencil in my hand keeping score. I don’t believe I ever missed a game. It was a very exciting time for us in Little Rhody with the Friars traveling the country and winning important tournaments. It gave us a great deal of pride. We all imagined ourselves to be Johnny Egan or Vinnie Ernst or Ray Flynn when playing basketball outdoors in freezing temperatures at the Richmond Lot in the 5th Ward sinking the game-winning jump shot from 25-feet…..those were the days. Thanks to the Friars for all those great memories.