Sand in his shoes: A visit with Bill Burke ’84, historian for Cape Cod National Seashore

By Michael Hagan ’15, ’19G

It’s a long way from the Bourne or Sagamore bridge to Cape Cod National Seashore, where 40 miles of federally protected beaches, woods, and ponds, covering 43,600 acres, run from Chatham in the south to Provincetown in the north. Driving along the two-lane highway to the Outer Cape, visitors can feel they’re headed nowhere.

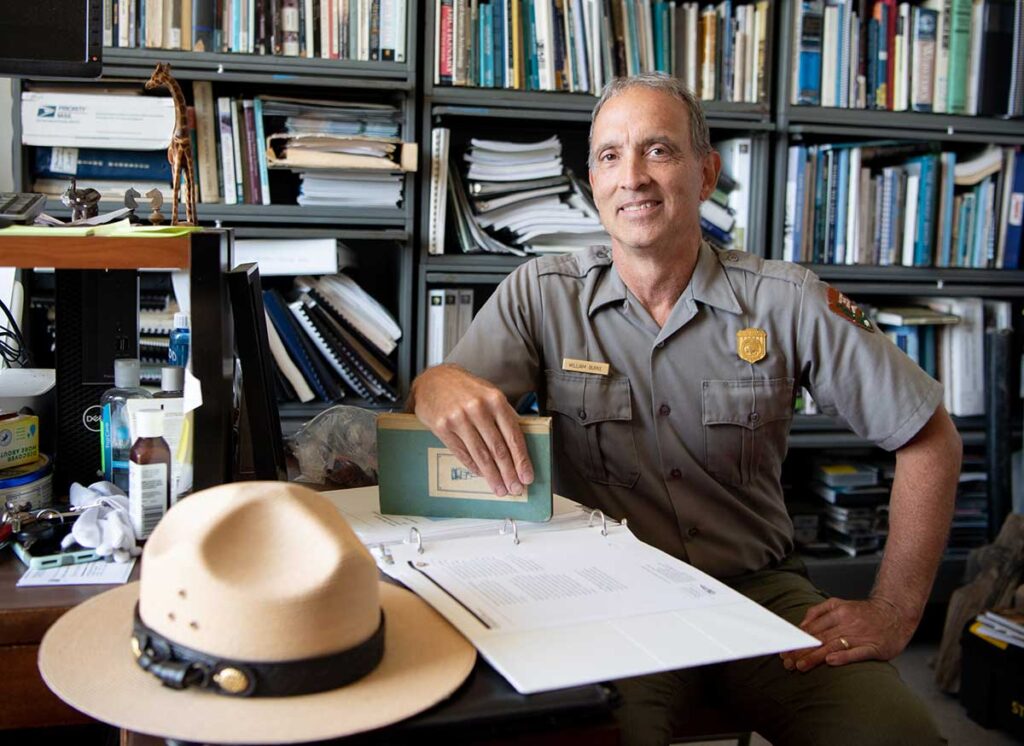

In a sense, they are. Cape Cod is “a grand place to be alone and undisturbed,” playwright Eugene O’Neill wrote in 1919. In the 19th century, Henry David Thoreau described it as “a sort of neutral ground, a most advantageous point from which to contemplate this world.” This quote greets visitors to the Salt Pond Visitor Center in Eastham, where guests can see artifacts dating back centuries. If they’re lucky enough, they will encounter William “Bill” Burke ’84, cultural resources program manager for Cape Cod National Seashore — in other words, the park’s historian.

Burke has worked for the National Park Service since college and at the national seashore since 1988. He oversees the process by which historical artifacts and data become historical narrative ready for consumption by visitors eager to learn the natural and human history of Cape Cod. Thanks to his work, loose flotsam tells the stories of shipwrecks, scrimshaw (carved whale bone) the stories of the whalers who chiseled it, and dune shacks the stories of families who waited anxiously for sailors to return from sea over the Cape’s long maritime history.

Burke is about average height, but his distinctive park ranger Stetson hat adds several inches to his stature. His neutral-toned uniform conveys authority — not in terms of giving orders (though he will not hesitate to enforce park protocol), but rather in commanding knowledge. His demeanor is inviting, and he smiles naturally when he speaks.

