Remembering William P. Haas, Ph.D. ’48, former college president

Editor’s Note: William Paul Haas, Ph.D. ’48, the eighth president of Providence College, died May 9, 2023, in Glastonbury, Connecticut. This reflection is an excerpt from Providence College in the 1960s: An Era of Change, written by Mario DiNunzio, Ph.D. ’57, ’22Hon., professor emeritus of history.

By Mario DiNunzio, Ph.D. ’57, ’22Hon.

A turning point in the history of Providence College came in 1965 upon the retirement of the venerable and highly respected president, Rev. Vincent Dore, O.P. ’23. The Province of St. Joseph had elected a new provincial, Rev. Louis Every, O.P. Every was not an academic; he had recently returned from mission work in Pakistan. But he was very much interested in the college, and in line with what was happening in Rome at the time of the Second Vatican Council, he sought a kind of aggiornamento, or modernizing, of the college. Every, as was the custom then, appointed a successor to Dore. He chose a 36-year-old Dominican who had taught philosophy at the college a few years earlier but was doing post-doctoral study at Notre Dame. He was Rev. William Paul Haas, O.P. ’48, who brought a new administration and new life to Providence College.

Among his first appointments, Father Haas named Paul van K. Thomson to fill a new office, vice president for academic administration. Thomson was an Episcopal priest who converted to Catholicism after he joined the PC faculty in 1948. In 1956, when he decided to accept a position at Newton College of the Sacred Heart, near Boston, College President Rev. Robert J. Slavin, O.P. ’28, asked him to name his price for remaining at PC. The price was permission to establish a humanities honors program. Thomson stayed and the first honors class was recruited from among the entering freshmen in the fall of 1957.

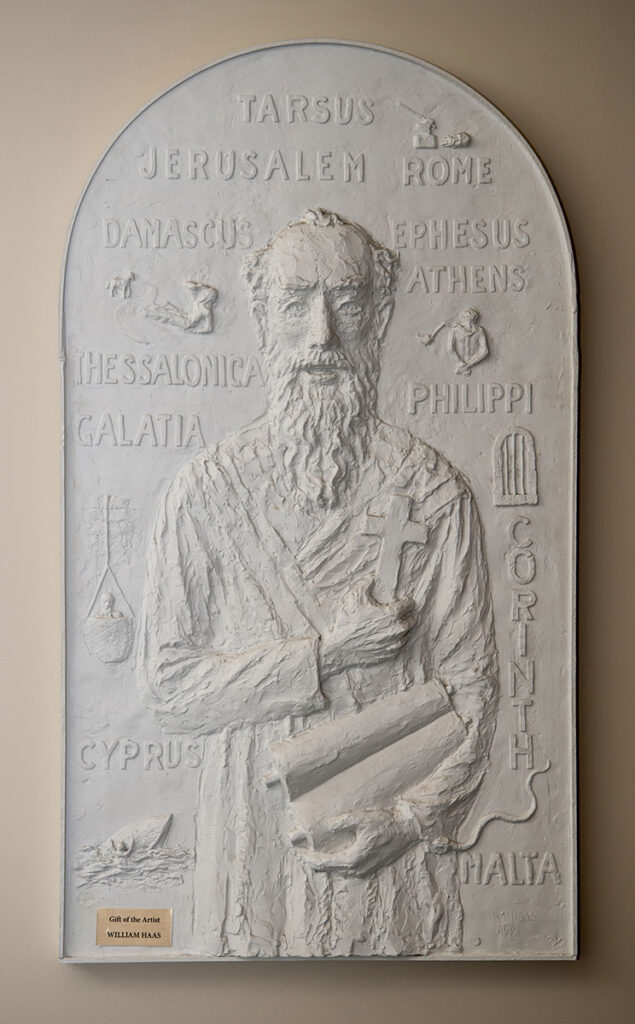

William Haas was a talented leader and an excellent and persuasive speaker. His command of language, timing, and nuance inevitably captivated his audiences from the lectern as well as the pulpit. When a last-minute cancellation left the college without a commencement speaker in 1966, Father Haas delivered what many faculty agreed was the best commencement address they had ever heard. He was also a gifted painter and sculptor. His plaque depicting the life of Saint Paul hangs in the Ruane Center for the Humanities. He was also possessed of sensitive political skills. In some ways Haas was Lincolnesque in dealing with difficult situations.

