Student researchers discover the secrets of ant colony behavior

By Vicki-Ann Downing

In the research laboratory of Dr. James S. Waters, assistant professor of biology, students learn about natural history, physiology, and collective behavior by studying ants from the Providence College campus.

“The really cool thing about ants is that the colony is a self-organized system,” said Waters. “There are lots of individuals following simple rules, and no leaders, no hierarchy. All the individuals following simple rules make emergent patterns: division of labor, decision-making, nest architecture.

“We humans go to school to learn how to do these things. Little ants with even smaller brains spontaneously produce complex structures and patterns, and we’re trying to figure out how.”

When Waters joined the PC faculty in fall 2014, his first challenge was to build a collection of ants to study.

“We have to know what ants there are, who’s living with whom, and what are their interactions,” he said.

So Waters sent his students throughout campus to collect ants. They amassed 2,000 specimens and eventually identified 20 species, including a type of ant that should not have been present at all — the invasive Asian needle ant, native to China, Korea, and Japan, and recently prevalent in the central Atlantic states, but never before seen in New England.

The next step was to bring the colonies into the lab to begin studying their physiology and behavior.

Nicole Korzeniecki ’18 (Malba, N.Y.), who is majoring in biology and mathematics, is a student researcher in the Waters lab. She spent a summer as a researcher after being selected as a Walsh Student Research Fellow. Her job is to measure the metabolic rate of the colonies by determining how much oxygen they consume, how much carbon dioxide they produce, and the connection of both to the colony’s size and behavior.

“I’m excited to go and sit with these ants for hours at a time,” Korzeniecki said. “I planned to go to medical school, but now I realize that I love research — asking questions about the world around us, and trying to answer those questions by applying scientific methods.”

At an undergraduate liberal arts college like PC, becoming a researcher is easy, Waters said — a student need only ask.

“Anyone can get involved with research, and they don’t have to have any prior knowledge,” Waters said. “They can just say hi or send an email. We have lots of different projects. I find out what the students are interested in, and we go from there.”