He is a natural storyteller who has been interviewed dozens of times for documentary films and published articles about Cape Cod’s history. During the summer, he was interviewed for a History Channel program about the Whydah — the only documented pirate shipwreck in the world, which lies within the national seashore’s waters.

In a room under the visitor center, Burke handles artifacts and processes primary data, adding to and interpreting Cape Cod’s historical record each day. In a backroom, primary source documents, including lighthouse keeper’s logs, whaling journals, and maps, fill boxes on shelves that wrap around the walls floor-to-ceiling. This windowless, subterranean space is nothing like the sunny seaside climate outdoors, but the cool, dark, and dry environment keeps delicate materials safe from the elements.

Preservation is a struggle against the environment. The coastal weather exacts a toll on historic buildings and other sites. And if the tide brings items ashore or unearths artifacts buried in the sand, preservationists have only until the tide returns to safely relocate them before they are washed out to sea. Recently, visitors to the beach recovered a British naval pistol from 1759 that the park now preserves.

Burke has worked at Cape Cod National Seashore for more than half its history. The national park was established in 1961, the year before he was born, under President John F. Kennedy, whose family keeps its well-known compound in Hyannis to this day.

A protected seashore on Cape Cod was a controversial idea. Residents and merchants feared losing their property to eminent domain. The park was intended to stymie large scale development, which worried investors who envisioned booming beach towns like Atlantic City, N.J., and Ocean City, Md. The Cape Cod National Seashore began as an experiment — a gamble many residents were reluctant to take. Standing atop an ocean bluff overlooking the sea 61 years later, one can hardly imagine doubting the project. Today, more than 4 million people visit Cape Cod each year, often battling summer traffic that is the stuff of legend, to reach this beautiful nowhere.

Much has changed over Burke’s decades here. The scope of his historical project has grown substantially — by about 10,000 years. This is due to increased focus on Native American history. Cape Cod was home to indigenous Americans for millennia before the arrival of European settlers in the early 17th century. The National Park Service has only begun to prioritize native voices and experiences in recent decades. Today, Cape Cod National Seashore partners with two federally recognized native tribes — the Mashpee Wampanoag and Wampanoag Tribe of Gay Head (Aquinnah) — on all ground disturbing activity, in curation and exhibition, and in research.

Cape Cod National Seashore is changing physically as rising seas threaten a land mass that sits only an average of 20 feet above sea level.

“Climate change is the biggest threat to the integrity of the national seashore. There are parts of the beach here that erode 20 feet each year or more. We probably lose about five acres of upland each year,” Burke said.

Even as its seashore erodes, Cape Cod has never been a more popular destination — despite a noteworthy increase in shark sightings and attacks in recent years. In 1972, 11 years after President Kennedy signed the national seashore into existence, President Richard Nixon signed the Marine Mammal Protection Act into law. The number of gray and harbor seals in the waters off Cape Cod increased dramatically in the decades following, and with them, their most feared predator — the great white shark.

Conservationists hail the return of great whites as a sign of environmental healing. Beachgoers are reminded by shark warning flags on beaches, and by each sighting, that when they wade into the ocean, they are visitors in the habitat of other creatures — some more fearsome than others. They visit nonetheless.

“It’s a nationwide phenomenon that people are more into the outdoors now. Cape Cod became even more a place of sanctuary and refuge because of the pandemic,” Burke said.