This was an era of frequent student protests at American universities, including Providence College. One springtime students decided to march on the president’s office with non-negotiable demands. (“Non-negotiable” inevitably accompanied student demands in the Sixties.) As students jammed the presidential complex, Haas pointed out there were too many for all to hear. Why not go to the lower-level auditorium so that all could join in. The students agreed; the president won the first round. Father Haas climbed to the stage, looked at the demands and said, “Is this all?” He could think of a lot more that was wrong. He proceeded to detail his hopes for progress at Providence College. When he finished, the non-negotiators gave him a standing ovation and left the hall. It was some time before they realized they’d been had, and it was too embarrassing to renew the protest. Besides, exams were approaching, and the summer break was near.

Father Haas always spoke with an awareness of his audience and an understanding of time and place. He accepted an invitation to deliver the baccalaureate address to the Brown University graduating class of 1967. At the First Baptist Church he wore his Dominican habit instead of traditional academic attire to dramatize the occasion of a Catholic priest of a medieval order speaking from the pulpit of a Reformation church. There he reflected on the ecumenical hopes of the Second Vatican Council. Introducing himself as one dressed in a friar’s garb, stained with blood of fellow Christians and Jews at the hands of the Inquisition, he spoke in the spirit of a long-delayed reconciliation after centuries of vicious hostilities. He made it a deeply moving event.

Among the first tasks of the new administration was to organize a centralized faculty structure. In the preceding era, with few lay faculty, department chairs hired new faculty and there was no central personnel file. Thomson called on all faculty to submit credentials and discovered that in a couple of cases degree claims were questionable. What followed was establishment of a Committee on Rank and Tenure, a formal process for granting tenure and promotions, and standards for new hires as the lay faculty grew.

The faculty was generally welcoming and cooperative with the Haas-Thomson administration but showed independence. In 1965 a college chapter of the American Association of University Professors was formed, though the administration had counseled delay. On the evening of November 9, 1965, the lights went out. It was the great blackout of the northeastern United States. With classes abruptly ended, a small group of faculty retreated to the cafeteria, which had emergency lighting. With coffee and a yen to influence the direction of the new administration, they hatched a plan to form a chapter of the AAUP. At that time the AAUP had great influence on the standards governing faculty in American colleges and universities. Despite the president’s reservations, the chapter was established.

Among the first actions was a call to create a Faculty Senate, to which the president responded positively. The Senate was instrumental in reshaping college tenure and promotion standards, providing for the election of department chairs by faculty, gaining faculty representation on the college budget committee, and endorsing the establishment of a psychology department and programs in drama and film, art, and music.

The Senate also took the first failed step toward co-education in 1968. A resolution to study the possibility of admitting women failed to pass. Many all-male Catholic colleges had begun to admit women in the face of declining enrollment. The administration was reluctant, insisting that the college should continue as it was, preserving “a healthy all-male atmosphere.”

The next year saw a continuing drop in enrollment and a steep budget deficit. Prudence dictated reconsideration, and in the 1969-1970 session, the Senate adopted a resolution to admit women, and the administration approved. Women were enrolled in the freshman class in 1971 and quickly displayed their scholarly expertise.

Among the greatest achievements of the Haas administration was the revision of the college curriculum. The curriculum demanded so many required courses that there was little opportunity for elective choices, and in most majors six courses per semester were needed to meet all requirements. These included 18 credits in theology, 18 in philosophy, and more required courses in history, English, and a foreign language. When Father Dore was dean of students in the 1950s, the “big board” in his office contained a card slot for every course offered. There were so many requirements and so many multiple sections that Father Dore solved any problems with a quick reference to the board. Sometimes the solution was accompanied by the phrase, “For your elective you will take …”

The study committee, which included students and faculty, was led by Thomson and English Professor Rene Fortin, an award-winning teacher and respected scholar who served as director of the college honors program. Also serving on the committee was Rodney Delasanta, an equally gifted teacher and prolific scholar, and Rev. Thomas R. Peterson, O.P. ’51, dean of students. They interviewed members of every department, tested ideas, and solicited suggestions. The result was a proposal for a completely new core curriculum, with a sharp reduction in requirements and much innovation.