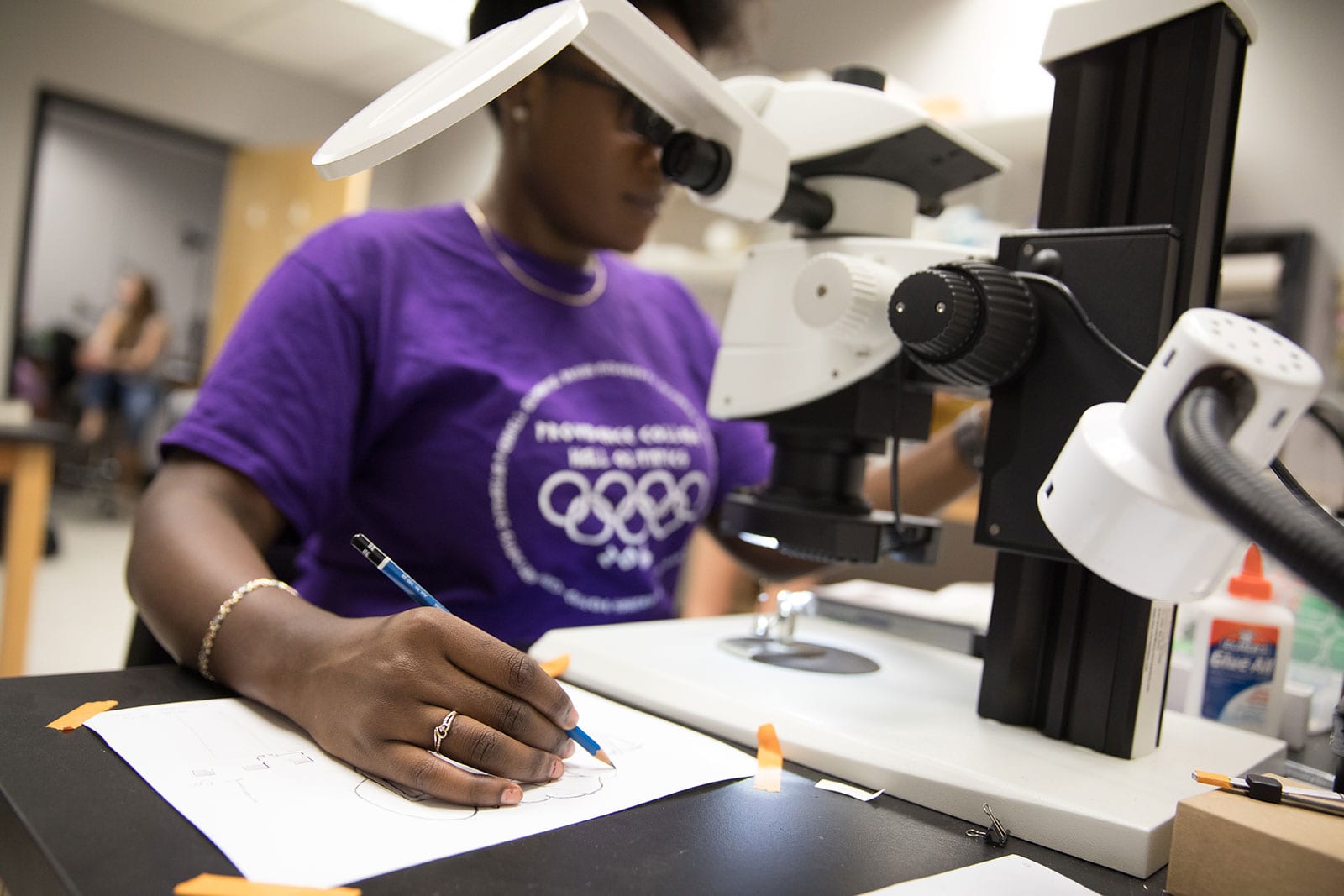

Aleyah Campbell ’19 (Springfield, Mass.), who is majoring in both biology and psychology, learned the art of scientific illustration in the Waters lab. Campbell used a microscope, artist’s pencils, and white paper to sketch every ant species collected by students from campus. Dr. Lynn M. Curtis, assistant professor of art, gave her a “crash course” in shading, lines, perspective, and how to play with light to highlight features.

A student could use a microscope and camera to photograph each ant species, but photography can be too detailed, said Waters. Scientific illustration allows the artist to highlight those features that make each ant species different from another.

“In order to draw something, you have to study it,” said Waters. “You observe the shapes, the curves, hairs, the spikes on the body.”

Campbell’s illustrations were scanned, digitized, and included in a scientific research paper that was presented by Waters and his students at the annual meeting of the Society for Integrative and Comparative Biology in New Orleans in January 2017.

Campbell, who is a resident assistant supervising sophomores, juniors, and seniors in Bedford and Davis halls, would like to be a physician’s assistant one day.

“Ants are very intelligent,” said Campbell. “It’s astonishing how intricate and detailed and goal-oriented they are. They are so good at communication. They even have hierarchies of social status. It’s incredible.”

Douglas Cassidy ’18 (Scotch Plains, N.J.), a biology major who hopes to attend medical school, said he has been impressed by the ability of ants to work collectively for the betterment of the colony. Student researchers have been able to use very small organisms to draw large conclusions about collective behavior, Cassidy said.

“By testing our hypothesis regarding mass scaling allometry, we are able to determine whether ants exhibit behavior with their metabolic rates that could potentially be reflected in various other species,” said Cassidy. “Dr. Waters has been a huge help through his style of teaching. He lets us conduct the research as he guides us. This is a very unique experience to have in an undergraduate setting, and I feel incredibly lucky to work alongside such a fantastic professor.”

Waters, a native of Queens, N.Y., studied mathematics at the University of Chicago. He did not develop an interest in biology until his senior year, when he took a required course in the natural sciences, on the topic of animal locomotion.

“I found out there were all these different questions,” said Waters. “I had no idea there were questions in biology. I thought it was all memorization.”

After graduation, he did a post-graduate year in insect research at the Field Museum in Chicago, then entered a Ph.D. program at Arizona State University, home of the world’s largest social insect research group — ants, bees, wasps, and termites — where ants became his research specialty. Just before joining the PC faculty, he spent two years as a postdoctoral research associate at Princeton University.

Ants are fascinating, Waters said. They are the most ecologically dominant group of animals on the planet. Their digging and colony-building aerate soils, which aids root growth. They keep herbivore populations in check — caterpillars and aphids that destroy crops. They decompose leaf litter. And their activity in the colony is a study in sociology.

“Ants don’t always agree,” said Waters. “It’s not always harmonious. They do police each other. There can be tension in the nest.”

Natural science is a liberal art, studied and taught by Albertus Magnus, the great Dominican teacher of the middle ages, Waters noted. In his study of insects, he is following in the footsteps of Rev. Charles V. Reichart, O.P. ’34, an entomologist and biology professor at PC for more than 50 years. When he died in 1997, Father Reichart’s collection of thousands of insects, gathered during his world travels, was donated to the Museum of Natural History at the Smithsonian Institution.

Waters would love to examine it one day.

“He may have collected ants in Rhode Island that are now in the Smithsonian,” said Waters. “It’s like a time capsule reveal.”