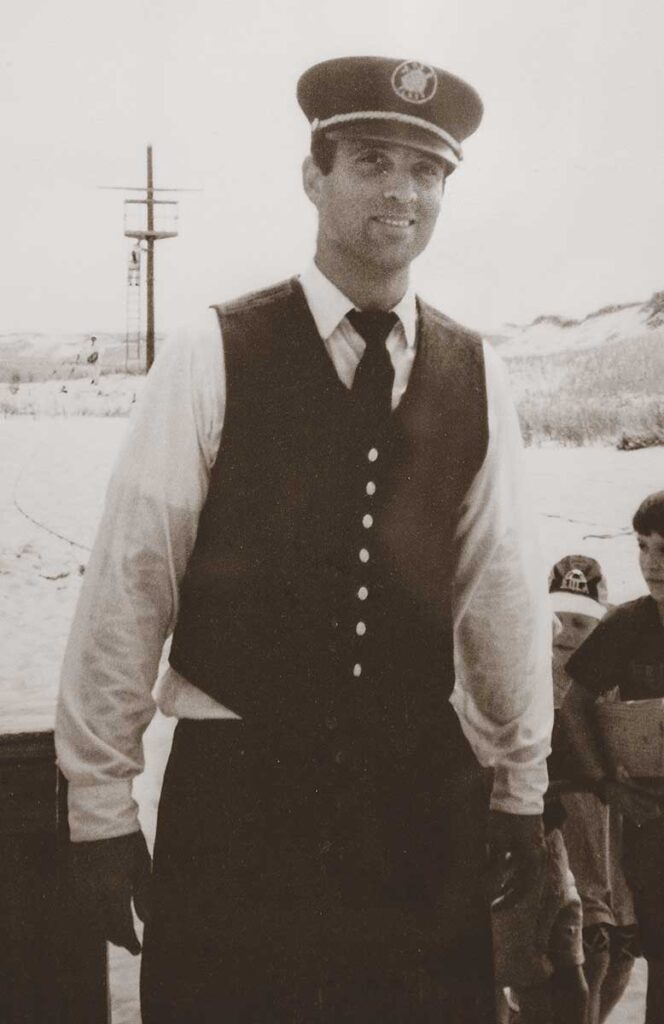

Burke was hired as a supervisory ranger at Cape Cod after completing a master’s degree in colonial history and archaeology at The College of William and Mary. In the five years preceding, he lived and worked for the National Park Service in 13 different places — including two summers at the national seashore.

“Because of my childhood memories, this was my dream park,” Burke said. “Now, I have sand in my shoes.”

Realizing his expression is lost on the uninitiated, Burke explained, “When people move to Cape Cod, they get sand in their shoes. They catch the bug and want to remain by the ocean. I’ll go inland to the mountains, and they’re beautiful, but I always miss the ocean after about a week.”

Burke’s father nurtured a love of history and the seashore in his children. A factory worker, he took his family to Yarmouth on Cape Cod each summer when the plant shut down over the 4th of July holiday. The family also regularly visited historical sites, including the Boston Freedom Trail, John Adams National Historical Park, and battlefields from the American Revolution and Civil War.

“It all comes down to my dad. History was part of our relationship,” Burke said.

Burke’s first job with the National Park Service was a summer position at Saratoga National Historical Park after his sophomore year at Providence College. In 1982, he packed his father’s car and departed from home in Holyoke, Mass., his accommodations uncertain. He stayed at Skidmore College for about two weeks before moving from couch to couch in several homes.

“It was only in hindsight that I realized how generous and trusting my father was in letting me borrow his car for the summer,” Burke said. “He really made that job possible.”

In Saratoga, Burke spent most of his time as a reenactor wearing sweat-soaked 18th century military uniforms in the summer heat.

“The public loves it, but you’re drenched by the end of the day,” Burke said. “Still, I’d take those problems over some of the headaches classroom teachers face.”

Reluctance to become a teacher nearly derailed Burke’s study of history. An Eagle Scout, he loved the outdoors and felt the classroom would be confining. Intent on transferring, he was admitted to forestry schools. But forestry would mean giving up history, and he ultimately declined those opportunities.

“History was my first passion. I decided to stick with it but was determined to find work outside of the classroom engaging the public with history where it happened,” Burke said.