The centerpiece was a four-semester, 20-credit course, the Development of Western Civilization. This was an adaptation of a kind of “great books” course in the college honors program. A key difference was that books were to be studied in historical and cultural context. The course combined studies in history, literature, philosophy, religion, art, and music. Classes were to meet five hours per week and be team-taught by members of the relevant departments. The proposal became the focus of intense debate. The education and business departments, with heavy requirements for majors, feared the new core would cut into their credits. Many Dominicans, especially but not exclusively in philosophy and theology, were firmly opposed because it would reduce the number of credits in those departments to a total of 12 and stray from the Thomistic character of their courses. The history department divided evenly, pro and con; and the English department strongly favored the proposal.

The 1969-1970 session of the Faculty Senate passed the new core curriculum by an overwhelming vote. The legislation was signed and strongly applauded by Father Haas. The architects were inspired by Cardinal John Henry Newman’s The Idea of a University. They understood that, beyond specialized knowledge, an understanding of the interplay of history and culture was essential to the development of the mind and serious pursuit of excellence in one’s education. The Development of Western Civilization Program became the centerpiece of a Providence College education.

The period from 1968-1971 was a tumultuous time for the college and the country. The college was confronted with repeated episodes of protest against the Vietnam war. There was some feeling on campus that the government’s military policy should not be questioned in war time, and the issue was much debated. By a vote of the Faculty Senate and with the approval of the president, the college joined the nationwide Moratorium in October 1969, when classes were suspended for “teach-ins” and antiwar speeches on the lawn in front of Aquinas Hall.

The climax of anti-Vietnam protests came in response to the shooting of student protestors at Kent State University in May 1970. During a special evening session, with the president in attendance signing bills as they were passed, the Senate voted to join the national academic strike protesting the war. There was only one dissenting vote. Several tense days followed, and given the disruption, the administration announced that final exams would be optional.

In 1971, after six years of intense and transformative activity, Father Haas resigned the presidency and was succeeded by Father Peterson. Father Haas remained at the college, joining a team to teach in the first year of the Civ program. He left during the 1972-1973 academic year for post-doctoral studies at Boston University. During that year he appealed to the Vatican for laicization, was approved, and subsequently married Pauline Burke, who had been his secretary. Rev. Charles Duffy, O.P., his seminary classmate, officiated. Moving to Massachusetts, he became president of North Adams State College. He later returned to Rhode Island to live in Newport and teach philosophy at Bryant University and Salve Regina University.

Thomson remained as vice president and continued to lead and inspire academic progress. In 1980, when the Vatican opened a path to ordination for Episcopal priests who had converted to Catholicism, Thomson was deemed qualified, and, still the vice president, became a Catholic priest with a wife and seven children. A moment of arresting drama occurred when Father Thomson was assisting at St. Mary’s Church in Newport. Father Thomson presided at the Eucharist, Pauline Haas was the Eucharistic minister, and she offered communion to layman Bill Haas. Real life is often stranger than fiction.

The Haas-Thomson years were important for Providence College. The objective was to build a reputation for excellence among American colleges that would draw honor and attract students. The effort was dedicated to fulfilling the traditional mission of the Order and the college. With a healthy working relationship between administration and faculty, the project succeeded. Faculty volunteered much time and energy to the work of reform. Devoted to their teaching and scholarship, they also displayed a deep sense of commitment to the college as an institution. That spirit was captured one day by Rene Fortin when he described the college as “this sacred place.” For years, Providence College ran on the steam generated during that period.

Mario DiNunzio, Ph.D. ’57, ’22Hon., professor emeritus of history, began teaching at Providence College in 1960 and was awarded an honorary doctor of humanities degree at commencement in 2022. His reflection, Providence College in the 1960s: An Era of Change, is available at Phillips Memorial Library and at digitalcommons.providence.edu.