Providence College science research helps save the life of a woman in England

By Vicki-Ann Downing

A 17-year-old woman from England was cured of a life-threatening, drug-resistant infection after being treated with a virus scooped from the soil at Providence College, isolated and purified by students in a laboratory, and genetically modified by a professor on sabbatical.

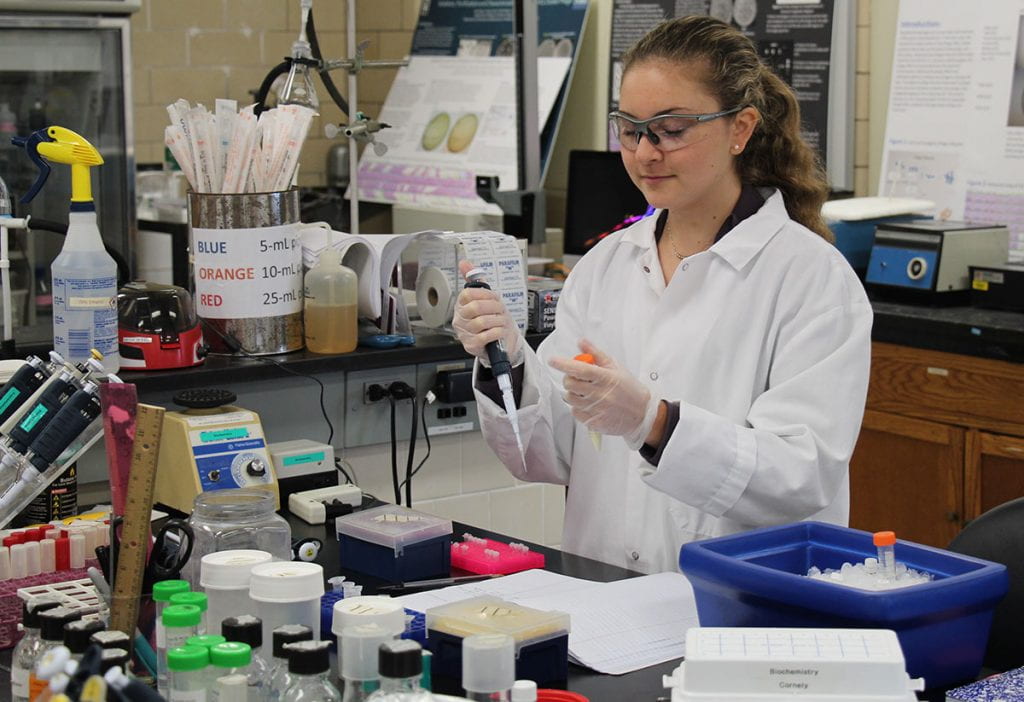

It was a worldwide medical breakthrough — the first successful use of a genetically modified virus to treat a drug-resistant infection — and was made possible, in part, by the work of Dr. Kathleen A. Cornely, professor of chemistry, and the students she co-taught in a class with Rev. Nicanor Austriaco, O.P., professor of biology and of theology.

“It was exciting to be part of this phage therapy project and wonderful to know that the patient is doing well,” Cornely said. “We offered the research course at PC in the hope that we might find a phage that could one day treat tuberculosis. To have success so quickly is just amazing.”

In late 2017, Isabelle Holdaway, who lives in Kent, England, and has cystic fibrosis, was dying from an infection after a double lung transplant. Her mother appealed to her doctor at Great Ormond Street Hospital in London to try an approach she read about on the internet — the use of phages, bacteria-killing viruses, to treat drug-resistant infections.

The physician turned to the University of Pittsburgh, where Dr. Graham Hatfull maintains a collection of 15,000 mycobacterial phages, the largest in the world — a collection that includes ZoeJ, a phage collected from soil under a tree near Harkins Hall in September 2012 by R. Seth Pinches ’16.

Pinches was one of 16 biology and biochemistry students in a Phage Hunters course co-taught by Cornely and Father Austriaco through PC’s membership in the Science Education Alliance, a partnership between the Howard Hughes Medical Institute and the University of Pittsburgh. More than 100 colleges and universities have taken part in SEA-PHAGES, the Phage Hunters Advancing Genomic and Evolutionary Science project.