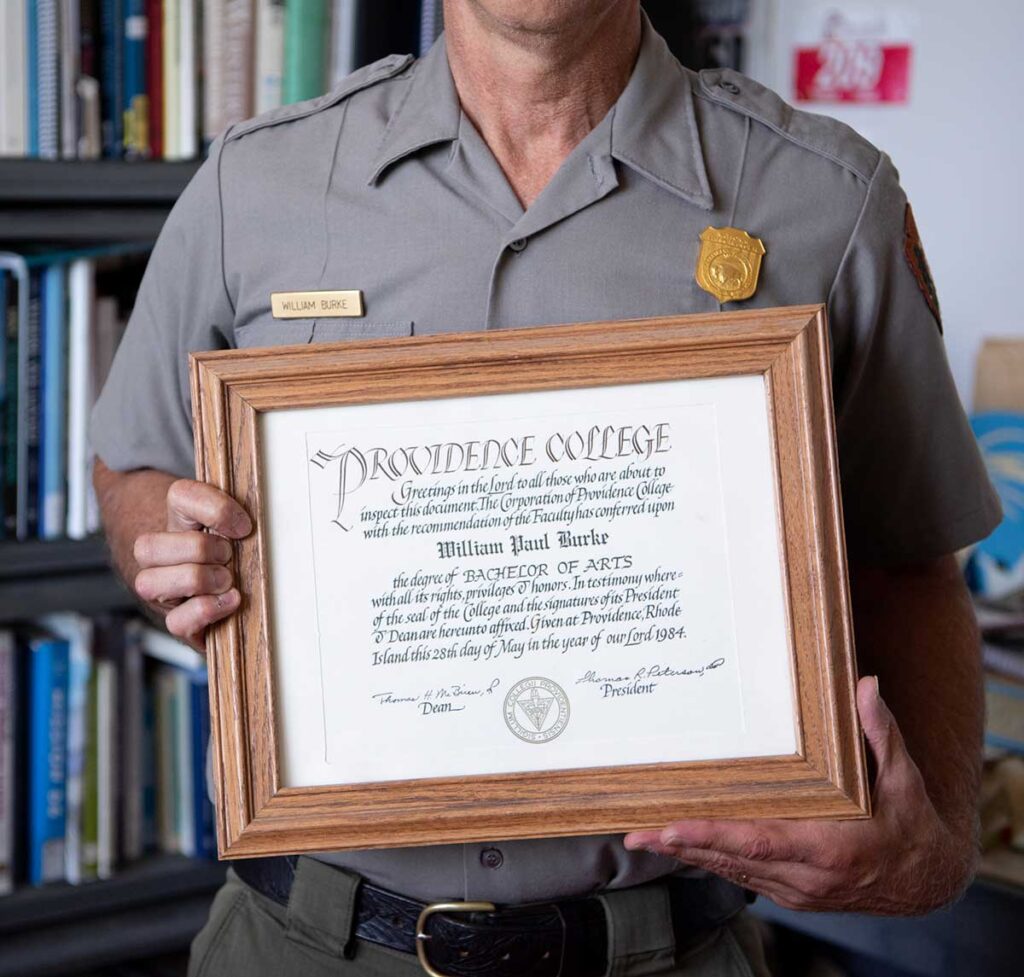

Staying the course at PC, Burke graduated summa cum laude and was awarded the Father Reilly History Award for academic excellence. He recalls learning from iconic faculty, including Richard Grace, Ph.D. ’62, ’17Hon. and the late Donna McCaffrey ’73G, ’83Ph.D., ’87G. He studied for a semester at the University of Fribourg in Switzerland, and he tutored students in the Development of Western Civilization Program.

After graduating, Burke worked at a number of historical sites, including Independence Hall in Philadelphia and Morristown National Historical Park in New Jersey, where George Washington and the Continental Army camped for the winter of 1779-80. In Morristown, he met his wife, Stasia, who was interning there. They married in 1988.

Burke counts himself blessed to live and work within a natural and historical treasure. He and Stasia raised their three daughters on Cape Cod. The family enjoys the small-town atmosphere and natural beauty of their home in Harwich. One might say the whole family has sand in their shoes.

The National Park Service has become a family business for the Burkes. Two of Bill and Stasia’s daughters work at national parks in seasonal positions. The third recently began graduate school in athletic counseling. She, too, takes after her father, who is an avid runner and coaches high school tennis.

Burke stresses that the career of his dreams began by taking initiative in college.

“I advise every college student to use your summers to get a head start,” he said.

He also encourages students to recognize the value in studying history. It’s about more than doing well in Jeopardy or trivia.

“History doesn’t have to be a direct track to teaching or law school, noble as those pursuits are. Employers across industries want analytical ability, clear writing, and the capacity to research complex topics — things in which history students are trained,” Burke said.

As a National Park Service historian, Burke experiences history as something alive and sensory, and this is how he hopes to represent it to guests.

“My goal is to present history as a fun and meaningful topic, not as drudgery and memorization.”

In short, he makes sure visitors leave Cape Cod National Seashore with history in their heads and sand in their shoes.