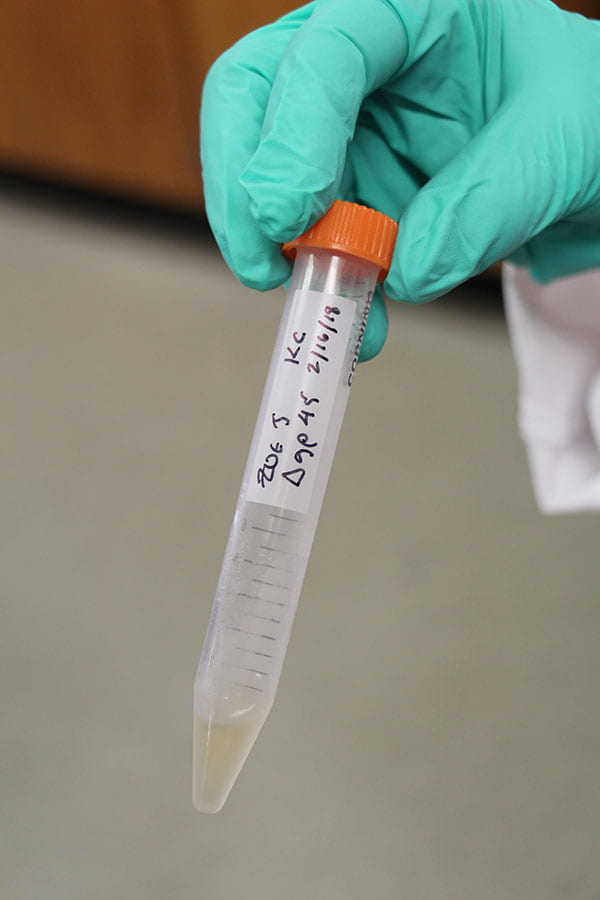

Through the course, students collected soil samples in vials and, in the laboratory, worked in teams to purify and characterize the phage and extract the DNA. Eventually, the class chose the phage with the highest quality DNA to send to the University of Pittsburgh for DNA sequencing and storage — ZoeJ, which Pinches named after his newborn niece, Zoe Jean.

The Phage Hunters course ended in May 2013, but Cornely continued the phage research with students in her lab during the academic year and in the summer. The students collected more phages but also studied ZoeJ, “a really interesting phage,” Cornely said.

Cornely was awarded a $25,000 grant from RI-INBRE, the Rhode Island IDeA Network for Biomedical Research Excellence, to support the work of her students, who also were supported by undergraduate research grants from the College and by Walsh Student Research Fellowships, created by a chemistry major, the late Robert H. Walsh ’39 & ’66Hon.

In January 2016, Cornely used a sabbatical semester to travel to Pittsburgh and work in Hatfull’s laboratory. With research associate Rebekah Dedrick, Cornely learned the technique of deleting a gene from ZoeJ that could prevent the phage from killing bacteria. It was a painstaking process that took her two months, working more than 60 hours a week, to accomplish.

“I was trying to bring my research to the next level,” Cornely said. “You can read about how to do the procedure, but there’s nothing like having someone in the lab showing it to you. It was a technique I wanted to teach my research students.”

When Cornely was finished, ZoeJ was a genetically modified phage ready to be used in treatment one day, if the need ever arose. Cornely left a sample of ZoeJ in a freezer in Pittsburgh and brought another back to Providence for her students to study.

In 2018, when Holdaway’s physician turned to the Hatfull lab, the team found 1,800 phages that matched the bacteria in her infection, including ZoeJ, a phage from Pittsburgh genetically modified in the Hartfull lab, and one from South Africa. The three were combined and administered intravenously and directly to the skin in June 2018.

Six weeks later, a liver scan showed the infection had disappeared. Today, Holdaway is 18 years old, studying for her college examinations, and learning to drive.

The news about the phage treatment received worldwide attention when it was reported in the journal Nature Medicine in May. Brianna Abbott ’17, who majored in chemistry and creative writing at PC, wrote about it in The Wall Street Journal, where she is a health reporter.

“The effort points to a potential path for countering the growing threat of bacteria resistant to antibiotics,” Abbott wrote. “The success suggests promise for using engineered phages more broadly against antibiotic-resistant bacteria.”

Today, Pinches is a program coordinator in the Laboratory for Molecular Pediatric Pathology at Boston Children’s Hospital and is applying to medical schools. He remembers receiving an email invitation to join the Phage Hunters course the summer before he entered PC and accepting it because it was an introduction to science research.

“The whole story is kind of amazing,” said Pinches. “The chances of the phage I discovered being used in treatment are so minute it’s crazy to think about. I did exactly what everyone else in the class did. I just got lucky. Seeing the photo of this young woman who is now alive because of this therapy makes me truly thankful for what science can do. I was just a very small part of the process, but I am happy to be that small part.”